I used to refuse to eat New Orleans food outside of New Orleans.

I left the city for Denver in 2002. One night, in my new hometown, I got in a fight with a chef when I told him I wouldn’t eat New Orleans food in Colorado. Sure, other restaurants could buy Gulf shrimp or oysters, and many did. But to me, the dishes from my former home represented not just themselves, but a whole culture.

After Katrina, which I watched white-knuckled from South Carolina, the New Orleans culture that was so tight and so insular – why would we need anyone else? – went into exile, diaspora, spread across the US. Brass bands were suddenly playing the classics in Utah and Montana, and I like to imagine the food went with them.

Let Truthout send our best stories to your inbox every day, for free.

Katrina, after all, was a natural disaster turned man-made disaster that mostly affected people. It ruined a city that had already ruined the wetlands surrounding it, but the music and the food that made the city so loved were still there. New Orleanians may have been forced to scatter around the country, but that also meant more people could discover – and come to love – what they had to offer.

Now, the disaster that has hit is entirely man-made, and it’s out in the Gulf – and staying. The BP spill is spreading, getting slowly worse every day since April 20, when an explosion on a rig started the leak that is pumping what some estimate could be 2.5 million gallons of oil a day into the water.

On land, away from the beaches, it’s possible to go on with life normally; despite the spill, the power works, gas is available, food is fresh and refrigerated. Yet, in Louisiana, in New Orleans, across the coast, there’s something missing.

John Martin Taylor wrote in The Washington Post:

The festive mood of Friday lunch at Galatoire’s did not seem changed since the first time I ate at the 105-year-old New Orleans institution in the late 1950s: the ladies resplendent in their hats and finery, the gents in their seersucker suits, the gin and bourbon flowing like water. The merriment belied the tragic reality of the day’s headline: P&J, the city’s 134-year-old oyster company, had stopped shucking that morning.

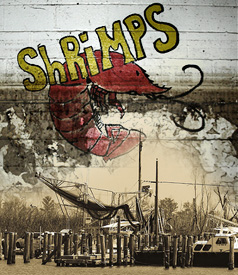

It may not seem like the biggest tragedy – not when we can see the pictures of oiled birds fighting to live and hear the stories of relief workers struggling to breathe after a day soaked in oil. But food from the Gulf is something that Gulf communities have always been able to count on. Hurricanes come and go, and the damage they leave behind on land may last for years (five since Katrina and Rita). But the fisherpeople were always able to go back out and resume their work, and the restaurants that were able to reopen could serve Gulf oysters and shrimp and fresh fish of the day to the tourists who pay the bills.

New Orleans – and the entire Gulf Coast – subsist on tourist dollars. Charter boats as well as commercial fishing boats have been sidelined by the oil slicking the waters and coating the beaches, and the money that BP is paying to a few of the workers from the boats isn’t enough to keep them going. Meanwhile, the Obama administration seems to be willing to let BP maintain a stranglehold not only on the cleanup process, but also on decision making about who gets to help.

We’ve already seen the first casualty of the despondency created among the people who depend on a clean Gulf for their living. William Allen Kruse, captain of a charter boat hired to help the cleanup, has committed suicide, and he may well not be the last person to abandon hope for the future.

The Los Angeles Times spoke to fishermen from the Gulf about the oncoming mental health crisis. Adam Trahan told them:

“I look out there and I see my life ruined,” Trahan, 53, said in his long Cajun drawl from the oceanside deck at Artie’s. “There ain’t no shrimpin’, there ain’t no crabbin’, there ain’t no oysterin’. Well, the only thing I know is shrimpin’. That’s all I know. Now you tell me: Where do I go from here? It’s heartbreakin’, baby.”

After Katrina and Rita, the Gulf Coast reeled – and much-needed mental health facilities closed, certainly not to be reopened under Louisiana’s Republican Gov. Bobby Jindal. New Orleans and the rest of the coast have always depended on music and food not just to draw tourists, who will no doubt be staying away now, but to maintain the culture, the community. The seafood that was, until now, exported across the country, was at its best cooked at home, miles or even just yards from where it was caught – and people traveled from across the world to eat it.

The music may still be playing in New Orleans’ bars, and the restaurants still serve red beans and rice. But the missing oysters and shrimp, whether in pricey Galatoire’s sauces or simply on po’ boys with gravy, must be an all too sharp and painful reminder of the mess just a few miles away – and of a government that is once again failing the people it promised to protect.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.