Rampant poverty and unemployment. Looming environmental crisis. Social and political upheaval. An emboldened al-Qaeda presence. Corrupt in-country partners. An ill-equipped, though increasingly active, United States.

No, Yemen is not Afghanistan. Nor will it be, despite careless intimations otherwise. But as this once unfamiliar country on the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula continues to ascend the list of US security concerns, greater engagement in the Republic of Yemen is both essential and fraught with peril.

Two recent announcements underscore the United States’ deepened commitment to Yemen and the considerable challenges this will entail. In June, the Senate Armed Services Committee passed the most recent defense appropriations bill (S.3454), which would allocate $75 million to building the capacity of Yemen’s counterterrorism forces. Meanwhile, later that month, President Obama increased US humanitarian assistance to Yemen by $29.6 million, for a total of $42.5 million in fiscal year (FY) 2010. While these amounts may represent mere pennies compared to US spending elsewhere – including daily expenditures of $200 million in Afghanistan, $175 million in Iraq and nearly $8 million in Israel – they have turned heads nonetheless as the latest examples of a much broader American investment in Yemen.

Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. (Photo: James R. King)

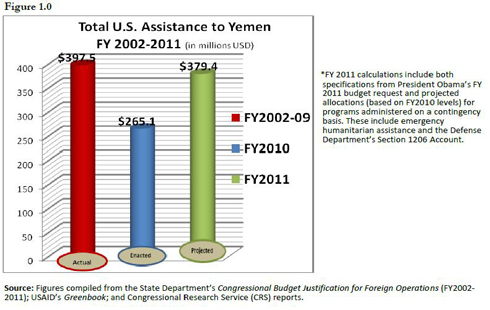

Largely neglected by the Bush administration, Yemen has become a key priority for the Obama administration. The most obvious manifestation of this shift is US aid to the country, which has risen dramatically since FY 2009. Between the FYs 2002-2009, the sum total of American assistance to Yemen fell short of $400 million. Conversely, President Obama’s FY 2010 enacted budget alone exceeds $250 million, and a reasonable projection for FY 2011 would easily top $300 million.

See Figure 1.0 below for a comparison of US assistance to Yemen between FY 2002 and FY 2011.

Though long overdue, sustained American attention to Yemen will be productive only if properly aimed. Yet, as in all of our national security hot spots, the difficulties in ensuring that our diplomatic, developmental and defense efforts can effectively bring security and stability are great.

Entering the “Perfect Storm” That Is Yemen

Yemen is confronting a “perfect storm” of problems. The government of Ali Abdullah Saleh (president, Yemen Arab Republic: 1978-1990; president, Republic of Yemen: 1990-) faces a trio of complex internal security challenges: a financially and legitimacy draining conflict in the Sa’dah region of northern Yemen, a secessionist movement in the formerly independent South and an increasingly confrontational al-Qaeda affiliate (al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, or AQAP). Meanwhile, Yemen’s socioeconomic and environmental crises are astounding, exacerbated by the presence of 350,000 internally displaced peoples (IDPs) in the north and the monthly influx of thousands of refugees from the Horn of Africa. A partial list includes:

- Food insecurity: Yemen is considered the world’s 11th most food insecure nation. One-third of its population suffers from acute hunger and half of its children are malnourished.

- Water shortages: Yemen’s water share/capita is 120 cubic meters, a meager 2 percent of the global average and 88 percent below the water poverty line. Some experts have predicted that Sana’a will literally run out of water by 2020.

- Poverty: Almost half of Yemen’s population lives on less than $2 a day, and unemployment rates, estimated as high as 35 percent, continue to spiral.

- Population growth: With one of the highest rates in the world at 3.5 percent annually, Yemen’s current population of 23 million to 24 million (nearly half under the age of 15) will likely double by 2030.

- Depleted oil reserves: Oil accounts for roughly 75 percent of Yemen’s state revenue. Declining production (23 percent decrease from 2006 to 2009) and low prices have created major budget deficits, and experts predict that, by 2017, state revenue from oil will be nil.

The challenges facing the United States in Yemen are enormous and unparalleled. In this context, even to confront them with a willing and capable Yemeni partner would be formidable. Yet, the Saleh regime appears neither willing nor capable.

Therefore, as we enter an unprecedented era in US-Yemen relations – one of higher stakes, amplified public scrutiny and copious aid packages – the Obama administration must take seriously these sobering realities and respond with judicious urgency.

As I have argued elsewhere, there is no panacea or silver bullet solution for Yemen. Instead, achieving stability – and ultimately, prosperity – will require years of sustained effort amongst the country’s internal and external stakeholders. The US certainly has a role to play, but in order to facilitate, rather than hinder, this process, the Obama administration must discard the stale foreign policy clichés that have been applied in such contexts as Afghanistan, Pakistan and Egypt. While habitual within Washington’s bureaucratic policy circles and easily digestible to a concerned (yet only marginally better educated on Yemen) American public, these policy “security blankets” will guarantee failure in the long run.

Below are four critical – and interconnected – ways that the administration, working with Congress, can avoid these futile approaches in Yemen. Central to this strategy is adopting a holistic and comprehensive policy framework that can effectively challenge AQAP’s widely resonant narrative in Yemen today. Each of these recommendations aims to prevent the reinforcement of that narrative and the resulting catalyzing of al-Qaeda recruitment, a scenario we have already witnessed in Afghanistan and Iraq as an unintended consequence of American blunders.

Don’t Underestimate the Divergent Priorities of Our Partner on the Ground

Click here to get Truthout stories like this one sent straight to your inbox, 365 days a year.

With the promise of nearly $175 million in security assistance this year, the Yemeni president has apparently assured the Obama administration of his regime’s capacity and will to fight al-Qaeda. Nevertheless, in spite of recent progress, our partner in Sana’a remains ineffective and unprepared at best, obstinate and defiant at worst. In fact, former US Ambassador to North Yemen William A. Rough recently described the government of Yemen’s cooperation in counterterrorism operations as “uneven,” asserting that “certain responses have caused US officials to regard Yemen as unreliable and obstructionist.”

Fostering a constructive relationship with Saleh demands an ability to discern how the Yemeni leader views his own political landscape: as a series of threats to his rule. Within this context, AQAP remains a remote third on his list of priorities behind the Southern Movement and the Houthis. Although the Obama administration has convinced the Saleh regime to prioritize security operations against AQAP, American interests will always take a back seat to these more existential threats. In other words, President Obama cannot assume Saleh’s a priori commitment to combating extremism, as opposed to his expedient and likely fleeting interest in doing so. Survival at any cost is the Yemeni resident’s great skill, and he has relied on extremist elements to either confront or placate rivals in the past. Saleh likes to equate ruling Yemen to “dancing with snakes.” The United States is just another snake, and he will manipulate this relationship to his advantage.

Consequently, the Obama administration must press its Yemeni partner to implement US security assistance in a manner consonant with American interests. For instance, it must demand built-in assurances that this aid is not swallowed up by corruption, or worse, used to wage the Houthi war or suppress dissent in the South, neither of which aligns with US strategic objectives in Yemen. This issue has arisen in connection with the proposed assistance to Yemen’s counterterrorism forces. Without delving too deep into budget technicalities, this $75 million is drawn from the Defense Department’s Section 1206 Account, which is designed for equipping and training foreign militaries. Yet, in an unprecedented move, this particular allocation has been stipulated to the Counter Terrorism Unit of Yemen’s Interior Ministry to conduct operations against AQAP. Although this paramilitary unit is better equipped to fight AQAP, by supporting these security forces, we risk abetting Saleh’s other internal security campaigns. The Senate Armed Services Committee identified this risk in the bill: “The committee notes that there have been public reports suggesting that the Government of Yemen may have used equipment provided by the United States to conduct operations against government opposition elements in both the North and South.” The problem was also recognized in a Senate Foreign Relations Committee report, which asserted that the Yemeni government was “likely diverting US counter-terrorism assistance for use in the war against the Houthis, and that temptation will persist.”

Don’t Support a Strong Man Leader to Repel the Terrorist Threat, While Ignoring the Core Grievances Against His Rule

Surely, the example of Afghanistan has taught us this lesson: citizens’ buy in to their country’s development trajectory is essential to achieving lasting security. The inability of the US government to convince Afghan President Hamid Karzai to address such issues as corruption, nepotism and incompetence continue to provide an ever-flowing well of legitimacy to our enemies in Afghanistan.

Likewise, Ali Abdullah Saleh represents a “dangerous friend.” With his regime’s history of exploiting Yemen’s regional and ideological differences, its rampant corruption and failure to provide basic services, as well as its cozy relationship with the United States, many Yemenis are disaffected with Saleh. The benefits are reaped by AQAP, which Alistair Harris rightly describes as “adept at aligning the grievances of Yemeni communities with its own narrative of what is right and who is responsible.” In fact, the Houthis, Southern Movement and AQAP are all products of this mounting frustration. Despite embodying very different objectives, ideologies and historical narratives, each of these groups has emerged within Yemen’s broader environment of political alienation and extreme economic hardship. For al-Qaeda in particular, the failure to translate this broad discontent into larger numbers of recruits (AQAP’s membership is estimated between several hundred and several thousand) is owed to the unpopularity of its methods of violent and largely indiscriminate jihad.

Yet, AQAP’s relatively small size is not assured moving forward, and the Obama administration must support both deradicalization and pre-emptive counterradicalization measures in Yemen. It must exhort the Saleh regime to pursue sweeping political and economic reform, in addition to directly repelling the terrorist threat. But with national elections approaching in 2013 and Saleh pledging not to run, it must also nurture a broader governance structure that is more responsive and representative of diverse Yemen’s regional, tribal and religious interests. In other words, whereas President Saleh is relied on to contain AQAP at present, a long-term and comprehensive strategy to eradicate al-Qaeda in Yemen must prepare for a post-Saleh world that eliminates the organization’s basic raison d’être.

Don’t Disconnect the Different Arms of US Policy

Forgetting the challenge of navigating relations with the Saleh regime, even counterterrorism operations are a precarious undertaking. This is well documented in Afghanistan, where civilian casualties have severely intensified insurgent violence. According to a recent National Bureau of Economic Research report: “Matching districts with similar past trends in violence shows that counterinsurgent-generated civilian casualties from a typical incident are responsible for 6 additional violent incidents in an average sized district in the following 6 weeks … if counterinsurgent forces in Afghanistan wish to minimize insurgent recruitment, they must minimize harm to civilians despite the greater risk this entails.”

Of course, the situation in Yemen is very different from Afghanistan. But while the morality and long-term efficacy of drone attacks and high-value targeting (HVT) campaigns must be debated more generally, the damning impact of dead or injured civilians on a local population’s attitude anywhere is indisputable. The United States is fighting a propaganda war in Yemen, and so-called “collateral damage” is a generous gift to AQAP, whose very survival depends on the pull of its narrative of Yemeni (and Arab-Muslim) suffering at the hands of American bullies and their local accomplices. This is a classic illustration of our paradoxical role in Yemen and the broader Middle East. When will we learn that our undeniably helpful interventions – and there are many – will always be overshadowed by our more controversial or nefarious ones? We hand out food with one hand and strike with the other.

The Obama administration must approach counterterrorism in Yemen cautiously. First, it must seek Congressional approval for any American military involvement. Executive war making, ostensibly justified under the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force Against Terrorists (AUMF) resolution, not only erodes government accountability in this country, but it will enflame the situation in Yemen as well. US policy in Yemen must be subject to a robust process of Congressional approval and oversight, a process that has continued to erode in places like Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The option of launching air strikes in Yemen, as the Bush administration did in 2002 to assassinate Abu Ali al-Harithi and which President Obama has authorized to target the American-Yemeni cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, should immediately come off the table. Nothing will better serve the AQAP propaganda machine than American military meddling in Yemen. Furthermore, in supporting the Yemeni government’s capacity to conduct security operations, the US government must ensure that these are aimed at known al-Qaeda operatives and avoid civilian casualties. In short, President Obama and the US government more broadly must eschew a “silo-ization” of American policy, recognizing that a single act (including outside of Yemen) can undo the positive impact of years of development and diplomacy work. This “shoot-ourselves-in-the-foot” foreign policy will only increase anti-American sentiment in Yemen and ultimately, drive Yemenis to al-Qaeda, rather than mobilizing them to uproot the organization.

Don’t Neglect Development and Humanitarian Assistance

The acute link between such environmental and structural problems as food insecurity or poverty and national security issues like instability, war and terrorism have long been recognized by experts and international instruments alike. In American foreign policy, too, the commitment to containing potential national security threats through anti-poverty and hunger reduction measures is hardly controversial. Such programs enjoy a rich history, from the Marshall/European Recovery Plan, to President Eisenhower’s Agricultural Trade Development Assistance Act (renamed Food for Peace), to Obama’s Feed the Future initiative. Without doubt, when people are hungry and destitute, they are more likely to turn to violence of any variety, whether crime, warfare or terrorist activities.

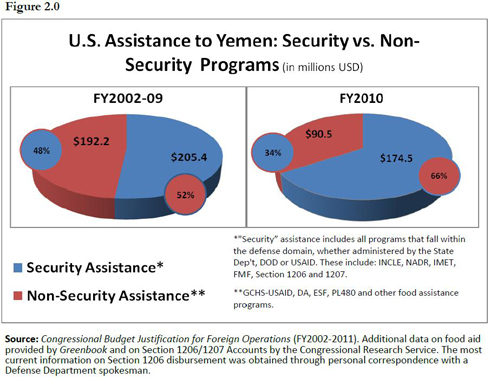

Nevertheless, US assistance to Yemen is disproportionately defense-oriented and increasingly so. See Figure 2.0 below for a comparison of American security and nonsecurity assistance between the fiscal years 2002-2009 and 2010.

Between FY 2002 and 2009, less than 52 percent of Yemen’s overall aid package was allocated to security over nonsecurity programs. President Obama’s FY 2010 enacted budget, on the other hand, prioritizes security assistance to the tune of 66 percent, allocating over $174 million to security programs, compared to $90 million in nonsecurity programs. Although the substantial increase in humanitarian and development aid is laudable – the FY 2010 budget allocates nearly 150 percent more nonsecurity aid than does FY 2009 for example ($90 million versus $36 million) – the even sharper bulge in security assistance underscores the need for a paradigm shift in how the US seeks to promote security and stability in Yemen.

The Obama administration must approach Yemen holistically. Working with Congress, it must address both Yemen’s immediate security threats related to al-Qaeda and those “nonsecurity” issues that demand humanitarian and development interventions. To neglect the latter will only guarantee the continued existence of the former. As Yemen expert Gregory Johnsen has argued, “By focusing on al-Qaeda to the exclusion of nearly every other threat and by linking most of its aid to this single issue, the United States has ensured that it will always exist.”

Can We Weather the “Perfect Storm”?

Clearly, the United States faces a serious and multifaceted challenge in the Republic of Yemen. And the Obama administration has responded by making legitimate progress in articulating a more holistic and comprehensive foreign policy approach. Unlike its antecedents, Obama’s Yemen policy attempts to creatively combine political reform, humanitarian assistance and counterterrorism operations through enhanced coordination and cooperation across departments and agencies. Yet, in the overall analysis, President Obama has not escaped falling into that proverbial foreign policy trap in Yemen. His security-dominated approach continues to prioritize counterterrorism over human development (where Yemen ranks 140th out of 182 countries), and, for the most part, it has granted the Yemeni president a dangerous free hand within Yemen in exchange for cooperation on security operations.

This stopgap approach may yield temporary results, but ultimately, it risks nurturing more permanent disasters. The greatest security danger in Yemen lies in the continued political alienation, physical hardship and sense of despair that threatens to push Yemenis toward extremism. This explosive combination cannot be addressed on the battlefield through counterterrorism operations. Rather, it is the nexus of Yemen’s core systemic crises – political, socioeconomic and environmental – where al-Qaeda will be defeated.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.