Part of the Series

The Public Intellectual

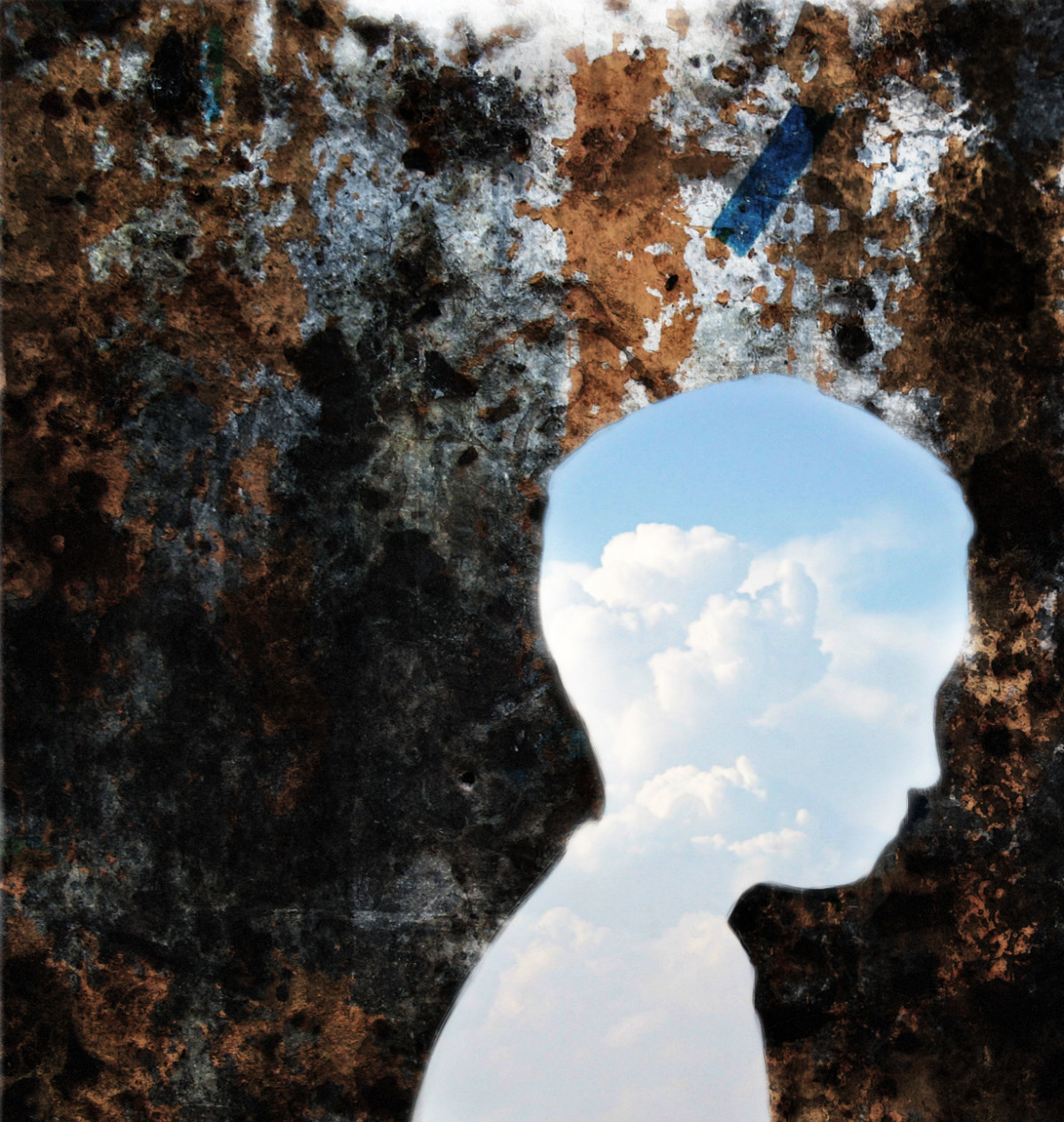

Any rigorous conception of youth must take into account the inescapable intersection of the personal, social, political and pedagogical embodied by young people. Beneath the abstract codifying of youth around the discourses of law, medicine, psychology, employment, education and marketing statistics, there is the lived experience of being young. For me, youth invokes a repository of memories fueled by my own journey through an adult world, which largely seemed to be in the way, a world held together by a web of disciplinary practices and restrictions that appeared at the time more oppressive than liberating. Lacking the security of a middle-class childhood, my friends and I seemed suspended in a society that neither accorded us a voice nor guaranteed economic independence. Identity didn’t come easy in my neighborhood. It was painfully clear to all of us that our identities were constructed out of daily battles waged around masculinity, the ability to mediate a terrain fraught with violence and the need to find an anchor through which to negotiate a culture in which life was fast and short-lived. I grew up amid the motion and force of mostly working-class male bodies – bodies asserting their physical strength as one of the few resources over which we had control.

Dreams for the youth of my Smith Hill neighborhood in Providence, Rhode Island, were contained within a limited number of sites, all of which occupied an outlaw status in the adult world: the inner-city basketball court located in a housing project, which promised danger and fierce competition; the streets on which adults and youth collided as the police and parole officers harassed us endlessly; the New York system, hole-in-the-wall restaurant operated by a guy who always had ten “hot dogs” and buns in various stages of preparation on his arm on a Saturday night and would wait for us to do business after we spent a night hanging out, drinking and dancing.

For many of the working-class youth in my neighborhood, the basketball court was one of the few public spheres in which the kind of cultural capital we recognized and took seriously could be exchanged for respect and admiration. If you weren’t good enough, you didn’t play; if you were good, you performed with a kind of humility arbitrated by a code that suggested you didn’t lose easily. Nobody was born with innate talent. Nor was anybody given instant recognition. The basketball court became for me a rite of passage and a powerful referent for developing a sense of possibility. We played day and night and we played in any space that was available. Even when we got caught breaking into St. Patrick’s Elementary School one Friday night around 1:00 AM, the cops who found us knew we were there to play basketball rather than to steal money from the teachers’ rooms or Coke machines. Basketball was taken very seriously because it was a neighborhood sport, a terrain where respect was earned. It offered us a mode of resistance, if not a respite, from the lure of drug dealing, the sport of everyday violence and the general misery that surrounded us. The basketball court provided another kind of hope, one that seemed to fly in the face of the need for high status, school credentials or the security of a boring job. It was also a sphere where we learned about the value of friendship, solidarity and respect for the other.

Yet, the promise of the basketball court evaporated when high school ended and all but a talented few of the young men in the neighborhood moved from school to any one of a number of dead-end jobs or public service jobs that offered a more promising future. The best opportunities came from taking a civil service test and, if one were lucky, one got a job as a policeman or fireman (as James Brown reminded us, it was strictly a “man’s world” then). Job or no job, one forever felt the primacy of the body: the body flying through the rarefied air of the neighborhood gym in a kind of sleek and stylized performance; the body furtive and cool existing on the margins of society filled with the possibility of instant pleasure and relief, or tense and anticipating the danger and risk; the body bent by the weight of grueling labor.

The body, with its fugitive status within working-class culture, allowed boys like myself from white, working-class neighborhoods to cross racial borders and rewrite the endemic racism of our community. We were white boys, and race and class positioned our bodies in turf wars marked by street codes that were both feared and respected. At the age of eight, I became a shoeshine boy and staked out a route inhabited by black and white nightclubs in Providence, Rhode Island. On Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights, I started my route about 7:00 PM and got home around 12:00 AM. I loved going into the Celebrity Club and other bars, watching the adults dance, drink and steal furtive glances from each other. Most of all, I loved the music. Billie Holiday, Fats Domino, Dinah Washington, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers and Little Richard played in the background against the sounds of glasses clinking and men and women talking – talking as if their only chance to come alive was compressed into the time they spent in the club. Whenever I finished my route, I had to navigate a dangerous set of streets to get back home. I learned how to talk, negotiate and defend myself along that route. I was too skinny as a kid to be a tough guy; I had to learn a street code that was funny but smart, fast but not insulting. That’s when my body and head started working together. While I didn’t realize it at the time, I was learning fast that the working of the intellect was as powerful a weapon as the body itself. In spite of what I learned in that neighborhood about the virtues of a kind of militant masculinity, I had to forge a different understanding about the relationship between my body and mind – one in which the body was only one resource for surviving.

I saw a lot in that neighborhood and I couldn’t seem to learn enough to make sense of it or escape its pull. Peer groups formed early and kids ruptured all but the most necessary forms of dependence on their parents at a very young age. I really only saw my parents when I went home to eat or sleep. All of the youth left home too early to notice the loss until later in life when we became adults or parents ourselves. Leaving home for me was made all the more complicated because my mother had severe epilepsy and had repeated seizures. My sister and I were not distant observers to my mother’s suffering – we often had to hold her down in bed when the seizures erupted. Shuffled between hospitals and institutions, my mother wasn’t home much. As a result of my mother’s absence, my sister was taken away by the social services and placed in a Catholic residence for girls. Losing my sister to an orphanage, I experienced for the first time what it meant to be homeless in my own home. Home was neither a source of comfort nor a respite from the outside world. The neighborhood was my real home and my friends provided the sanctuary for talk and security along with a cool indifference to the fact that none of us looked forward to the future. When I was in high school, I remember visiting my mother in state hospitals and being alarmed by the fact that many of the attendants were guys from my neighborhood, guys who seemed dangerous and utterly indifferent to human life, guys whom on the streets I had both known and avoided. It seemed to me like everybody was warehoused in that neighborhood, irrespective of age.

I eventually left my neighborhood, but it was nothing less than a historical accident that allowed me to leave. I never took the requisite tests to apply to a four-year college. When high school graduation came around, I was offered a basketball scholarship to a junior college in Worcester, Massachusetts. It seemed better to me than working in a factory, so I went off to school with few expectations and no plans except to play ball. I was placed in a business program, but had no interest in what the program offered. The culture of the college seemed terribly alien to me and I missed my old neighborhood. After violating too many rules and drinking more than I should have, I saw clearly that my life had reached an impasse. I left school and went back to my old neighborhood hangouts.

My friends’ lives had already changed. Their youth had left them and they now had families and lousy jobs and spent a lot of time in the neighborhood bar waiting for a quick hit at the racetrack or the promise of a good disability scheme. After working for two years at odd jobs, I managed to play in the widely publicized Fall River basketball tournament and did well enough to attract the attention of a few coaches who tried to recruit me. Following their advice, I took the SATs and scored high enough to qualify for entrance into a small college in Maine that offered me a basketball scholarship. But nothing came easy for me when it came to school. Although I made the starting lineup on the varsity team and managed to be the team high scorer my freshman year, the coach resented me because I was an urban kid – too flashy, too hip and maybe too dangerous for the rural town of Gorham, Maine. I left the team at the beginning of my sophomore year, took on a couple of jobs to finance my education and eventually graduated with a teaching degree in secondary education.

After getting my teaching certificate, I became a community organizer and a high school teacher. Then, worn thin after six years of teaching high school social studies, I applied for and received another scholarship, this one to attend Carnegie-Mellon University. I finished my course work early and spent a year unemployed while writing my dissertation. I finally got a job at Boston University. Again, politics and culture worked their strange magic as I taught, published and prepared for tenure. My tenure experience changed my perception of liberalism forever. Like many idealistic young academics, I believed that if I worked hard at teaching and publishing I would surely get tenure. I did my best to follow the rules, but did so with little understanding of the political forces governing Boston University at that time. It turned out I was dead wrong about the rules and the alleged integrity of the tenure process.

By the time I came up for tenure review, I had published two books and 50 journal articles and given numerous talks and I went through the tenure process unanimously at every level of the university. But then, unexpectedly, I was denied tenure by John Silber, president of Boston University, who not only ignored the various unanimous tenure committee recommendations, but actually solicited letters supporting denial of my tenure from notable conservatives such as Nathan Glazer and Chester Finn. Glazer’s review was embarrassing in that it began with the comment, “I have read all of the work of Robert Giroux.” The dean of education, my supporter, threatened to resign if I did not receive tenure. Of course, he didn’t. Silber’s actions had a chilling effect on many faculty who had initially rallied to my support. They realized quickly that the tenure process was a rigged affair under the Silber regime and that anyone who complained about it might compromise their own academic career. One faculty member apologized to me for his refusal to meet with Silber to protest my tenure decision. Arguing that he owned two condos in the city, he explained that he couldn’t afford to act on his conscience since he would be risking his investments. Of course, his conscience went on vacation when it came to acting in defense of his material assets.

By the time I met Silber to discuss my case, I was convinced that my fate had already been decided. Silber met me in his office, asked me why I wrote such “shit,” and made me an offer. He suggested that if I studied the philosophy of science and logic with him as my personal tutor, I could maintain my current salary and would be reconsidered for tenure in two years. The only other catch was that I had to agree not to write or publish anything during that time. I was taken aback and responded with a joke by asking him if he wanted to turn me into George Will. He missed the humor and I left. I declined the offer, was denied tenure and after sending off numerous job applications finally landed a job at Miami University. Working-class intellectuals do not fare well in the culture of higher education, especially when they are on the left of the political spectrum. I have been asked many times since this incident whether I would have continued the critical writing that has marked my career if I had known that I was going to be fired because of the ideological orientation of my work. Needless to say, for me, it is better to live standing up than on one’s knees. Sadly, my story of being denied tenure at Boston University – at the time an aberration from the norm – is now becoming all too familiar tale. Today, academics have become another group suffering from the threat of exclusion and disposability as their autonomy is increasingly questioned and constrained by business-oriented administrators.

In my early career at the university, the academic game seemed rigged against me, but even then I had become more of an exception than the rule. The lesson here is that whether we are talking about failure or success surely the experiences of many working-class kids in this culture are more an effect of their place in society than the result of either personal inadequacy, on the one hand, or an unswerving commitment to the ethic of hard work and individual responsibility, on the other.

My youth was lived through class formations that I felt were largely viewed by others as an outlaw culture. Schools, hospitals, community centers and surely middle-class social spaces interpreted us as alien, other and deviant because we were from the wrong class and had the wrong kind of cultural capital. As working-class youth, we were defined through our deficits. Class marked us as poor, inferior, linguistically inadequate and often dangerous. Our bodies were more valued than our minds and the only way to survive was to deny one’s voice, experience and location as working-class youth. We were feared and denigrated more than we were affirmed, and the reality of being part of an outlaw culture penetrated us with an awareness that we could hardly navigate critically or theoretically, but felt in every fiber of our being.

The working-class culture in which I grew up wore its fugitive status like a badge, but all too often it was unaware of the contradictions that gave it meaning. We lacked the political vocabulary and insight that would have enabled us to see the contradiction among the brutal racism, violence and sexism that marked our lives and our constant attempts to push against the grain by investing in the pleasures of body, the warmth of solidarity and the appropriation of neighborhood spaces as outlaw publics. As kids, we were border crossers and had to learn to negotiate the power, violence and cruelty of the dominant culture through our own lived histories, restricted languages and narrow cultural experiences. Recognizing our fugitive status in all of the dominant institutions in which we found ourselves – including schools, the workplace and social services – we were suspicious and sometimes vengeful of what we didn’t have or how we were left out of the representations that seemed to define American youth in the 1950s and early 1960s. We listened to Etta James and hated both the music of Pat Boone and the cultural capital that for us was synonymous with golf, tennis and prep schools. We lost ourselves in the grittiness of working-class neighborhood gyms, abandoned cars and street corners that offered a haven for escape, but also invited police surveillance and brutality. Being part of an outlaw culture meant that we lived almost exclusively on the margins of a life that was not of our choosing. And as for the present, it was all we had since it made no sense to invest in a future that for many of my friends either ended too early or pointed to the dreaded possibility of becoming an adult, which usually meant working in a boring job by day and hanging out in the local bar by night. We bore witness to the future only to escape into the present, and the present never stopped pulsating. Like most marginalized youth cultures, we were time bound. The memory work would have to come later. But when it came, it offered us a newfound appreciation of what we learned in those neighborhoods about solidarity, trust, friendship, sacrifice and, most of all, individual and collective struggle.

Bearing witness as I have tried to do is not simply a private rendering of biographical events. It is a mode of analysis that seeks to connect private troubles to larger social issues, just as it always implicates one in the past and gives rise to reflections on how youth act and are acted upon within a myriad of public sites, cultures and institutions. Some theorists have suggested that the practices of witnessing and testimony lie at the heart of what it means to teach and to learn. Witnessing and testimony, translated here, mean speaking and listening to the stories of others as part of both an ethical response to the narratives of the past and a broader responsibility to engage the present. I often wonder how my own formation as a working-class youth and eventual border crosser, moving often without an “official passport” among cultures, ideologies, jobs and fugitive knowledge, might be invoked as a form of bearing witness. How might the testimony I bear witness to help me not only to interrogate my own shifting location as a critical educator, but also provide an important narrative and locus for identification through which others can begin to understand the complexity and significance of the different conditions that have shaped our individual and collective histories? The message for educators and other cultural workers that emerges out of this interaction is the pedagogical challenge that “if teaching does not hit upon some sort of crisis, if it does not encounter either the vulnerability or the explosiveness of a[n] (explicit or implicit) critical and unpredictable dimension, it has perhaps not truly taught.”(1)

The crisis I speak of in this instance is about the plight of youth as a social and political category in an age of increasing symbolic, material and institutional violence. It is a crisis rooted in society’s loss of any sense of history, memory and ethical responsibility. The idea of the public good, the notion of connecting learning to social change, the idea of civic courage being infused by social justice, have been lost in an age of rabid consumerism, media-induced spectacles and short-term, high-yield financial investments. Under the regime of neoliberalism and a rigidly market-driven society, concepts and practices of community and solidarity have been replaced by a world of cutthroat survival, even as politics has become an extension of war. What youth learn quickly today is that their fate is solely a matter of individual survival, a natural law of sorts that has more to do with survival instinct than with modes of collective reasoning, social solidarity and the formation of a sustainable democratic society.

My youth may be marked as the last time when young people could still experience the hope and support given to poor youth in the form of a social state that took the social contract somewhat seriously. While we may have lived in private hells, we never felt entirely demonized or shut out from the most basic social services. Nor did we feel that our troubles were simply private issues. We hung out at the boys’ club, took part in after-school sports, joined summer leagues, had an opportunity to attend day camps and knew that even in the worst of times we could count on (in the present and in the future) medical support, a job and a wage, however unfair. Politicians at either end of the political spectrum viewed youth as a social investment, even if it meant investing in some youth more than in others. Responsibility provided both moral sustenance and presented occasions in which the practices of compassion, trust and respect mediated the relationship between the self and others. Authority was never beyond critique; resistance was a mark of pride; and the moral obligation to care for others was embodied in our personal codes, religious institutions and state-sponsored services. A respect for the common good prevailed. Community was a word, however flawed, that resonated with a deeply-felt concern for the public good and the public institutions that nourished it. Love, friendship, hard work, helping neighbors in distress and respect for the people one associated with thrived in that neighborhood where I grew up. Labels and logos did not define my generation. Commodity culture was outside of our reach and it was only later in life that I realized what a blessing that had been, particularly as neighborhoods organized around a different and more honest set of values in which the suffering and misfortunes of others were taken seriously.

What was striking about my Smith Hill neighborhood was the view that nobody was disposable and that giving and receiving collective support was a virtue, not a liability or sign of weakness. In the midst of poverty and various crisis situations, the entire working-class neighborhood often mobilized to provide food, clothing and in some cases money for distressed families and disadvantaged young people. The men and women in my neighborhood worked hard, shared their stories, gathered at church on Sundays and recognized injustice when they saw it. No one bought into the myth that individuals alone had to bear both the blame and the responsibility for their own survival in times of crisis. If the parents, young people and working-class adults I grew up with lacked power, they made up for it by working hard within the limits imposed on them in a society that produced vast amounts of inequality and brutality.

Youth in my neighborhood had a difficult time growing up. There were no innocent young people on those streets, just young people trying to act like adults in order to stay alive and get by. But in spite of how bad it was, there was a sense of civic values and a respect for the public good in which all of us believed. If youth were under siege, it was largely because of repressive forces that were imposed on us from alien and hostile sites of which we tried to stay clear. The police roamed our neighborhoods on foot patrols and, while often repressive and authoritarian, they were still absent from our schools. When we went to school, we didn’t have to face the disciplinary apparatus of an expanding criminal justice system that many young people face today with the ongoing development of militarized schools. We were disciplined in a much different manner. Guidance teachers were the masters of our fate and shamelessly determined how many of us poor kids should be in vocational classes because we were clearly incapable of being intelligent. But there were no police in my school, just adult authority figures and teachers who believed that the school was a public rather than a private good, however flawed their actions were at times. While many of us were tracked at Hope High School by administrators and teachers who felt we were more of a liability than an asset, there were also plenty of other adults around to offer guidance and help. They picked us up and gave us a ride to school on occasion, given the long hike and often inclement weather we had to face. They often lived in our neighborhoods and knew people in the community. They joked with us, understood the restricted code and watched out for those young people who were always on the verge of dropping out of high school.

In the 1950s and ’60s, the neoliberal world of vast inequalities and exclusions in which people are only connected to each other through the possibility of enhancing profit margins was only just beginning to rear its ugly values and institutional tentacles. Matters of agency and politics, however deformed, were still the subject and grounds for both criticism and hope. Collective responsibility for individual well-being was still alive, at least as an ideal in the America of my youth and it was precisely such an ideal that drove the civil rights movement, the student rebellions of the sixties and the Great Society policies under President Lyndon Johnson. Put another way, a democratic consciousness at that point in history had not been snuffed out by market-driven values and policies mobilized under the reign of a cruel and unjust neoliberalism, largely hatched among the elite at the University of Chicago and in the highest levels of government.(2) Privatized utopias and gated spaces were not part of our experience as young people growing up at that time. The consumerist utopia that would later descend like a plague on American society in the 1980s was still capable of being challenged and resisted in the search for more democratic and compassionate values and social relations.

For many poor, white youth and youth of color today, the notion of solidarity and the sense of dependence and respect that marked my childhood are gone. Instead, America today is waging not only an immoral and unjust war abroad in Iraq and Afghanistan, but also a more insidious high-intensity war at home against any viable notion of the social.(3) Social protections and investments, even as they apply to youth who are utterly dependent upon the larger society, are now the object of scorn as right-wing politicians – whom I call the new barbarians – demand the elimination of Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, unemployment benefits, and any other program aimed at helping those suffering from the systemic failures of an unjust and often cruel socioeconomic system. For many young people today, the possibility of a better future has vanished as one in seven Americans live in poverty and over 50 million are deprived of health insurance.(4) More and more children are growing up poor, facing a world with few job opportunities and viewed as being trouble rather than facing troubles. Food banks and prisons have become the new public spheres for young Americans who are poor and marginalized. As poverty reaches record levels, the number of children in poverty has risen to 15.5 million, and there is barely a peep of outrage heard from either politicians and intellectuals or the general public.

When the new barbarians suggest that young people get married in order to avoid poverty, the statement is analyzed by mainstream media and anti-public intellectuals less as a lapse into savagery than as a thoughtful policy suggestion.(5) Rather than call for policies that could keep young Americans out of poverty such as combating rising income inequality and providing more jobs and benefits for the growing multitude of disposable youth and adults, the right-wing barbarians talk about how the Obama administration is abusing the rich and powerful by refusing to extend the tax breaks given to them by George W. Bush. The new barbarians’ vitriolic outrage over the deficit and government spending is utterly hypocritical and ideologically transparent as they simultaneously argue for extending high-end tax breaks for the rich and powerful, a move that will deprive the government of over $700 billion in much needed revenue. Lost in their discourse is any attempt to reflect on failed right-wing policies that spawned the economic recession in the first place. And there is certainly little attempt on the part of conservative Republican and Democratic Party members to champion policies that might actually “expand the safety net, strengthen labor rights, build a more humane and efficient health care system, reward hard work with living wages and value society’s most vulnerable members, children.”(6)

The new culture of cruelty combines with the arrogance of the rich as morally bankrupt politicians such as Mike Huckabee tell his fellow Republican extremists that the provision in Obama’s health care bill that requires insurance companies to cover people with pre-existing conditions should be repealed because people who have these conditions are like houses that have already burned down. The metaphor is apt in a country that no longer has a language for compassion, justice and social responsibility. Huckabee at least is honest about one thing. He makes clear that the right-wing fringe leading the Republican Party is on a death march and has no trouble endorsing policies in which millions of people – in this case those afflicted by illness – can simply “dig their own graves and lie down in them.”(7) The politics of disposability ruthlessly puts money and profits ahead of human needs. Under the rubric of austerity, the new barbarians such as Huckabee now advocate eugenicist policies in which people who are considered weak, sick, disabled or suffering from debilitating health conditions are targeted to be weeded out, removed from the body politic and social safety nets that any decent society puts into place to ensure that everyone, but especially the most disadvantaged, can access decent health care and lead a life with dignity. Consequently, politics loses its democratic character along with any sense of responsibility and becomes part of a machinery of violence that mimics the fascistic policies of past authoritarian political parties that eagerly attempted to purify their societies by getting rid of those human beings considered weak and inferior and whom they ultimately viewed as human waste. I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that a lunatic fringe of a major political party is shamelessly mimicking and nourishing the barbaric roots of one of the most evil periods in human history. By arguing that individuals with pre-existing health conditions are like burned-down houses who do not deserve health insurance, Huckabee puts into place those forces and ideologies that allow the country to move closer to the end point of such logic by suggesting that such disposable populations do not deserve to live at all.

Welcome to the new era of disposability in which market-driven values peddle policies that promote massive amounts of human suffering and death for millions of human beings. Programs to help the elderly, middle aged and young people overcome poverty, get decent jobs, obtain access to health insurance and decent health care and exercise their dignity and rights as American citizens are denounced in the name of austerity measures that only apply to those who are not rich and powerful.(8) At the same time, the new disposability discourse expunges any sense of responsibility from both the body politic and the ever-expanding armies of well-paid, anti-public intellectuals and politicians who fill the air waves with poisonous lies, stupidity and ignorance, all in the name of so-called “common sense” and a pathological notion of freedom stripped of any concern for the lives and misfortunes of others. In the age of disposability, the dream of getting ahead has been replaced with, for many people, the struggle to simply stay alive. The logic of disposability and mean-spirited cruelty that now come out of the mouths of zombie-like politicians are more fitting for the authoritarian regimes that emerged in Russia and Germany in the 1930s rather than for any society that calls itself a democracy. A politics of uncertainty, insecurity, deregulation and fear now circulates throughout the country as those marginalized by class and color become bearers of unwanted memories, subject to state-sanctioned acts of violence and rough justice. Poor minority youth, immigrants and other disposable populations now become the flash point that collapses moral and political taxonomies in the face of a growing punishing state. Instead of becoming the last option, violence and punishment have become the standard response to confronting the problems of the poor, disadvantaged and jobless. As Judith Butler points out, those considered “other” and disposable are viewed as “neither alive nor dead, but interminable spectral human beings no longer regarded as human.(9) Thinking about visions of the good society is now considered a waste of time.

As Zygmunt Bauman points out, too many young people and adults

are now pushed and pulled to seek and find individual solutions to socially created problems and implement those solutions individually using individual skills and resources. This ideology proclaims the futility (indeed, counterproductivity) of solidarity: of joining forces and subordinating individual actions to a “common cause.” It derides the principle of communal responsibility for the well-being of its members, decrying it as a recipe for a debilitating “nanny state” and warning against care for the other leading to an abhorrent and detestable “dependency.”(10)

Tea Party candidates express anger over government programs, but say nothing about a government that provides tax breaks for the rich, allows politicians to be bought off by powerful lobbyists, contracts out government functions to private industries and guts almost every major public sphere necessary for sustaining an increasingly faltering democracy. Tea Party members are outraged, but their anger is really directed at the New Deal, the social state and all those others whom they believe do not qualify as “real” Americans.(11) At the same time the American public is awash in a craven and vacuous media machine that routinely tells us that people are angry, but offers no analysis capable of treating such anger as symptomatic of an economic system that creates massive inequalities, rewards the ultra rich and powerful and punishes everybody else.

Bob Herbert has recently argued that the rich and powerful are indifferent to poor people and, of course, he is right, but only partly so.(12) In actuality, it is much worse. Today’s young people and others caught in webs of poverty and despair face not only the indifference of the rich and powerful, but also the scorn of the very people charged with preserving, protecting and defending their rights. We now live in a country in which the government allows entire populations and groups to be perceived and treated as disposable, reduced to fodder for the neoliberal waste management industries created by a market-driven society in which gross inequalities and massive human suffering are its most obvious byproducts.(13) The anger among the American people is more than justified by the suffering many people are now experiencing, but an understanding of such anger is stifled largely by right-wing organizations and rich corporate zombies who want to preserve the nefarious conditions that produced such anger in the first place. The result is an egregious politics of disconnection, not to mention a fraudulent campaign of lies and innuendos funded by shadowy, ultra right billionaires such as the Koch brothers,(14) the loss of historical memory amply supported in dominant media such as Fox News and a massively funded depoliticizing cultural apparatus, all of which help to pave the way for the new barbarism and its increasing registers of cruelty, inequality, punishment and authoritarianism.

This is a politics that dare not speak its name – a politics wedded to inequity, exclusion and disposability and beholden to what Richard Hofstadter once called the “paranoid style in American politics.”(15) Driven largely by a handful of right-wing billionaires such as Rupert Murdoch, David and Charles Koch and Sal Russo, this is a stealth politics masquerading as a grassroots movement. Determined to maintain corporate power and the benefits it accrues for the few as a result of vast network of political, social and economic inequalities it reproduces among the many, this is a politics wedded at the hip to an irrational mode of capitalism that undermines any vestige of democracy. At the heart of the new barbarian politics is the drive for unchecked amounts of power and profits in spite of the fact that this brand of take-no-prisoners politics is largely responsible for both the economic recession and producing a society that is increasing becoming politically dysfunctional and ethically unhinged. It is a fringe politics whose funding sources hide in the shadows careful not to disclose the identities of the right-wing billionaire fanatics eager to finance ultra-conservative groups such as the Tea Party movement. While some Republicans seem embarrassed by the fact that the likes of Glenn Beck, Rush Limbaugh and Sarah Palin have taken over their party, most of its members still seem willing to embrace wholeheartedly the politics of inequality, exclusion and disposability that lies at the heart of an organized death-march aimed at destroying every public sphere essential to a vibrant democratic state.

The United States has not just lost its moral compass in a sea of collective anger; it has become a country that is no longer able to connect reason and freedom, recognize the anti-democratic forces that now threaten it from within and for the most part question its capacity to protect its citizens from the ravages of unscrupulous neoliberalism as its spreads like a plague across the globe. The spectacle of moral panics over immigrants, the wild fire of religious and racial bigotry, conscienceless support for unchecked inequality and corporate power, the endless reproduction of celebrity and consumer culture and the growing registers of shared fears now define American politics. The future is increasingly being shaped by barbarians who thrive on ignorance and stupidity, while reaping the rewards of big corporate power and money. Freedom is now tied to the making of instant fortunes largely by the corporate elite and to an individualistic ethic that disdains any notion of solidarity and social responsibility. The social state has become a garrison state committed to dismantling collective forms of insurance that cover individuals who suffer from debilitating and life-changing calamities while simultaneously expanding the human waste disposal industries.

What does it mean when a country denies basic social provisions to the young, poor, elderly and those suffering from tragedies and hardships that are not of their own making and which cannot be addressed through the call to individual responsibility? What happens when the war on poverty becomes the war on the poor? What does it mean when the political state cedes its power to corporate power? Where is America going when it turns its back on its own children, condemning them to a life of poverty, hopelessness and immeasurable suffering? What happens to a country when 44 million people live in poverty and one in five youth live below the poverty line and a majority of politicians believe it is better to extend tax cuts for the ultra rich rather than invest in jobs, education, health care and the future? In part, it means that youth are no longer viewed as a social investment or as a marker of adult social responsibility. Instead, young people today become an excess burden and are handed over to the marketing experts and the advocates of privatization and commodification. They attend schools that treat them like robots or criminals while the most creative and brilliant teachers are deskilled, reduced to either technicians or cheerleaders for the billionaires’ educational reform efforts. They are no longer children to be nurtured, but a new market waiting to be mined for profits or an army used to fight immoral wars. When deemed necessary, these objectified youth are to be locked up away from the glitter of the shopping malls and the scrubbed and gated middle- and ruling-class communities that float above the dark cesspools of inequality they help to create.

The working-class neighborhood of my youth never gave up on democracy as an ideal in spite of how much it might have failed us. As an ideal, it offered the promise of a better future; it mobilized us to organize collectively in order to fight against injustice; and it cast an intense light on those who traded in corruption, unbridled power and greed. Politics was laid bare in a community that expected more of itself and its citizens as it tapped into the promise of a democratic society. But like many individuals and groups today, democracy is now also viewed as disposable, considered redundant, a dangerous remnant of another age. And yet, like the memories of my youth, there is something to be found in those allegedly outdated ideals that may provide the only hope we have for recognizing the anti-democratic politics, power relations and reactionary ideologies espoused by the new barbarians.

Democracy as both an ideal and a reality is now under siege in a militarized culture of fear and forgetting. The importance of moral witnessing has been replaced by a culture of instant gratification and unmediated anger, just as forgetting has become an active rather than passive process, what the philosopher Slavoj Zizek calls a kind of “fetishist disavowal: ‘I know, but I don’t want to know that I know, so I don’t know.'”(16) The lights are going out in America; and the threat comes not from alleged irresponsible government spending, a growing deficit or the specter of a renewed democratic social state. On the contrary, it comes from the dark forces of an economic Darwinism and its newly energized armies of right-wing financial sharks, shout till-you-drop mobs, reactionary ideologues, powerful, right-wing media conglomerates and corporate-sponsored politicians who sincerely hope, if not yet entirely believe, that the age of democratization has come to an end and the time for a new and cruel politics of disposability and human waste management is at hand.

We are living through a period in American history in which politics has not only been commodified and depoliticized, but the civic courage of intellectuals, students, labor unions and working people has receded from the public realm. Maybe it is time to reclaim a history not too far removed from my own youthful memories of when democracy as an ideal was worth struggling over, when public goods were more important than consumer durables, when the common good outweighed private privileges and when the critical notion that a society can never be just enough was the real measure of civic identity and political health. Maybe it’s time to reclaim the spirit of a diverse and powerful social movement willing to organize, speak out, educate and fight for the promise of a democracy that would do justice to the dreams of a generation of young people waiting for adults to prove the courage of their democratic convictions.

Footnotes:

1. Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, “Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History” (New York: Routledge, 1992), p. 53.

2. On the history and rationality of neoliberalism, see the excellent work by David Harvey: for instance, “A Brief History of Neoliberalism” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); “The Enigma of Capital and the Crisis of Capitalism” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010). See also Henry A. Giroux, “Against the Terror of Neoliberalism” (Boulder: Paradigm Publishers, 2008).

3. For a brilliant analysis and critique of Bush’s and Obama’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, see the various books by Andrew Bacevich, particularly, “Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War” (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2010); “Limits of Power” (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2009).

4. Figures on the new poverty levels and other indexes of misfortune can be found at Carol Morello, “About 44 Million in U.S. Lived below Poverty Line in 2009, Census Data Show,” Washington Post (September 16, 2010); “Census Reports More Children Living in Poverty: Implications for Well-being,” Trends, Child – Research Update (September 16, 2010); Erik Eckholm, “Recession Raises Poverty Rate to a 15-Year High,” New York Times (September 16, 2010), p. A1.

5. Amy Goldstein, “Two Views about What Government Needs to Do about Poverty,” Washington Post (September 16, 2010).

6. Faiz Shakir, Benjamin Armbruster, George Zornick, Zaid Jilani, Alex Seitz-Wald and Tanya Somanader, “Intolerable Poverty in a Rich Nation,” The Progress Report (September 20, 2010).

7. See William Rivers Pitt’s passionate and insightful commentary on Huckabee’s comments and how politically and morally bankrupt they are: Pitt, “Sick Bastards,” Truthout (September 22, 2010).

8. For an excellent article on the politics of austerity and the need to apply such measures to the rich rather than the middle- and working-classes, see Richard D. Wolff, “Austerity: Why and for Whom?” In These Times (July 15, 2010).

9. Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso Press, 2004), p. 33.

10. Zygmunt Bauman, “The Art of Life” (London: Polity Press, 2008), pp. 88-89.

11. I think E. J. Dionne Jr. gets it right in his analysis of how marginal the Tea Party is to American politics. See his “The Tea Party: Tempest in a Very Small Teapot,” Washington Post (September 23, 2010), p. A27. See also the important book by Will Bunch, “The Backlash: Right-Wing Radicals, High-Def Hucksters and Paranoid Politics in the Age of Obama” (New York: Harper, 2010).

12. Bob Herbert, “Two Different Worlds,” New York Times (September 17, 2010), p. A31.

13. See for instance, Michael Schwalbe, “Rigging the Game: How Inequality Is Reproduced in Everyday Life” (New York: Oxford, 2008) and Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, “The Spirit Level: Why Equality Is Better for Everyone” (New York: Penguin Books, 2010).

14. Jane Mayer, “Covert Operations: The Billionaire Brothers Who Are Waging a War Against Obama,” The New Yorker (August 20, 2010).

15. Richard Hofstadter, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” Harper’s (November 1964), pp. 77-86.

16. Slavoj Zizek, “Violence” (New York: Picador, 2008), p. 53.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.