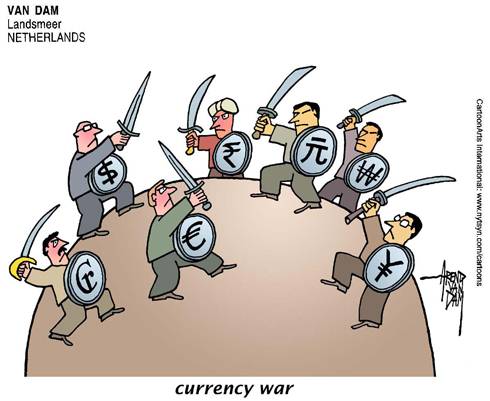

Chinese officials are making increasingly frantic and bizarre statements in response to growing criticism of China’s currency policy.

At a speech in Brussels on Oct. 6, Prime Minister Wen Jiabao warned that too quick a rise in the value of the renminbi would eventually lead to unrest: “Many of our exporting companies would have to close down, migrant workers would have to return to their villages,” he said. “If China saw social and economic turbulence, then it would be a disaster for the world.”

But other emerging markets have experienced currency appreciation, so how is it that if China moved modestly in the same direction, it would be “a disaster for the world”?

Judging by the increasing intensity of China’s protests, there seems to be a consensus that more international pressure must be placed on China. But how?

Martin Wolf, a columnist at The Financial Times who pointed out in a recent article that a currency war with China is all but inevitable, basically agrees with me on the economics, but he calls for financial rather than trade pressure.

I don’t quite understand the suggestions that he, along with commentators like Fred Bergsten, director of the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics, or Daniel Gros, director of the Centre for European Policy Studies, a Brussels think tank, have put forward as alternatives.

Mr. Bergsten called for countervailing intervention in an Oct. 3 column in the Financial Times, noting that as “China or Japan buy dollars to keep their currency substantially undervalued, the U.S. should sell an equivalent amount of dollars to push back.” But how would this work?

China’s intervention is so effective because of its capital controls, which restrict the amount of foreign investment entering the country. As Mr. Gros points out in a September posting on the policy center’s Web site: “China’s capital controls prevent the United States, Japan and the European Central Bank from retaliating; there are simply no significant yuan assets that foreigners are allowed to invest in.”

Do you like this? Click here to get Truthout stories sent to your inbox every day – free.

Mr. Gros then proposes limiting Chinese purchases of American assets instead. But how can the United States do that? It can exclude China from buying government debt at debt auctions, but how to stop China from buying those debts on the secondary market?

Even if the United States Congress passed a rule to that effect, why wouldn’t the Chinese just launder the money through offshore hedge funds? Absent broad-based capital controls in the United States, which would be a bigger step than a countervailing trade duty, I just do not understand the mechanics of this theoretical retaliation.

It seems that people are looking for innocuous ways to deal with this problem, and there aren’t any.

———————-

Backstory: Increased Tensions

In recent months President Barack Obama and several members of the United States Congress have issued strong warnings to China regarding its apparent attempts to devalue its currency, the renminbi. Chinese officials have repeatedly insisted that its currency fluctuates with market forces.

In order to avoid a trade war, American officials have stopped short of officially branding China a currency manipulator. On Oct. 15, the Treasury Department even went so far as to delay the release of its semiannual report on foreign exchange rates to avoid provoking an all-out confrontation with Beijing. But on the same day, the Office of the United States Trade Representative also launched an investigation into the Chinese government’s subsidies for clean energy technologies.

The Chinese responded swiftly. On October 17, Zhang Guobao, a top economic official, lambasted the Obama administration at a press conference, accusing American trade officials of playing election-season politics.

“What do the Americans want? Do they want fair trade? … I think more likely, the Americans just want votes,” Mr. Zhang said. He warned that Americans “cannot win.”

Two days later, the China Daily, a Beijing-based English newspaper, reported that the nation was considering cutting its rare-earth exports, which are widely used in technological products like cell phones and radar equipment, by up to 30 percent next year. According to industry officials, that same day China began to halt shipments to the United States and Europe. Chinese officials have denied these reports, calling them “false” and “groundless.”

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Paul Krugman joined The New York Times in 1999 as a columnist on the Op-Ed page and continues as a professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 2008.

Mr Krugman is the author or editor of 20 books and more than 200 papers in professional journals and edited volumes, including “The Return of Depression Economics” (2008) and “The Conscience of a Liberal” (2007).

Copyright 2010 The New York Times Company.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.