WASHINGTON — WikiLeaks’ release of tens of thousands of classified government documents on three separate occasions this year has prompted U.S. officials to add layers of new safeguards, but that very impulse has sparked a debate among experts about whether those new protections might make national security secrets more vulnerable, not less.

Of particular concern is that officials will be tempted to keep documents under wraps by giving them higher classifications so that fewer people have access to them. That sort of thinking, some argue, is exactly what created the situation where a disaffected Army private in Iraq could download the confidential reports of ambassadors and generals on their meetings with top foreign officials and give them to WikiLeaks.

“Too much information is being called classified, and we are protecting trivia and crown jewels with the same level of security,” said Steven Aftergood, the director of the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists. Classifying more “is a predictable reflex (in light of WikiLeaks), but I think it needs to be thought through carefully.”

Since WikiLeaks began this week publishing classified State Department cables that date back to 1966 and touch on nearly every international issue, the State Department removed its cables from the Defense Department’s Secret Internet Protocol Router Network, or SIPRNet, the Pentagon’s classified computer system, and the White House has ordered agencies across government to look for better ways to protect information.

In its announcement, the White House said that every government agency that deals with classified information has been ordered to assemble a team “of counterintelligence, security, and information assurance experts” to review the agency’s procedures for “safeguarding classified information against improper disclosures.”

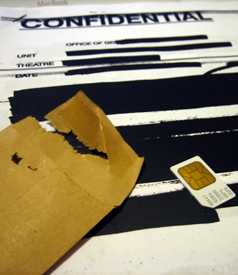

Suspicion of providing WikiLeaks with hundreds of thousands of classified documents has fallen on Pfc. Bradley Manning, 22, who as a Baghdad-based intelligence specialist was given clearance to access confidential and secret documents as part of a Pentagon effort, begun in the 1990s, to make as much information as possible available to combat units. He is now charged with illegally using and disclosing classified information.

Aside from combat reports, however, Manning also had access to documents that had nothing to do with his responsibilities in Iraq, including a 1989 cable written days before the U.S. invasion of Panama; a cable from Karl Eikenberry, the U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan, about corruption in the government of Afghan President Hamid Karzai, and even a memo from the ambassador to Kyrgyzstan that recounted catty comments made two years ago by Great Britain’s Prince Andrew.

The problem, some experts argue, is that the documents Manning needed access to — unconfirmed reports of bombings, attacks and kidnappings across Iraq — were routinely classified “secret” — even though the vast majority of the incidents they recounted were certainly already widely known, at least to the victims and the perpetrators.

Such over-classification isn’t isolated. The U.S. government, which has three broad classes of classified documents — confidential, secret and top secret — often classifies public events as “secret.”

Some of Osama bin Laden’s early declarations and interviews were classified even though news reports about them had been published by some of the world’s largest newspapers, said Michael Scheuer, a retired CIA analyst who served as the agency’s chief of the bin Laden desk from 1996 to 1999. He left the CIA in 2004.

The Obama administration sought to deal with the issue of over-classification in 2009, when President Barack Obama issued an executive order calling for a review of how documents are classified, saying none can remain classified indefinitely.

The order sought to avoid “over-classification” by providing training every two years to officials authorized to classify documents and requiring officials to regularly review documents to determine if they should remain classified.

It ranked as “equally important priorities” both the “accurate and accountable application of classification standards” and the “routine, secure and effective declassification.”

But even in July of this year, the goal of avoiding over classification hadn’t been met, Gen. James Clapper, the current director of national intelligence, said during his confirmation hearing.

“My observations are that this is more due to just the default — it’s the easy thing to do — rather than some nefarious motivation to, you know, hide or protect things for political reasons,” Clapper said. “Having been involved in this, I will tell you my general philosophy is that we can be a lot more liberal, I think, about declassifying, and we should be.”

Five days later, the first batch of WikiLeaks documents were made public. Many included the names of Afghans who’d cooperated with coalition forces.

And by October, in anticipation of the second batch of documents from WikiLeaks, which focused on the Iraq War, Clapper wasn’t as eager to share information:

“We’re working on information-sharing initiatives across the board, but the classic dilemma of ‘need to share’ versus ‘need to know’ is still with us,” he told a conference of intelligence experts. “The WikiLeaks episodes represent what I would consider a big yellow flag. I think it’s going to have a very chilling effect on the need to share.”

That change in tone appears reflexive — and dangerous, Aftergood said.

“The response to the Manning story may be an impulse to increase secrecy and increase classification far beyond where we already are. And we already are in a bad place by universal consent,” he said. “The right answer is not more secrecy but smarter secrecy.”

The classification system was developed during the Cold War, when the government determined from the top who needed to know what information. Often that information would stay within an agency, not be shared throughout government.

But with a burgeoning number of agencies that gathered intelligence, there were complaints that government officials stovepiped information. Those complaints reached their peak after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and were central to a key recommendation of the 9/11 Commission that investigated the attacks: Agencies needed to share information.

“The culture of agencies feeling they own the information they gathered at taxpayer expense must be replaced by a culture in which the agencies instead feel they have a duty . . . to repay the taxpayers’ investment by making that information available,” the commission concluded.

So instead of hoarding information, intelligence officials were encouraged to share it across the government. It dovetailed with a Pentagon campaign begun after the 1991 Gulf War to get more information to soldiers in the field.

“Part of the open access was so that no one could come back and say my access didn’t allow me to get to information that would have stopped the attack,” Scheuer said.

Unlike during the Cold War, when the enemy was one or two large nations and their allies, the attitude became that a threat could come from anywhere. You don’t know what you need to know, particularly in a decentralized war such as a counterinsurgency where information and intelligence are fluid and lower-ranking soldiers have greater responsibilities.

At the same time, intelligence officials began classifying more.

Both Aftergood and Scheuer agree that the urge to classify more generally goes up during wartime. That urge is also fed by concern after 9/11 that the U.S. couldn’t reveal some of its controversial tactics, such as waterboarding prisoners, without generating a public outcry.

As a result of the push to share information while at the same time classifying more, more people have access to documents with higher classifications.

“It’s easier to give someone access to all the databases than to just what he needs. It is tremendously expensive to divide up that information,” Scheuer said.

The Defense Department is the largest source of classified documents largely because of its 1.4 million active duty soldiers, nearly all with some classification access.

There were supposed to be safeguards against information stealing, but with so many people using the Pentagon’s system, monitoring how much any individual reads is nearly impossible.

On Aug. 12, in the wake of the first WikiLeaks document release, Defense Secretary Robert Gates ordered the Pentagon to disable Defense Department classified computers from loading information onto removable storage devices.

Two people now are required to download documents from the classified system; Manning allegedly pretended to be listening to music by Lady Gaga, singing and humming the lyrics so that passersby would think the running CD drive was playing music, not recording thousands of classified documents.

Still, Scheuer worries that the current concern about WikiLeaks will cause the government to draw the wrong lesson about how best to protect information.

“I think people drew the wrong lesson from the 9/11 commission,” he said. “It was not just about sharing information. It was about acting on the information you have.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $50,000 in the next 9 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.