Clearly, the European Union’s bailout of Ireland has not reassured the markets, which are still shaky as the nation’s borrowing costs continue to climb.

It’s hard to escape the suspicion that the European officials involved in the loan process are completely out of their depth.

They know how to deal with liquidity problems, but it appears they cannot come to grips with the reality that Ireland’s financial woes require more than buying the country a little more time.

It’s as if policy makers and Irish officials are currently having the following dialogue:

“Ireland really can’t afford to pay these debts.”

“Here’s a credit line!”

“No, really, we just can’t afford to pay.”

“Here’s a credit line!”

It’s like watching a car wreck.

And, as I read it, European policy makers still — still! — view the crisis as a confidence problem, not a deeper problem rooted in the Irish economy’s fundamental structure. The Irish bailout, at a cost of about $112 billion, is not what one normally thinks of as a bailout — it’s simply an agreement to lend Ireland funds at more or less safe market rates.

Now, this represents a considerable gift, since Ireland would be in a tough situation without such funding, and it would have to pay very high interest rates to borrow on the private market. But if we think about why this is true, we can also see why the bailout isn’t likely to succeed.

Given the cost of rescuing Ireland’s banks and the damage harsh austerity measures are inflicting on its economy, investors are understandably skeptical that the Irish government will actually be able to meet its commitments to pay its debt. That’s why interest rates are high — to compensate for a possible default.

Now, this process is self-reinforcing: higher rates make it even harder for Ireland to meet its commitments, which leads to still higher rates, and so on. The European bailout basically short-circuits this vicious circle.

But the bailout will only work if the vicious circle is the problem, as opposed to being a symptom. That is, it will work only if Ireland is the fundamentally sound victim of a self-fulfilling panic. And that’s a hard claim to make.

For an alternative to Ireland’s decision to guarantee all its debts, employ savage austerity measures to pay those costs, and, of course, keep the euro as its currency,  consider Iceland’s approach. It has been heterodox: restructuring a large amount of debt, using capital controls and fostering devaluation. And Iceland is showing surprising resilience lately.

consider Iceland’s approach. It has been heterodox: restructuring a large amount of debt, using capital controls and fostering devaluation. And Iceland is showing surprising resilience lately.

So if the problem is not one of confidence and liquidity, what would Ireland (and Greece and Portugal) need? Actual debt relief. Yet that is not on the table.

Ireland, like Greece, is now insulated from the need to go to the market — but it still faces an enormous debt load (gross debt is projected to remain above 120 percent of gross domestic product through the end of next year), possibly made worse by deflation and stagnation. For Ireland, the situation has simply not been resolved.

—————

BACKSTORY: Troubles May Cross Borders

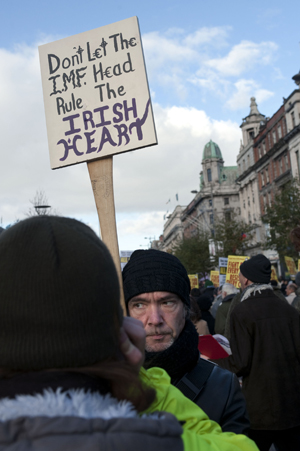

Despite the International Monetary Fund and European Union’s joint pledge to bail out Ireland’s failing banking system, which was officially approved by finance ministers on Nov. 28, Irish bond yields have continued to rise.

This upward trend means that bond prices have been dropping, while investors are still nowhere to be found — a dangerous predicament for the fiscally imperiled country. After all, the Irish government was hoping that news of the $112 billion bailout would encourage capital market investment to return to its shores.

Other European officials shared these hopes because this debt crisis poses dangers to European countries beyond Ireland, especially those heavily invested in Irish debt, including Belgium, Germany and France. As European ministers debate how best to contain the damage a possible Irish default might cause euro-zone economies, they are also beginning to warily assess the situations of member nations that are similarly indebted.

In response to the debt crisis in Ireland, Portugal’s bond yields also have risen to levels nearing record highs, prompting discussion of possible bailouts to Portugal and Spain, since their economies are closely linked. Following the announcement of the Irish bailout, Portuguese officials said that their country did not need any assistance. But then the Bank of Portugal released a report on Nov. 30 saying that major debt difficulties had forced banks into a “permanent and large-scale” dependence on the E.C.B., and that this funding was “not sustainable.”

© 2010 The New York Times Company

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Paul Krugman joined The New York Times in 1999 as a columnist on the Op-Ed page and continues as a professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 2008.

Mr Krugman is the author or editor of 20 books and more than 200 papers in professional journals and edited volumes, including “The Return of Depression Economics” (2008) and “The Conscience of a Liberal” (2007). Copyright 2010 The New York Times.

We have 9 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.