Part of the Series

Solutions

Troops or Private Contractors: Who Does Better in Supplying Our Troops During War?

Charles M. Smith

In testimony before the House on March 11, 2010, Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics, Dr. Ashton B. Carter, stated, “All studies show that that [organic support, i.e. using troops] is more expensive than contractors and a distraction from military functions for military people.”(1) While this is sometimes an accurate statement, the Army should not just automatically choose contractor support over organic support without serious and honest additional analysis. With the continuing experience of extensive LOGCAP logistics support for Afghan and Iraq wars, the Army has the opportunity to re-evaluate decisions to use contractors for combat service support. The main support contractor for most of the time of these current wars, KBR, has had many failed reviews and received much criticism by DoD investigators and Congress. With the price tag of KBR's LOGCAP contracts hitting above $40 billion, there are many lessons to be learned from their cost and performance failures. Such a review can evaluate the additional risks posed by contractors on the battlefield, along with any cost savings.

Cost Comparison

The major cost comparison study of troop versus KBR LOGCAP support was performed by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in 2005. This study was performed during the first two years of combat in Iraq and had significant data. The CBO compared Task Order 59 on the LOGCAP III contract, which provided support to Joint Task Force Seven (CJTF-7), the initial designation of troop units in Iraq. Task Order 59 accounted for over 50 percent of LOGCAP costs during the two years it was in effect.

The CBO estimated the number of Army units necessary to carry out the full range of tasks which Task Order 59 provided for JTF-7. They determined that “177 units of 38 distinct types, populated by 12,067 soldiers” would be required. They took into account units already in the military force structure, but unavailable because they are assigned to other missions, such as Korea. For their model, CBO assumed a 20-year period with two contingency operations and two periods of peacetime, in which units were trained and reconstituted. They calculated the cost per soldier, with the average length of service and the accumulation of veterans and retirement benefits. Unlike previous studies, the CBO factored in the different costs of reserve and regular Army units.

Based on these calculations, the cost of troop support would be $78.4 billion for the 20-year period. LOGCAP support is calculated to cost $41.4 billion for this period. Based upon the CBO calculations, the cost difference over a 20-year period would be $37 billion dollars, in 2005 dollars. The study found that organic support costs approximately 90 percent more than using contractors.

The CBO study examined a variety of operational scenarios, differing lengths for missions and peacetime, and found that the cost differential was not sensitive to these variations. The study is, however, extremely sensitive to a major assumption of the analysis, the Army's rotation schedule. The Army policy is for a three-year rotational schedule. One year is spent performing a mission, followed by a year of reconstitution and a year of training for the next mission. Given this schedule, each unit created to replace the LOGCAP contract must have two other similar units to complete the rotation cycle. If the Army could live with a two-year rotational schedule for support units, the cost differential between organic support and LOGCAP would be significantly reduced especially since, in reality, the Army has not strictly kept to a three-year schedule and many of our troops are on their fifth or sixth deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan.

While this CBO report is the most complete study of the costs of using LOGCAP prepared, there is room for improvement and the addition of more real wartime experience data. The CBO study was based upon costs for Task Order 59 in the LOGCAP III contract as they were understood in 2004. Since that time, we have additional experience with the price under Task Order 59 and the follow-on Task Orders for the same services, Task Orders 89, 139 and 159. This additional experience indicates a somewhat higher cost and some additional expectations for the tasks performed. The CBO determined an average per-year cost of $4 billion for LOGCAP during a contingency operation. The Army's experience to date would indicate that cost should be approximately $5 billion. This would add another $10 billion to the LOGCAP 20-year cost.

Additional Costs of LOGCAP

Based upon the actual experience of LOGCAP in Iraq, Afghanistan and Kuwait beyond the 2005 date of the CBO report, there are important costs of using LOGCAP, which the CBO did not take into account. One flaw in the CBO study that has became clear during actual war experience in 2004 is that the DoD was not able to manage and oversee the LOGCAP contract with the resources and personnel they had on hand. Had these oversight resources been available, the cost and quality of LOGCAP performance could expect to be improved. The resources were located in five organizational sectors:

1. Army Contracting Command required more contracting positions to manage the LOGCAP contract.

2. Army Sustainment Command required more resources to manage the LOGCAP Program office, including the reserve component known as the LOGCAP Support Unit.

3. The Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) required more resources to administer the LOGCAP contract on site and at headquarters units.

4. The Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA) required more resources to audit the contractor work under cost-type contracts.

5. Supported units required resources to provide Contracting Officer Technical Representatives (COTRs).

The cost of establishing a permanent structure for these five government oversight organizations that can support use of LOGCAP in contingency (war) operations must be added to the LOGCAP comparison costs. These will be full-time positions for both military and civilians, and will accrue costs in peacetime and during a contingency. Post-retirement benefits for military and benefit costs for civilians must be included. In other words, it takes many more military and government civilian personnel to oversee a contractor in war situations than the Army ever figured when it decided to put contractor personnel, instead of military and civilian personnel, to support the Army during an active war.

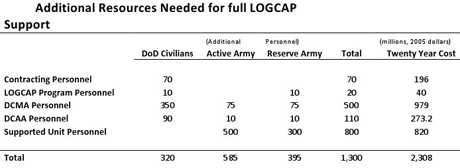

Based upon analysis I gave to the Congressionally mandated Commission on Wartime Contracting, testimony by DCMA and DCAA leaders and Government Accountability Office (GAO) studies, I have done a rough calculation of these additional costs:

Click image to enlarge.

Combining the adjusted cost of government support, based upon additional data from follow-on task orders with these costs of management and oversight, we would add $12.3 billion to the cost of LOGCAP support during a 20-year period. These adjusted numbers would reduce the cost difference to $24.7 billion for the 20-year period. Therefore, it shows that private contractors may not be the bargain the Army suggested when they lobbied the Congress for the private contractor funding.

A more difficult cost to quantify is the larger overall impact which use of LOGCAP has had in the war theater. Private contractor LOGCAP support is generally first on the spot and performs a significant amount of subcontracting and hiring. A significant portion of the approximately $5 billion per-year LOGCAP costs went to subcontractors. The local market in Iraq and Afghanistan for nontactical vehicles, food services, gravel, plywood, and other commodities saw a significant increase in demand, which led to prices being inflated. Following LOGCAP into theater, the Corps of Engineers, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the State Department also commenced contracting for new construction and reconstruction. They bought many of the same services as LOGCAP, but at inflated prices.

Similarly, the cost of labor acquired through labor brokers or in the local economies saw an increase in wages. When the reconstruction contracts were awarded, KBR experienced numerous attempts to hire their general managers and engineers for the new projects. Each attempt resulted in a ratcheting effect on the wages of American workers in those labor categories. Some of these costs were felt by the LOGCAP program, while others were transferred to State and USAID contracts. These hidden costs have not been thoroughly examined.

I have not seen any economic analysis of these effects in the costs that the US has paid for all contracts in theater. However, it is obvious that military personnel support would significantly dampen these costs. Based on the experiences of using military personnel in past wars, as it has been done throughout most of our history, centralized acquisition of supplies and services in theater would also have a significant cost-control effect.

Again, we can make some back-of-the-envelope calculations. With total yearly spending in Iraq on all contracts escalating significantly, and the assumption of a fairly set supply of people and materials, the additional cost could be in the range of $500 million to $1 billion per year, during operations. Over the CBO 20-year period, the cost would be in the range of $7.5 billion. This would once again reduce the 20-year cost differential, between LOGCAP and military personnel support to $17.2 billion, and this number could be further reduced due to costs that have not been known due to the chaotic accounting that has occurred for years in these wars.

Finally, the LOGCAP IV contract allows for significantly higher fees than the LOGCAP III contract examined by GAO in the 2005 study. Under LOGCAP III, KBR's maximum fee was 3 percent of estimated costs. Under LOGCAP IV, the maximum fee can rise to the FAR maximum of 10 percent. This increased fee structure would add an additional $2 billion in costs to the 20-year period.

Considering the Risks of LOGCAP

The use of LOGCAP as opposed to military personnel support introduces risks into operations. War is a unique enterprise and there are reasons that troops in our war history provided the basic logistics in hostile areas. A thorough and realistic cost/benefit analysis must take these risks into account. There is general agreement on the risks associated with using contractors on the battlefield. They are:

1. There is an inherent authority problem. The contractor must perform according to the scope of work in the contract and not in accordance with the military commander's directions. This relationship is outside of the Army command and control structure. The Army and the contractor have inherently different interests. The managers of the contractor have a fiduciary responsibility to shareholders to maximize profits or minimize losses. This may conflict with providing the Army exactly what they want or need, when the contract is ambiguous about the requirement. Use of a contractor will not ensure that that the military commander gets the performance he wants in the same manner as placing an organic Army unit under his control, especially during times of hostile actions.

2. Experience under LOGCAP III in Iraq, Kuwait and Afghanistan revealed the second major risk area. With contractor support, requirements tend to increase beyond those which military personnel support would have provided. During Phases I and II of operations, where military commanders were not constrained by a budget, they continually added more support to their requirements. It is a very different situation because the costs of the private contractors were not coming out of the commander's budget and logistics limitations. The increased costs for LOGCAP support during these phases were substantially driven by increased requirements. For example, KBR was interested in making sure that the military commanders were happy and would interpret their contract to make sure that certain influential commanders got soft-serve ice cream and pastry-chef desserts on their bases while other units suffered. Organic military units provide support in strict compliance with military regulations and guidance, a more disciplined process.

3. The third major risk to be dealt with concerns continuity of support. Contractors are American citizens with the same rights as you have to change jobs, so they may leave the battlefield for financial, security, or other business reasons. Troops, on the other hand, are under the Uniform Code of Military Justice and cannot walk away from their duties during war. Once the Army develops a force structure, with units to perform support functions, they have assurance of continued provision of the services. While there will be planned rotations, any unit can be ordered to stay until a relief unit is available. Military units will not cease support and will perform as ordered. As contractors are added to the mix, the risk of lost continuity of support will increase.

4. The fourth major risk area is the legal status of civilian contractor personnel and their companies. Military units, government civilians and contractor personnel appear to all have a different legal status when operating in a combat theater. Control of these individuals is a mixed affair of the combatant commander, the supervisory chain and the contractor's management. Contractor personnel are not under the strict rules of the military, and the law that applies to them is murky and uncharted territory. For example, private security contractors in Iraq, such as Blackwater, were known to drive through towns in Iraq shooting at the general population and, then, the troops that would have to patrol those towns would reap the natural anger and discontent of the people of those towns. This and other acts by contractors hurt the goals of the military to try to win the support of the Iraqi public, thus, prolonging the occupation. The military commanders have very little control over this problem and it is a major problem for them.

5. A fifth major risk area is the government's current lack of ability to provide effective oversight of contractor work. One of the lessons of these wars is that effective oversight of work was not conducted for LOGCAP III. The GAO has reported, “Challenges in providing an adequate number of contract oversight and management personnel in deployed locations are likely to continue to hinder DoD's oversight of contractors.” There have been numerous news reports and other investigations showing that KBR greatly abused and gamed the contract, and I was on the inside trying to limit the fraud and mismanagement to no avail.

6. The sixth risk area is a very sensitive risk area involving our evaluation of contractor casualties as opposed to military casualties. One may speculate that military units, performing the same LOGCAP work, would have the same or possibly lower fatality rate, because they are authorized to carry weapons and defend themselves.

There is also an operational risk from using civilians instead of troops. Each soldier, even if they operate the dining facility, carries a weapon and is trained to use it. In the event of an attack on the unit, they can aid in the defense. Contractor personnel do not carry weapons. In the event of attack, they cannot help and must be defended. It is not common knowledge that KBR truck drivers could not carry guns to protect themselves and were often helpless when the Army was overwhelmed by attacks on the truck convoys. This is an additional burden placed on the troops, along with a loss of available combat power; to try to protect all these unarmed personnel.

7. A last area of risk is even more controversial. The use of contractor support appears to obviate what has been called the Abrams' Doctrine. Gen. Creighton Abrams restructured military forces to closely integrate the reserve and guard components with regular Army units. For example, a combat division could not deploy and operate without a reserve transportation unit to move their supplies and a reserve water unit to produce and transport water. There is speculation that Abrams intended this linkage to force leadership to realize that any use of combat forces would require broad support as reserve and guard units were mobilized. Replacing these reserve units with contractors may create a moral hazard in that a president can now commit troops to war without calling up as many reserve and guard units.

An analysis of the use of contractors for combat services must take these risks and any advantages of contractor support into account. On the whole, it would seem that introducing contractors onto the battlefield to provide mission essential support functions introduces significant risk for the commander, which may offset the dubious savings of $750 million per year.

In 2008, Congress amended section 807 of the National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2008 to add a requirement for the secretary of defense to submit an annual inventory of the activities performed pursuant to contracts for services for or on behalf of DoD during the preceding fiscal year. The intent of this action was to encourage insourcing (using DoD personnel) of service requirements. In April 2009, the secretary of defense announced his intent to reduce the department's reliance on contractors and increase funding for new military civilian authorizations. More recently, in August 2010 the secretary of defense announced plans to reduce funding for service support contractors by 10 percent per year from fiscal years 2011 to 2013. Moving troop logistics back to organic support would be the most significant insourcing decision that the military could make.

Unfortunately, Marjorie Censer reports in the February 7 edition of Capital Business that the Army is putting insourcing decisions on hold. Ms. Censer reports, “In a Feb. 1 memo, Army Secretary John M. McHugh suspended any already approved insourcing actions and said he will personally authorize any new proposals.” While the stated reason is that earlier efforts did not save much money, there has obviously been significant contractor pressure to keep these lucrative efforts outsourced to business.

As a starting point to solve this damaging problem and trend, I would recommend a full cost/benefit study of this issue, using the CBO study, to comply with the Army stated wish for savings and improvement, Working with the Army for over 30 years, I learned that there are a lot of very smart, experienced officers, especially lieutenant colonel and colonel rank, who can add the appropriate risk analysis to such a study. The Army can also evaluate the prospect of a reduced rotation schedule for support troops. Congress and the administration should carefully review the results and determine the most effective and efficient way to provide this critical troop support. Our efforts should be to make sure that our troops are not saddled with these severe, additional problems that threaten their safety and mission, all in the name of ambiguous savings. We need to get realistic analysis of this problem before it becomes the permanent new way of supplying our troops with an entrenched corporate lobby that can become very difficult for the DoD to resist.

1. (Carter 2010) I do not quite understand how a soldier assigned to logistics duties is “distracted” from military functions. If we use organic support for logistics, then this is his or her military function. Since this soldier is also available for combat functions, unlike contractors, this improves the Army's combat capability.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.