The occupational hazards, poor working and living conditions, and low wages North Carolina’s tobacco workers face result from deliberate policies, but they can be meliorated by unionization and the freedom for laborers to shop their skills around.

North Carolina has one of the lowest percentages of union members in the country. Yet in this non-union bastion, thousands of farmworkers, some of the country’s least unionized workers, belong to the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC). That gives the state a greater percentage of unionized farmworkers than almost any other.

The heart of FLOC’s membership here are the 6,000 workers brought to North Carolina with H2-A work visas every year to pick the cucumbers that wind up in the pickle jars sold in supermarkets by the Mt. Olive Pickle Company. Not all farmworkers, or FLOC members, are guest workers with H2-A visas, however. In fact, a report last year by Oxfam America, “A state of fear: Human rights abuses in North Carolina’s tobacco industry,” estimates that of the 100,000 farmworkers in the state, only 9 percent have H2-A visas. Almost all the rest have no legal immigration status.

Nevertheless, when workers fall under the union contract, FLOC represents them, regardless of whether they have visas or not. Some contract growers employ both H2-A and undocumented labor – the union doesn’t ask. This is the case for every farmworker union in the country. If a union only tried to represent workers with visas, it would have no power. Only a small minority of the workforce would qualify for membership, and in a given workplace, workers would be divided against each other. The ability of a union to unite workers in action in a workplace is the basis of its strength and its ability to protect rights and win better conditions.

In North Carolina, FLOC has a total of 7,000 members, and 80 percent work in tobacco fields, for the same growers who raise the cucumbers for Mt. Olive pickles. That gives the union a base for organizing the tobacco industry, using the same corporate and boycott strategy it used to gain its original agreements here with the Mt. Olive Pickle Company.

This time, FLOC’s adversaries are the world’s largest cigarette manufacturers – Philip Morris, Lorillard Tobacco Company and Reynolds American. None of them actually own land or grow tobacco themselves. They contract with growers and buy what they produce, at a price these manufacturers totally control. Some growers contract for workers through the North Carolina Growers Association (NCGA), where the union has its contract. Other growers hire workers themselves, usually through labor contractors. The NCGA workers all have H2-A visas, while those working for labor contractors are mostly undocumented. Some growers use workers from both entities.

“Conditions for tobacco workers are worse than those for farm workers anywhere else in the country,” says Baldemar Velasquez, FLOC’s president. Velasquez says he’s out to organize all workers, regardless of status. “Just because someone’s undocumented, doesn’t mean they don’t have rights,” he emphasizes.

The hands of Ruben Barrales, a farm worker from Xalapa, Veracruz, show the juice and dirt from tobacco plants. The rancher discourages him from wearing gloves, saying that it would cause him to harm the plants. (Photo: David Bacon)As a hot August sun beats down on a field in Nash County, Manuel Cardenal moves down his row almost at a run. He pauses for a second in front of each tobacco plant, breaking off the new shoots – Cardenal calls them retoños – at the top. They have to be removed so that the growing strength of the plant will flow into the leaves below, making them broad and heavy.

The hands of Ruben Barrales, a farm worker from Xalapa, Veracruz, show the juice and dirt from tobacco plants. The rancher discourages him from wearing gloves, saying that it would cause him to harm the plants. (Photo: David Bacon)As a hot August sun beats down on a field in Nash County, Manuel Cardenal moves down his row almost at a run. He pauses for a second in front of each tobacco plant, breaking off the new shoots – Cardenal calls them retoños – at the top. They have to be removed so that the growing strength of the plant will flow into the leaves below, making them broad and heavy.

Cardenal understands the way tobacco plants grow and knows what must be done to make them productive. He used to have a farm of his own in Estelí, the best-known tobacco region of Nicaragua, a country famous for cigars.

Five other workers like him race down their own rows, deftly choosing and plucking out the right parts of the right plants. To do this well, rancher Corey (they don’t actually know his full name) says they have to use their bare hands. Gloves would be too encumbering, he says, and might damage the plants. In addition, they’re being paid a piece rate. The workers have to work fast just to make the minimum wage. Corey says the whole field has to be finished by the end of the day.

By one in the afternoon, the temperature has reached 102 degrees. Cardenal’s arms shine with sweat. Since six that morning, when they went into the field, the hands of all six workers have been covered with a sticky green tar – the residue of tobacco juice and gum from the leaves. The same thing that gives cigarettes and cigars their kick – the nicotine – is not just present in the tar, but permeates even the dust in the air. Anyone walking into the field starts to feel that heady sensation you get from smoking the first cigarette of the day.

“I feel it as soon as I start work,” Cardenal says. “Then, after my body gets used to it, I can hardly feel it at all. But I know I’m absorbing it all day.” The other workers say they still feel light-headed, though, even though hours have passed since they started work. When the heat reaches its peak, they sometimes feel nauseous, as well.

Another component of the sticky tar is the residue of pesticides sprayed on the plants. Growers aren’t supposed to send workers into the field for 72 hours after they spray. Some do anyway, but even past that limit, chemicals remain on the plants’ sticky leaves.

“I know I’m getting exposed, but I don’t know what I’m exposed to,” Cardenal says. “On my own farm, I’d at least know what I was using to kill insects. But here, I have no idea, and the growers never tell us.”

Manuel Buendia, a farm worker from Alamo in the state of Veracruz, Mexico, trims the tops of tobacco plants so that the leaves will grow larger. (Photo: David Bacon)The reason all six workers know so well the operations needed to grow tobacco is that they all come from the tobacco regions of Mexico and Central America. They’ve all worked in those fields at home. Ruben Barrales and Manuel Buendia come from Veracruz, where tobacco leaves even form part of the coat of arms of Alamo, Buendia’s hometown. Maynor Gonzalez, his brother Ismail and Francisco Escobar all come from Santa Rita in Honduras. That town is an hour from San Pedro Sula and the port of Puerto Cortez, where Honduras manufactures and exports its cigars.

Manuel Buendia, a farm worker from Alamo in the state of Veracruz, Mexico, trims the tops of tobacco plants so that the leaves will grow larger. (Photo: David Bacon)The reason all six workers know so well the operations needed to grow tobacco is that they all come from the tobacco regions of Mexico and Central America. They’ve all worked in those fields at home. Ruben Barrales and Manuel Buendia come from Veracruz, where tobacco leaves even form part of the coat of arms of Alamo, Buendia’s hometown. Maynor Gonzalez, his brother Ismail and Francisco Escobar all come from Santa Rita in Honduras. That town is an hour from San Pedro Sula and the port of Puerto Cortez, where Honduras manufactures and exports its cigars.

Migration to North Carolina from Honduras and Nicaragua is relatively recent, but the flow of people from Veracruz dates back to the mid 1980s. The Veracruz flow is connected to the passage of the Immigration Reform and Control Act, and later the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Central American migration, with its origin in the exodus of refugees from its civil wars, got a big boost following the passage of the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA).

The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, best known for its immigration amnesty, also modified and expanded a previous guest-worker program. It took a previous H-2 visa category, a vestige of the old bracero era, and divided it into two categories – H2-A for farm labor, and H2-B for unskilled non-agricultural workers. Once the law took effect, US growers could recruit workers in other countries and bring them to the United States on the H2-A work visas. Workers with H2-A visas can only work for the length of their employment contract – less than a year – and then must leave. They can only work for the grower or contractor who hires them. Importing contract labor to the United States on temporary work permits was halted when the notorious bracero contract labor scheme was ended in 1964. The H2-A visa program, however, reopened the door.

Soon after the law took effect in 1986, hiring agents for North Carolina growers appeared in Veracruz, offering people the chance to work in the United States on the guest-worker visas. In the tobacco regions, they found plenty of takers.

During that period, Mexico’s constitution was changed to allow the sale of communally owned land, the ejidos. In a wave of free market reforms, the government dissolved Tabamex – the agency that helped small tobacco farmers market their product. Then NAFTA took effect in 1994, taking down the barriers on agricultural imports to Mexico. It became very difficult for Mexican farmers in many crops to compete against imports from the United States. Small farmers who couldn’t sell tobacco or corn for a price that paid the cost of growing it began to sell off their land to survive.

While these changes caused an enormous crisis in rural areas throughout the country, Veracruz suffered more than most states because it is more dependent on agriculture. Unable to survive on their land in Veracruz, tobacco farmers began to come north as contract workers, to the fields of North Carolina.

Once their original work contracts ended, many H2-A workers simply stayed in the United States without visas and became undocumented. Over time, others came north on their own to join friends and relatives already living in North Carolina. A pool of Mexican workers began to grow, most from Veracruz. Eventually, they were joined by people arriving from Central America as well, displaced by CAFTA. That agreement took effect in 2005 and unleashed the same economic forces NAFTA set loose earlier on rural communities in Mexico.

In the evening, workers return to the Royce Bone labor camp in a bus from the fields. (Photo: David Bacon)According to the US Department of Labor, 7 percent of the nation’s 1.4 million farmworkers have H2-A visas, while 53 percent have no visa at all. Of the 103 workers interviewed for the Oxfam report, almost all were undocumented. A quarter said they were paid wages less than the legal minimum. This is not unusual. In California, the Indigenous Farmworker study conducted by Rick Mines found that a third of the farm laborers it surveyed were paid less than the state’s minimum wage.

In the evening, workers return to the Royce Bone labor camp in a bus from the fields. (Photo: David Bacon)According to the US Department of Labor, 7 percent of the nation’s 1.4 million farmworkers have H2-A visas, while 53 percent have no visa at all. Of the 103 workers interviewed for the Oxfam report, almost all were undocumented. A quarter said they were paid wages less than the legal minimum. This is not unusual. In California, the Indigenous Farmworker study conducted by Rick Mines found that a third of the farm laborers it surveyed were paid less than the state’s minimum wage.

A majority of those interviewed in the Oxfam survey reported the same physical symptoms Cardenal and his coworkers describe – a syndrome called green tobacco sickness – and most had no gloves or other protective equipment. Only a third said there were toilets in the fields where they worked. Every year, North Carolina’s Department of Labor reports the death of several field laborers from heat exposure.

Most farm workers in North Carolina live in labor camps, which are like small company towns where workers depend on the employer for housing, transportation and food. Almost all those surveyed complained of problems like dilapidated barracks, inadequate showers and toilets, lack of heat or ventilation, and insect infestations.

Today, conditions for H2-A workers are better than those described by the undocumented, primarily because most belong to a union, the FLOC. This was not always the case, however.

In 2004, FLOC signed an agreement with the NCGA and the Mt. Olive Pickle Company. The union had mounted a long corporate campaign against Mt. Olive, because it was a non-union competitor to union pickle producers in Ohio and the Midwest. Mt. Olive’s lower labor costs were subsidized by its use of the H2-A program.

Until the signing of the FLOC contract, North Carolina’s H2-A workers were held in a form of low-wage bondage. Federal law requires growers to pay an “adverse effect” wage to H2-A workers, supposedly set high enough so that it doesn’t undermine local wage standards. North Carolina growers, however, were well known for paying less than the legal minimum, and Legal Aid of North Carolina filed many complaints against them. Even today, most growers using the program pay the minimum wage or slightly above.

To enforce the low-wage regime, NCGA maintained a blacklist, called in its employee manual a “record of eligibility [which] contains a list of workers, who because of violations of their contract, have been suspended from the program.” The “1997 NCGA Ineligible for Rehire Report” listed 1,709 names. The reason for ineligibility was most often given as abandoning a job or voluntary resignation. Legal Aid, however, charged that when workers were fired for complaining, they were given a paper to sign saying they’d quit voluntarily. Among the hundreds of names were also many whose reason for ineligibility was given as “lazy,” “slow,” “work hours too long,” “work too hot and hard,” or “slowing up other workers.”

Workers were warned not to talk with legal aid attorneys and were even told to burn the pink Legal Aid know-your-rights books in a trash barrel at the association office.

The NCGA was organized in 1989 by Craig Eury and Kenneth White, who were fired that year as rural manpower representatives of the North Carolina Employment Security Commission (the state’s unemployment office). The two then set up businesses in North and South Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, and other states for importing guest workers. In 2003, they brought in over 10,000 workers, recruited in Mexico by Manpower of America, which used local enganchadores, or recruiters.

When Mt. Olive signed with FLOC in 2004, NCGA signed as well, since it was the recruiter of the workers employed by the growers who grew the cucumbers for Mt. Olive pickles. As a result of the agreement, FLOC was then able to police the recruitment system. North Carolina is a right-to-work state, which limited the union’s power over hiring, however. Today, a grower has the right to make a decision about whom he hires, but the union maintains a seniority list. If a worker isn’t rehired by a particular grower at the start of the season, the union can get the NCGA to find him or her another job.

The union has a grievance system and workers can make complaints about the kind of health and safety problems they previously had to suffer in silence and fear. The Oxfam report notes that in 2010, FLOC processed more than 700 complaints.

The contract, especially the monitoring of hiring, came at a high price, however. In 2004, FLOC opened an office for that purpose in Monterrey, Mexico. Then, on April 9, 2007, Santiago Rafael Cruz, sent by the union to staff that office, was tied up, tortured and murdered. To this day, the Mexican government has been unable to bring his killers to justice. There is little doubt, however, that he was murdered because the union was threatening the enganchadores who’d been demanding that workers pay bribes to get hired.

Aristeo Luna sleeps beneath bare plywood walls covered in graffiti, like the “13” that is the symbol of a gang based in Los Angeles. (Photo: David Bacon)The fact that union members hired through the NCGA are H2-A workers makes NCGA growers uncompetitive, Velasquez maintains: “They have to provide better conditions, from the adverse effect wage rate to paying Social Security and workers’ compensation,” he says. With Mt. Olive, all growers supplying pickles to the company have to abide by union conditions and pay the same wages. Tobacco, however, is a much larger business, in which NCGA growers with the union contract are competing with non-union growers.

Aristeo Luna sleeps beneath bare plywood walls covered in graffiti, like the “13” that is the symbol of a gang based in Los Angeles. (Photo: David Bacon)The fact that union members hired through the NCGA are H2-A workers makes NCGA growers uncompetitive, Velasquez maintains: “They have to provide better conditions, from the adverse effect wage rate to paying Social Security and workers’ compensation,” he says. With Mt. Olive, all growers supplying pickles to the company have to abide by union conditions and pay the same wages. Tobacco, however, is a much larger business, in which NCGA growers with the union contract are competing with non-union growers.

Since the vast majority of the farm labor workforce in tobacco is undocumented, an agreement with the big cigarette manufacturers will have important differences from the first contract with Mt. Olive and the NCGA. One question is whether undocumented workers will be represented by the union if the industry is forced to sign a master agreement.

Another complexity is the ability of manufacturers to dictate prices to growers. After the US government abandoned its marketing regulations for tobacco, growers lost much of their leverage for negotiating those prices. “Typically, the farmer must sign the contract as written [by the manufacturer] or else lose the chance to grow tobacco during the upcoming season,” the Oxfam report notes. One grower told investigators that “[in] 2010. our crop is going to bring us half a million dollars less than it did in 2009.” Growers today have only one way to respond to price pressure: get workers to produce more for lower wages while spending even less on their food, housing and health. That exerts a continuing downward pressure on wages and conditions in the fields. A union contract would force growers to pay the same wages, essentially taking labor costs out of competition.

H2-A workers have become more expensive in North Carolina because of the union contract. In every other state, where H2-A workers have no union protection, their wages and conditions are often no different from those of undocumented workers. On many ranches, they’re employed and housed together.

Some North Carolina growers see advantages in using H2-A workers, however, especially if competing growers must do the same. One told the Oxfam investigators, “You want to know if you are going to pour all this money into these crops, that if you do everything you are supposed to, you are going to have the labor there till the end of the year to get that crop out of the field.”

“When you hire, you know, a crew leader, an undocumented worker, you are running the risk they are going to leave you before you finish, you run the risk they’re going to leave when you need them the most,” said the grower.

What makes the program desirable to employers, however, also makes workers vulnerable to employer pressure. The means used to make workers dependable – the employment contract, grower control of recruiting and hiring, and the ability of employers to deport workers by firing them – deprive workers of power. In 2007, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s (SPLC) report, “Close to Slavery,” said the program was structurally flawed because workers “are bound to the employers who ‘import’ them. If guest workers complain about abuses, they face deportation, blacklisting or other retaliation.” Regulations to protect workers “exist mainly on paper. Government enforcement … is almost non-existent.”

H2A wages have been especially controversial and have always been hostage to politics. At the end of the Bush administration, the methodology for calculating the adverse effect wage was changed, resulting in a $1-2 wage cut for H2A workers. In March 2010, Labor Secretary Hilda Solis reinstated the old wage and the method for determining it, requiring employers to document efforts to recruit local workers.

“Some improvement is possible with changes in the regs,” argues Mary Bauer, SPLC’s legal director and the “Close to Slavery” report’s principal author. She suggests raising wages and policing recruitment. “But the structure of the program is the real problem. Workers need a visa that’s not dependent on employment. They should come here with a visa that lets them shop their labor around, like any other worker.”

The Oxfam report, however, recommends expansion of the H2-A program instead, claiming this would improve wages and conditions. Allowing growers to import more workers under this program, however, simply means that more workers will endure the abysmal conditions described in the “Close to Slavery” report. Even in North Carolina, where H2-A conditions are better, the reason for the improvement is not the visa, but the fact that workers have a union contract. Without a strong union, conditions would quickly return to what they were before 2004. Yet the Oxfam report makes no recommendation that tobacco manufacturers sign a union contract.

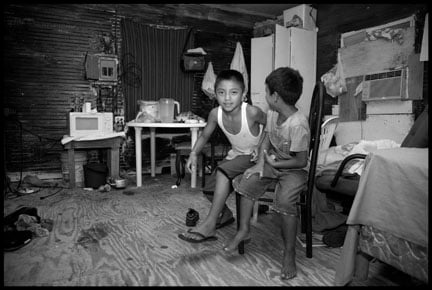

Families, including children, live in the Strickland labor camp. Many come from Mexico, mostly Veracruz, and work in the fields of tobacco and sweet potatoes. (Photo: David Bacon)In the end, the choice faced by the six migrants in the Nash County field is simple. Stay home and go hungry, or come to the United States and survive. Bad conditions and lack of legal status are no deterrent. These workers are not unsophisticated about the situation they face in the United States. Nor do they lack knowledge about the perils of farm labor. They simply have very little power to change their situation other than by leaving home and migrating to North Carolina.

Families, including children, live in the Strickland labor camp. Many come from Mexico, mostly Veracruz, and work in the fields of tobacco and sweet potatoes. (Photo: David Bacon)In the end, the choice faced by the six migrants in the Nash County field is simple. Stay home and go hungry, or come to the United States and survive. Bad conditions and lack of legal status are no deterrent. These workers are not unsophisticated about the situation they face in the United States. Nor do they lack knowledge about the perils of farm labor. They simply have very little power to change their situation other than by leaving home and migrating to North Carolina.

Cardenal asks about the agricultural pesticide DBCP. He cites it as an example of the possible dangers of working in the United States, where he comes in contact with plants and chemicals without knowing their effects. DBCP was used by Dole Corporation on banana plantations for many years in Nicaragua. The chemical was later found to have caused sterility among farm laborers. “Some people got money to settle their legal cases,” he explains, “but the price they paid was very high. They never had children. How do I know that years from now, some chemical on the leaves here won’t cause me a problem like that?”

A strong union would make sure he knows the potential dangers from pesticides. A higher wage, not tied to a piece rate, could allow him to work more slowly using gloves, instead of absorbing nicotine through his bare hands. And a union contract could protect him if he went to rancher Corey and demanded these things, keeping Corey from firing him, evicting him from company housing and even deporting him.

At present, whether he comes into the tobacco field as an H2-A worker or without any visa at all, he runs the risk of retaliation if he demands better conditions. Undocumented workers can always be threatened with the migra. But H2-A workers lose their visas along with their jobs if their boss fires them.

The choices in this field are very circumscribed. But envisioning a more liberating solution for the workers here is not hard. Get rid of NAFTA and CAFTA so that people can earn a decent living at home, making migration only an option, not a necessity. Give a green card – a residence visa – to tobacco workers, instead of an H2-A employment contract or no visa at all. Give workers enforceable organizing rights and require huge corporations to sign union agreements.

It’s just the toxic and deadlocked politics of Washington DC that call real solutions impossible. Today, US immigration policy is largely shaped by the desire of US employers for labor. That’s what limits what’s possible for Cardenal and his workmates. But should it? Can’t migration produce strong communities of people fully able to assert their rights in this country and healthy communities in their countries of origin? Or must it be geared primarily to supplying labor to cigarette manufacturers at a price they want to pay?

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $50,000 in the next 9 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.