Malaga, Spain – The severe crisis crippling Spain is also sparking some creative responses, such the Okonomía project, a teaching initiative that helps individuals and communities to understand the workings of the economy and make more informed decisions to manage their finances.

“Things have gotten so bad, with people out of work, losing their homes and watching their savings vanish, that something has to be done to economically empower people,” said activist Raúl Contreras, one of the academics behind this initiative that in February will open its first school in Benimaclet, a multicultural neighbourhood in the southeastern city of Valencia.

Contreras – an economist who also heads the company Nittúa, which sponsors this project – spoke with IPS about the powerlessness and fear that is taking hold of many people who do not understand how the economy works and how it affects their lives, and are thus made vulnerable to manipulation.

“Doubts, ignorance and fear – in some cases spread intentionally – lead to mistakes, anxiety and difficult situations that could be avoided if people are better informed and equipped to make decisions or choices,” Nittúa’s website reads.

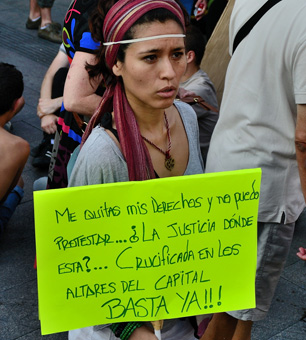

One out of every four economically active persons is currently unemployed in Spain, where dozens of families are evicted daily from their homes for failure to meet their mortgage payments, and the measures implemented by the right-wing government of Mariano Rajoy to address the crisis involve huge cuts to health, education and other basic services.

Hundreds of thousands of people in Spain fell prey to “preferential shares” and other financial product schemes and lost all their savings. As the crisis deepened and banks became desperate for cash, they convinced more and more savers to buy these products, taking advantage of their lack of understanding of the ins and outs of investment, and using misleading and distorted sales pitches.

Okonomía – which is financing its start-up needs through a crowdfunding campaign – calls itself a “popular economics school” that “develops dialectical educational processes, building on the reality and economic knowledge of each participant, to enable participants to understand their economic situation so that they can make informed and conscious decisions, both individually and collectively, that will lead to the transformation of society through economic empowerment.”

The school is formed by professionals from the fields of economics and education and its activities include training multiplying agents who will spread their newly-acquired knowledge in their immediate social environment.

“The school won’t solve people’s problems, but it will provide a toolbox to help individuals make more informed decisions based on their specific needs,” Contreras explained, highlighting the project’s cross-cutting approach to solidarity economy, as it emphasises sustainable alternatives.

While the head of Nittúa stresses the solidarity aspect of this economic model, he says it is not the school’s intent to preach any one model or solution. Rather it seeks to give participants an understanding of economics in general, including a range of economic alternatives, such as ethical banking, responsible consumption, fair trade and the cooperative model.

“A large part of society has realised that a different way of teaching economics is needed,” Carlos Ballesteros, a lecturer on consumer behaviour at Madrid’s Comillas Pontifical University, told IPS. “Ninety-nine percent of the world’s business schools stick close to the neoliberal paradigm,” which is profit-driven and based on maximising earnings.

Ballesteros said that while Okonomía’s target public is civil society as a whole and its main objective is to teach and inform, on the understanding that “the economy is everyone’s responsibility,” it also aims to gather and systematise knowledge on solidarity economy practices that may prove useful to people working in that field.

Okonomía offers semester courses, with in-person classes held every two weeks. The methodology is based on the popular education model developed by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire (1921-1997), who believed that “to teach is not to transfer knowledge but to create the possibilities for the production or construction of knowledge.”

In each session an issue is presented and material is provided to facilitate reflection. “The learning process is a group activity. The classes are not lectures, but rather dialogue-based and interactive,” Contreras said.

He added that after each session the conclusions drawn from the group’s discussions are published online and posted in an intranet, which will form a database of the school’s results, a sort of “Wikipedia of Popular Economy”.

Economist Arcadi Oliveres, one of Okonomía’s advisers, said this project is valuable because it “seeks to reveal to the people the underlying workings of the economy” and “because we’re really in the dark” when it comes to the financial world, he told IPS.

Oliveres, a professor of applied economics at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, believes that “people don’t know that there are alternatives to the traditional economic system” and calls for critically aware citizens who can make informed decisions.

Independently of how financial markets and governments behave, the actions of common citizens also have an impact on the economy, so that people must be conscious that they too can make irresponsible choices as consumers or that their deposits can go to financing environmentally-harmful corporate activities, the economist argued.

“We have to start asking ourselves where our money goes – what do I do with my savings, where do I deposit them and why? – and learn to take control of our finances,” Contreras said.

The aim of the school is to help people “understand and then make free, but conscious decisions,” he added.

The expert noted that he has not found similar projects anywhere else in the world and that Okonomía, which combines a methodology inspired by Paulo Freire with social innovation methods, has the potential to be replicated outside of Spain “with the support of the social fabric of neighbourhoods and communities”.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.