At the Ali Enterprises garment sweatshop in Pakistan in 2011, 300 people burned to death – the largest factory fire in world history. Last year in Bangladesh, workers jumped from the windows of the burning Tazreen factory because the doors were locked, falling to the pavement below as their sisters had done in the notorious Triangle Shirtwaist fire in New York City in 1911. In the Foxconn plant in China, where the iPads and iPhones are assembled, workers were pushed so hard that they began to kill themselves in 2010.

And during the week of April 21 this year, more than 700 workers were killed when the Rana Plaza building collapsed. Factory owners refused to evacuate the building after huge cracks appeared in the walls, even after safety engineers told them not to let workers inside. Workers told IndustriALL union federation representatives they’d be docked three days pay for each day of an absence, and so went inside despite their worries.

Not good for the corporate image of Walmart, whose clothes were sewn at Tazreen, or Apple, whose iPads and iPhones are put together at Foxconn. Not good for JCPenney, Benetton or the Spanish clothing brand El Corte Inglés, whose labels or cutting orders were found in the rubble at Rana Plaza. According to the International Labor Rights Forum, “one of the factories in the Rana complex, Ether-Tex, had listed Walmart-Canada as a buyer on their web site.”

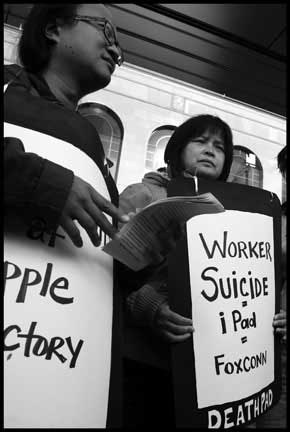

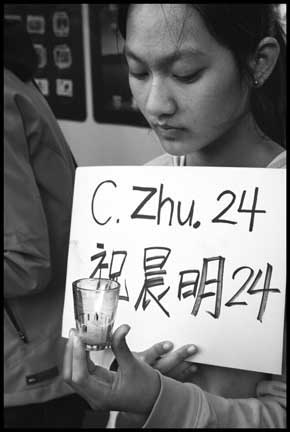

When workers started committing suicide at Foxconn, protestors held signs with their names in front of Apple’s flagship store, demanding better conditions. But the strategy employed by most large manufacturers is not to improve the conditions that kill workers. They are especially unwilling to recognize workers’ unions that would act as monitors and enforcers of signed agreements guaranteeing livable wages and safety procedures that wouldn’t put lives at risk.

Instead, the big label companies “helped spawn an $80 billion industry in corporate social responsibility (CSR) and social auditing,” according to a new report by the AFL-CIO, “Responsibility Outsourced.”

“Yet the experience of the last two decades of ‘privatized regulation’ of global supply chains has eerie parallels with the financial self-regulation that failed so spectacularly. . . ” That CSR industry, the report charges, “helped keep wages low and working conditions poor, [while] it provided public relations cover for producers.”

One corporate CSR auditing firm, the Business Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI), had certified two factories in Rana Plaza, New Waves Style and Phantom Apparel. The web site of another factory, Ether Tex, said the same firm had audited it, as well, and that it had also passed inspection by a second corporate auditor, the Service Organization for Compliance Audit Management (SOCAM).

The BSCI web site admitted auditing the first two, but disclaimed any responsibility for the deaths of hundreds of workers in the premises it had certified. “The reasons of the collapse of the factories seem to be related to the poor infrastructure of the Rana Plaza building,” it said. “BSCI focuses on monitoring and improving labour issues within factories and relies on local authorities to ensure the construction and infrastructure is secure.”

BSCI was set up by the Foreign Trade Association, a company group based in Europe “in order to create consistency and harmonisation for companies wanting to improve their social compliance in the global supply chain,” its web site says. SOCAM was created by the huge C&A clothing manufacturer, based in the UK and Germany.

The global proliferation of sweatshops has driven the income and working conditions of garment, electronics and other factory workers to the absolute rock bottom. Half a century ago, their conditions were much better. After the huge organizing drives of US workers in the 1930s and ’40s, a critical mass of garment workers in the United States belonged to unions – enough so that workers’ wages afforded them a secure and decent life. Most worked directly for manufacturers. And when those companies began to use contracting shops, workers’ organized strength enabled them to force employers to agree to critical measures that protected their jobs.

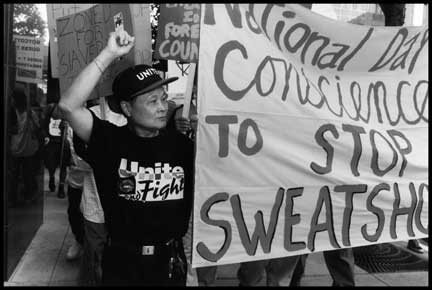

San Francisco garment workers and their union, UNITE, protest the closure of the city’s garment factories, and the relocation of work to sweatshops in Asia and Latin America. (Photo: David Bacon)As the new AFL-CIO report relates, the key was the “jobbers agreement.” Each manufacturer or brand could only place orders with union contractors, which were guaranteed steady work to keep workers permanently employed. No new contractor could be used unless existing ones had a full supply of orders. And the manufacturers had to give the contractors a high enough price to guarantee the union wages.

San Francisco garment workers and their union, UNITE, protest the closure of the city’s garment factories, and the relocation of work to sweatshops in Asia and Latin America. (Photo: David Bacon)As the new AFL-CIO report relates, the key was the “jobbers agreement.” Each manufacturer or brand could only place orders with union contractors, which were guaranteed steady work to keep workers permanently employed. No new contractor could be used unless existing ones had a full supply of orders. And the manufacturers had to give the contractors a high enough price to guarantee the union wages.

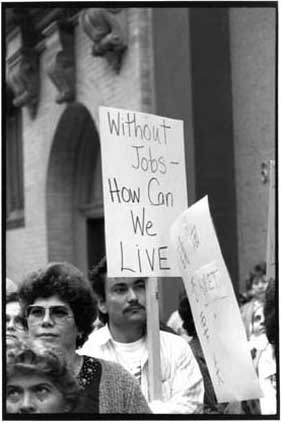

Then the bottom fell out, as US brands first closed their own factories and then began searching the world for the countries and contractors that would produce garments at the lowest possible cost. Unionized garment workers in San Francisco and other cities protested those closures, pointing to the huge difference between their wages and conditions and those in the sweatshops to which the work was transferred. The same process took place in Europe. Today, the world looks completely different as a result.

“Manufacturing work has left countries in which there were laws, collective bargaining and other systems in place to reduce workplace dangers,” the report charges, while “jobs instead have gone to countries with inadequate laws, weak enforcement and precarious employment relationships.”

This transition was aided by negotiation of corporate-friendly trade agreements guaranteeing the products of these factories unfettered access to US and European markets, while simultaneously putting pressure on developing countries to guarantee the rights of foreign corporate investors and a corporate-friendly environment of low wages, lax enforcement of worker protections and attacks on unions.

Perhaps the building codes at Rana Plaza were not enforced and permits never even obtained because Sohel Rana, the building’s owner, is reportedly active in Bangladesh’s ruling party, the Awami League. At Tazreen, the company was cited by fire inspectors, but never forced to install safety equipment.

San Francisco garment workers protest the closure of the Koret factory, and the relocation of its work to sweatshops in Central America. (Photo: David Bacon)But Bangladesh’s development policy is based on attracting garment production by keeping costs among the world’s lowest. Safe buildings that don’t collapse or trap workers in fires raise those costs. So do wages that might rise above Bangladesh’s 21 cents per hour – not a livable wage there or anywhere else.

San Francisco garment workers protest the closure of the Koret factory, and the relocation of its work to sweatshops in Central America. (Photo: David Bacon)But Bangladesh’s development policy is based on attracting garment production by keeping costs among the world’s lowest. Safe buildings that don’t collapse or trap workers in fires raise those costs. So do wages that might rise above Bangladesh’s 21 cents per hour – not a livable wage there or anywhere else.

The beneficiaries of those costs are the big brands whose clothes are sewn by the women in those factories. They give production contracts to the factories that make the lowest bids. Factories then compete to cut costs any way they can.

The “Responsibility Outsourced” report analyzes key experiences to support its conclusion. At Ali Enterprises, for instance, one of the two CSR giants, Social Accountability International, subcontracted with an Italian firm, RINA. “In Pakistan, RINA hired local firm RI&CA, which certified Ali Enterprises in August 2012. For two years, RINA had supervised by phone and through meetings outside Pakistan. Nearly 300 workers died in a fire two weeks after the certification,” the report charges.

Use of the CSR process goes beyond garment factories, it shows. At the Dole plantations in the Philippines, the company (with the help of the Philippine military) replaced the union organized by the workers, Amado Kadena-National Federation of Labor Unions-Kilusang Mayo Uno, with a company union. At the same time Dole had a seat on the SAI board of directors and received its SA8000 certification. Afterward, wages fell, and Dole began replacing permanent workers with temporary ones.

Chinese immigrant protestors lined up in front of Apple’s flagship store in San Francisco, holding signs with the names of workers at the Foxconn factory who committed suicide because of the working conditions. (Photo: David Bacon)At the immense Foxconn plant in China, according to the report, “when its brand’s reputation was endangered by worker suicides, deadly accidents and unrest at factories, it decided to use the FLA (the Fair Labor Association, the other pro-corporate CSR giant). After receiving a $250,000 membership fee, FLA inspected the Foxconn factories, initially praising Foxconn in the press before even completing the inspections, then issuing a moderately critical report, then insisting a few months later Foxconn was well on its way to solving its labor rights problems. Little changed for the workers, however. When 1,000 struck at a Foxconn plant in 2013, “observers reported that riot police, water cannons and physical violence were used to suppress the strikers.”

Chinese immigrant protestors lined up in front of Apple’s flagship store in San Francisco, holding signs with the names of workers at the Foxconn factory who committed suicide because of the working conditions. (Photo: David Bacon)At the immense Foxconn plant in China, according to the report, “when its brand’s reputation was endangered by worker suicides, deadly accidents and unrest at factories, it decided to use the FLA (the Fair Labor Association, the other pro-corporate CSR giant). After receiving a $250,000 membership fee, FLA inspected the Foxconn factories, initially praising Foxconn in the press before even completing the inspections, then issuing a moderately critical report, then insisting a few months later Foxconn was well on its way to solving its labor rights problems. Little changed for the workers, however. When 1,000 struck at a Foxconn plant in 2013, “observers reported that riot police, water cannons and physical violence were used to suppress the strikers.”

In 2008, Russell Athletics closed a plant in Honduras after almost 2,000 workers organized a union and began trying to bargain a contract. The FLA declared that the closure was motivated by normal business reasons. Fortunately, in this case, the workers reached out to the Workers Rights Consortium, a monitoring group set up by United Students Against Sweatshops. Threatening to hold demonstrations at US college campuses to torpedo sales of Russell sportswear, the WRC was able to get the plant reopened and the workers rehired.

This tactic was pioneered in the 1990s when USAS helped workers defeat beatings and a pro-company union at a Mexican garment plant, Kuk Dong. USAS forced Nike to step in to require its contractor respect workers’ rights. This use of consumer power in market countries, organized by anti-sweatshop students and unions, is a form of solidarity that has begun to develop a track record in making real improvements on the ground for factory workers.

The “Responsibility Outsourced” report concludes by looking at other alternative models that can improve working conditions. It points to global framework agreements between global union federations and multinational companies as particularly effective. “Because they are not unilateral, but are negotiated by workers, they represent progress over corporate codes [and] contain binding commitments by companies to respect international labor rights and national laws.”

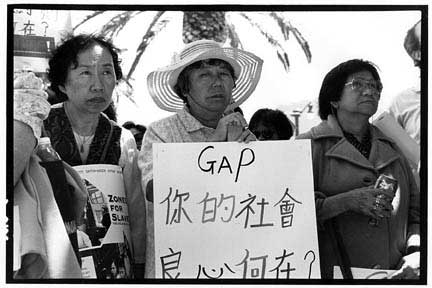

Chinese immigrant garment workers in San Francisco protest the sweatshop conditions of workers in the Gap’s contract sweatshops in Central America and Asia. (Photo: David Bacon)Some national measures passed by the US Congress are another means to progress in this area, the report finds, including the Dodd-Frank Act, which reformed financial practices on Wall Street. In Europe, it points to the protocol on freedom of association signed by Indonesian trade unions with multinational sportswear brands, backed by IndustriALL, the European labor federation.

Chinese immigrant garment workers in San Francisco protest the sweatshop conditions of workers in the Gap’s contract sweatshops in Central America and Asia. (Photo: David Bacon)Some national measures passed by the US Congress are another means to progress in this area, the report finds, including the Dodd-Frank Act, which reformed financial practices on Wall Street. In Europe, it points to the protocol on freedom of association signed by Indonesian trade unions with multinational sportswear brands, backed by IndustriALL, the European labor federation.

The WRC and USAS have developed a Designated Supplier Program, in which participating universities only buy garments from brand-name manufacturers that pay prices to contractors that can support living wages and where workers have the right to organize. Following the Tazreen fire, a binding agreement was developed by IndustriALL, the WRC and other labor NGOs. It seeks to prevent more fires by guaranteeing workers’ right to organize and enforce safety conditions. Some companies, including PVH and Tchibo have signed on. Walmart and Sears, however, not only refused, but would not even pay compensation to the Tazreen fire victims.

Finally, the report also mentions the potential impact of using the $11 trillion in workers’ pension funds, invested in corporate stock, as leverage to get companies to change their conduct. At the same time, it casts a skeptical eye on more corporate-friendly programs like Better Work and on the idea of reforming the employer-sponsored CSR process.

Ultimately, concludes Sharan Burrow, general secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation, “it is through freedom of association and organizing unions that workers have the best chance to defend their interests.”

Thank you for reading Truthout. Before you leave, we must appeal for your support.

Truthout is unlike most news publications; we’re nonprofit, independent, and free of corporate funding. Because of this, we can publish the boldly honest journalism you see from us – stories about and by grassroots activists, reports from the frontlines of social movements, and unapologetic critiques of the systemic forces that shape all of our lives.

Monied interests prevent other publications from confronting the worst injustices in our world. But Truthout remains a haven for transformative journalism in pursuit of justice.

We simply cannot do this without support from our readers. At this time, we’re appealing to add 50 monthly donors in the next 2 days. If you can, please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly gift today.