The American Dream of upward mobility is dead, thanks to the neoliberal ministrations of capital and government. But a new dream could rise from the mess left by globalization, off-shoring and austerity.

The continuation of the economic crisis of 2008 up to the present has driven home a social trend that has been evident since the late 1970s, the decline of what is usually called “the middle class” and the accompanying American Dream.

The American Dream is the belief that if you work hard, if you are blessed with at least a modicum of ability and have a little luck, you can succeed. That is, you can rise in society no matter how humble your origin to something better in the way of material well-being, economic security, a settled life and social prestige. It is the dream of upward mobility for oneself, or at least for one’s children.

As Richard Wolff has pointed out in Capitalism Hits the Fan: The Global Economic Meltdown and What to do About it, this upward mobility was a reality for most citizens of the United States for several generations, from 1820 to 1970. For 150 years, real wages rose. In the quarter century from 1947 to 1973, average real wages rose an astounding 75 percent. But that shared prosperity came to a halt in the mid ’70s. In the next 25 years, from 1979 to 2005, wages and benefits rose less than 4 percent. The sustained rise in standards of living had been made possible by a conjunction of historical circumstances, circumstances that began to reach exhaustion by the mid 1970s.

Post WWII prosperity was based on 1. the global economic dominance of the United States; 2. pent up consumer demand from the depression and war years; 3. supportive social programs; 4. some political clout due to a strong union movement that could demand a share of the prosperity; and 5. Keynesian stimulus (military spending, infrastructure development like the interstate highway system, etc.).

Fixing an Overaccumulation Crisis

By the mid 1970s, an overaccumulation crisis emerged, reflected in stagflation, which is simultaneous inflation and lack of economic growth. There were insufficient places to profitably invest all the surplus capital that had accumulated during the years of prosperity. The situation was set forth with unusual candor by former IMF Director Jacques de Larosière. In a 1984 policy address, he said:

Over the last four years the rate of return on capital investment in manufacturing in the six largest industrial countries averaged only half the rate earned during the late 1960s. . . . Even allowing for cyclical factors, a clear pattern emerges of a substantial and progressive long-term decline in rates of return on capital. There may be many reasons for this. But there is no doubt that an important contributing factor is to be found in the significant increase over the past 20 years or so in the share of income being absorbed by compensation of employees . . . This points to the need for a gradual reduction in the rate increase in real wages over the medium term if we are to it restore adequate investment incentives. – Quoted by William I. Robinson in “A Theory of Global Capitalism: Production, Class, and State in a Transnational World”

In other words, in order to ensure “adequate” profits to capital, workers’ incomes had to be curtailed.

The policies that made this suppression of incomes possible came to be called neoliberalism, a public ideology represented by President Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in England. It involved a withdrawal of government from directing the economy, leaving it instead to market forces. This meant deregulation, privatization of the commons and free trade. And that required weakening the collective hand of workers by an assault on unions and social benefits so as to strengthen the hand of capital.

“Free trade” policies of our political elite were a key part of the neoliberal offensive against labor. Trade agreements like NAFTA promoted the export of entry-level jobs to low-wage countries of the global South. With globalization, beginning in the 1980s, those entry-level industrial jobs that had made mobility into middle-income levels possible were the first jobs to be sent offshore, where they could be performed by low-wage workers in the Third World. For instance, hourly compensation costs in manufacturing (wages plus benefits) amount to $1.50 or less in China, compared with $33.50 in the United States. The Economic Policy Institute has recently calculated that in the last decade alone, US trade with China has cost us 2.7 million jobs.

Globalization was “the fix”

The globalization of capital was the fix that was found for the crisis of overaccumulation. Investment was sent abroad to low-wage areas of the global South where goods could be produced cheaply and then sold to higher-income consumers in the North. By 2008, 48 percent of all sales by the top 500 US corporations were items produced abroad, as can be readily verified by looking at the “Made in . . .” labels on clothing, electronics, automobiles and myriad other consumer goods. Even more ominously, opportunities for investment were opened up by free-trade agreements like NAFTA and later the World Trade Organization (WTO). At the same time, the bargaining power of US labor was curtailed by capital’s threat to move production abroad along with a government-endorsed campaign against unions. This restored corporate profits, but stagnated working Americans’ wages. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) now reports that the United States has the lowest rate of upward mobility of all industrialized countries. It is even seeing downward mobility.

Witness the decline in entry level wages. From 2001 to 2008, entry-level pay for high school graduates declined by 4 percent. For college graduates, the decline was 7 percent. For example, when my son graduated in computer networking from a community college in 1997, his first job was with Sylvan learning Center. Fifteen years later, his son graduated from a university, and a classmate got the very same job – at exactly the same salary of $37,000! Allowing for inflation, Sylvan now gets a university graduate for less than it used to pay for a graduate of a two-year program.

In recent decades, the economy has grown, and there was a gain in total wealth. But where did it go? From 1983 to 2008, total GDP grew from $6.1 trillion to $13.2 trillion in constant 2005 dollars. The unequal distribution of the total wealth gain during this period is revealing. The wealthiest 5 percent of American households captured 81.7 percent of the gain. The bottom 60 percent of households not only failed to share in the overall increase, they suffered a 7.5 percent loss. Some of what the top 1 percent gained came directly from that bottom 60 percent.

Downward Mobility

Between 2001 and 2008, entry level wages declined 7 percent for college graduates and 4 percent for high school graduates. Entry into middle-level incomes is becoming more difficult.

Previously it had been possible for a young man just out of high school to get a good-paying unskilled job in a unionized factory, buy a house in the suburbs, with a federally-insured mortgage, and send his kids to college with government-supported student loans. This was a common road to the success promised in the American Dream. Millions achieved that coveted upward mobility. Under the illusion they were no longer working-class, they thought of themselves as a new class in the middle, somewhere between the poor and the rich – a middle class. It is neoliberal globalization that has now blocked that road for more and more people. For the first time in generations, the next generation has a lower standard of living than their parents.

Entry point to the middle class

With the offshoring of manufacturing, the industrial regions of the northeast and the Great Lakes were transformed into a Rust Belt. United States manufacturing employment peaked in 1979 at almost 20 million and fell under neoliberalism to about 11.5 million in 2010. Today, 80 percent of the world’s industrial workforce is now in the global South. Most of it used to be in the United States. This is in no small measure the result of corporate policies over the last 30 years – policies encouraged by our political leaders – to offshore those low-skilled industrial jobs that used to be the entry point to the middle “class” for many. That may create the conditions for middle “classes” in Brazil and China, and even in Mexico, but it shrinks the middle “class” in the United States, pushing people’s living standards downward. Basically, capital is destroying the middle “class” at home and reconstituting it in parts of the global South.

As less-skilled industrial jobs were offshored, at first, in the ’90s, we were told by Robert Reich, labor secretary in the first Clinton administration, that to remain competitive in the global economy, US workers needed to upgrade their skills. We were told the new economy would be the new road to the American Dream. We are still being told that. But offshoring of jobs has not been limited to low-skilled assembly line work. Corporate capital has discovered that any job that can be done by computers can be done anywhere in the world and consequently will be done wherever the cheapest workers with the requisite knowledge can be found. So the knowledge-economy jobs are now also being offshored to countries like India. The knowledge workers there will work for far less than in the United States. And many of our college graduates today are saddled with heavy debt and unable to find work.

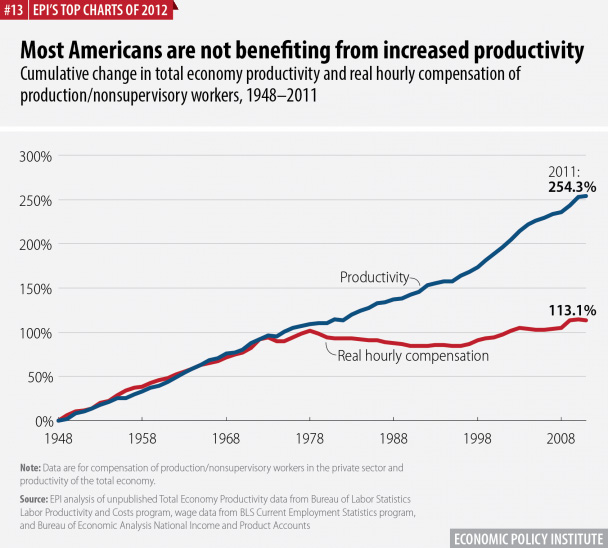

As a result of public and corporate policies, there has been wage stagnation for the past 30 years, even as worker productivity rose sharply. This is shown clearly in the following graph.

Capital took the bulk of productivity gains (shown by the upper pink line) over the 1993-2006 period by holding wages down (shown by the lower blue line). But then with the 2008 financial crisis, median family income declined further, by nearly 10 percent. Overall, as incomes have declined, corporate profits have soared.

For a while, wealth appeared to increase for average citizens because of inflating real estate values. But the financial crisis of 2008 wiped out that fictitious wealth. Median family wealth in 2010 was the same as it had been 20 years earlier.

It is important to understand that the undermining of the American Dream came at the hands of capital and government working in collusion. It is corporate capital’s unquenchable thirst for profit and political leaders’ eagerness to assist them that is destroying that dream. It is not blind economic forces operating with the inevitability of natural law, but the conscious policies of CEOs and political leaders that replace upward mobility with downward mobility. Political leaders, Democrats and Republicans alike, embrace Charles Wilson’s adage that “what’s good for General Motors is good for America.” What truth might once have been embraced by this identification of the national interest with corporate interest has long since been invalidated by the globalization of capital.

This is a central point in my book Recreating Democracy in a Globalized State. Corporate-led neoliberal globalization has transformed nation-states into what I call globalized states, that is, states that serve the interests of transnational capital above the interests of national populations. This tendency is strong in both states of the global North, like the United States, and global South, including Mexico. This has resulted in a limitation of sovereignty and of the possibility for democratically-shaped national policies. Increasingly, the countries’ fates depend more on powerful transnational corporations rather than on their own people.

Support for neoliberalism bipartisan

In the United States, there has long been bipartisan consensus behind globalization and the neoliberal policies that promote it. Both parties have long embraced basic public policies that undermine the economic security of millions of working people. This is fully substantiated by Jeff Faux in his new book The Servant Economy: Where America’s Elite is Sending the Middle Class. He argues that “the elites are unanimous: Lower everyone’s wages and standard of living – except they don’t say it out loud.” Both parties favor no-strings Wall Street bailouts, expanded unregulated trade, weakened unions and fiscal austerity as an economic priority, with its concomitant shredding of social programs. There may be some difference in degree on these issues, but both parties are in basic agreement. As Faux points out, “The mantra of both candidates is ‘Jobs, jobs, jobs.’ What they leave out is they are unwilling to confront the power of Wall Street and the Pentagon; job growth in America now depends on driving labor costs lower and lower to attract business investment.”

One-third of all working families are now poor; their annual income, for a family of four, is below the $45,622 poverty threshold – an income insufficient to meet basic needs.

This bipartisan consensus is illustrated by Senate approval this last year of free-trade agreements with Colombia, Panama and South Korea. While all politicians were calling for more jobs, they approved a free-trade agreement that they knew would destroy jobs. This was evident in the fact that approval of the free-trade agreement was accompanied by extended unemployment benefits for displaced workers. It’s like they just can’t help themselves when an opportunity arises to favor transnational corporations. And now the Obama administration is set to expand this folly even further with the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

An Economic Policy Institute study shows that increasing wage inequality is the result of deliberate and reversible policy decisions. “Ever since [around 1978], each administration and Congress have made choices – expanding trade, deregulating finance and weakening welfare – that helped the rich and hurt everyone else. Inequality didn’t just happen. . . .The government created it,” said Larry Michel, institute president.

As we have seen, the result of these policies is that wages have been stagnant for the last 30 years and now are even declining. Faux projects that “by the mid-2020s we can expect about a 20 percent drop in the real wages of the average American who has to work for a low or moderate standard of living.” Corporations have put US workers into competition with low-wage workers in China, Mexico and other areas of the global South. And this has happened with the full support of our political leaders. They all seem intent on realizing NYT columnist Thomas Friedman’s vision of a flat world, The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century, i.e. a world where globally high-income earners are brought down to a lower level and those at the bottom rise up some, resulting in global-income averages far below what those in the global North once found acceptable.

Meritocratic Individualism

The ironic thing about neoliberal policies is the extent to which political support for them has come from those sectors of society that have been harmed by them. This was most pronounced when in the mid-1990s conservatives took control of the House of Representatives under the leadership of Newt Gingrich. Their contract on America called for dismantling the very social programs that had facilitated the upward mobility achieved by the white suburban voters who had elected them to office. How are we to understand this strange phenomenon – people voting against the very programs that had enabled them to realize the American Dream?

What exactly is this dream? It takes many forms for different groups at different historical moments. As we have seen, underlying them all is the dream of achieving the good life by individual upward mobility through one’s own effort. This dream is based on the perception that the society offers the opportunity for such mobility so that it is up to the initiative of the individual to seize these opportunities and make something of himself. The idea that one can “make something of oneself” is the mark of an achievement-oriented society. This is a society in which social status and rewards are not ascribed by birth or membership in a particular group, but are instead achieved by virtue of one’s own talent and efforts. Thus social success is seen as merited, something that the individual has earned. It is a meritocratic individualist dream. The key elements of the American Dream then are: 1. meritocratically 2. achieved status through 3. individual 4. effort where 5. opportunities are available. The formula for individual success is then “talent + effort + luck = success.”

However, one of the factors that the American Dream tends to overlook is the importance of social institutions that support these efforts and thereby make the success of individuals possible. These institutional supports may be provided by the community, by a social group or class, or by the state. But it is through them that the larger society nurtures its members. Meritocratic individualism tends to blind us to these social supports, enabling individuals to then give full credit to themselves for their successes. It is precisely this blind spot that leads many to disown the very social supports that enabled their success. They don’t think about the federally ensured mortgages that made it possible for them to buy that house in the suburbs, the federal highway program that made it feasible to live far from where they work, the union that won better pay for their job so they could afford to move out of the city, the student aid programs and the university itself that provided an educational opportunity and prepared them for better jobs. And I could go on and on with the list of social supports that undergird the lifestyle of the middle classes: the health system that keeps them alive, the food standards programs that protects against unsafe food, the occupational safety and health agencies that protect them against unsafe working conditions, the social security program that lifts the burden of supporting elderly parents from the shoulders of young families and offers them some financial security in their own old age, etc., etc. Indeed, there are myriad ways that are not fully appreciated in which society supports its members. So a more complete formula would be “talent + effort + luck + social supports = success.”

The fact that the importance of social institutions is downplayed in the meritocratic individualist ideology has two effects. 1. Those who have benefited from those supports tend to deny that benefit, thinking that it will taint the merit of their accomplishments, and 2. It tends to undermine political support for the very institutions we need to support us. It leads to the self-congratulatory belief that “I built this myself,” to quote the Republican mantra in the recent campaign. The once-comfortable suburbanites failed to realize that it is not only the poor who benefit from social programs, but they themselves as well. That they have been blind to this is due to their own meritocratic individualistic ideology that can understand outcomes only in terms of individual effort and talent. This opened the way for what has now been a three-decade-long offensive by the right against social programs and government itself, leaving our fate in the invisible hand of “the market,” resulting in the end of the American Dream.

The Usefulness of Middle Classes

It is generally accepted that large, prosperous middle classes or middle strata are vital to the future of the United States. There are both economic and political reasons for this. Economically, the health of capitalism requires a large sector of consumers with sufficient income to be able to buy what is produced. That is a reality that Henry Ford taught a century ago when he raised the wages of his workers so they could buy his automobiles. Without effective consumer demand, capital cannot realize profits. That is a reality that has become evident in today’s long recession. Businesses are not investing, and jobs are not being created because there is low consumer demand due to high unemployment and high consumer debt. But that then results in higher unemployment in a vicious downward spiral that is evident to all those whose perceptions are reality-based. This has been pointed out twice a week by Paul Krugman in his New York Times columns. And now the point has been made by another Nobel economics prize winner, Joseph Stiglitz in his new book on inequality. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future.

Politically, prosperous middle strata are important for stability. As the term middle “class” is usually used today, it involves an expectation of upward mobility, rising income and a comfortable and secure standard of living. It is this upward mobility that is of particular political importance. Political stability is enhanced by having a sizable sector of the population that believes it has an opportunity to improve its condition in the existing system – or at least its children do. That is why the existence of a middle “class” is widely considered to be of crucial importance for a stable democracy of the US type. It is at the heart of The American Dream.

The American Dream has been a key legitimating myth in our society. Regardless of the inequalities that exist, the injustices suffered, the sacrifices endured, the “American way of life” has been generally accepted as good by most of the population because it has been believed that it still offers the opportunity for upward mobility toward a better future. Thus this ideology has been a force for social stability. It has led many to accept the status quo, even to defend it, because of the expectation, if not the hope, that life will get better for them if they but work hard and play by the rules.

Legitimacy of systems questioned

With the growing downward mobility now being experienced, the social contract is unraveling. The legitimacy of the dominant institutions is being questioned. Public confidence in Congress as well as government is at an all-time low; large banks are viewed (correctly) as criminal; blind faith in market magic has been dispelled – and corporations are even seen as having betrayed the nation. The legitimacy of the system of capitalism is in crisis as sizable percentages now have a positive view of socialism as an alternative, particularly among the young (who have not known the rabid anticommunism of the Cold War era). As the national elections in 2008 and 2012 have shown, the people of the United States are asking for far-reaching changes, more change than the political elite is willing or even able to deliver.

If we limit our optic to the United States, even if we expand it to include the other advanced capitalist societies, the prospects for resumption of significant endogenous economic growth are dim. That has been the argument of Northwestern University economist Robert J. Gordon. In his widely discussed National Bureau of Economic Research paper, “Is U.S. Economic Growth Over?” Gordon predicts a dark future of “epochal decline in growth from the US record of the last 150 years.” The greatest innovations, Gordon argues, are behind us, with little prospect for transformative change along the lines of the three previous industrial revolutions.” It is summarized by Thomas B. Edsall, in “No More Industrial Revolutions?” in The New York Times.

Without new major innovations to offer opportunities for profitable investment, where is all the accumulated capital to go? Here again we have a classic over-accumulation crisis. One fix that has been deployed by the corporate wealthy is to reduce their tax burden, shifting it to the popular classes below. This has been the agenda of their sector of the political elite for decades. That has been combined with the neoliberal offensive against social programs, again at the expense of the popular classes. In effect, the plutocracy has come to understand that growth of their wealth will no longer come mainly from productive investment, but must come out of the hides of those below them. That requires imposing austerity on others so they can continue to prosper.

Thomas B. Edsall, author of The Age of Austerity: How Scarcity Will Remake American Politics, sums up the situation as follows:

Affluent Republicans – the donor and policy base of the conservative movement – are on red alert. They want to protect and enhance their position in a future of diminished resources. What really provokes the ferocity with which the right currently fights for regressive tax and spending policies is a deeply pessimistic vision premised on a future of hard times. This vision has prompted the Republican Party to adopt a preemptive strategy that anticipates the end of growth and the onset of sustained austerity – a strategy to make sure that the size of their slice of the pie doesn’t get smaller as the pie shrinks.

It is in this light that we can understand the death march the Republican Party has set out on. Its survival and that of its patrons is at stake. It leads them to adopt scorched-earth policies that ought to spell certain electoral defeat were it not for their gerrymandering, voter suppression, election rigging and other antidemocratic measures needed to maintain political power within the existing political duopoly. What they are so desperate to protect is not only their own political careers, but the insatiable hunger of capital.

For its part, the Democratic Party is also beholden to the interests of transnational capital, as I pointed out earlier. As Jeff Faux has documented, as early as the Carter administration, the Democratic Party embraced the neoliberal ideology. New Democrat Bill Clinton extended the Reagan-Bush I program of globalization with free trade and deregulation of finance capital. The Obama administration has continued on the same course. The political elite is united on its basic priorities. As Faux remarks, the United States is no longer rich enough to continue to finance America’s three principal national dreams:

1. The dream of the business elite for subsidized, unregulated capitalism.

2. The dream of the political elite for global hegemony.

3. The dream of the people for a steadily rising standard of living.

We can certainly continue to have one out of three, and perhaps even two out of three. But three out of three? No.

It is the dream of the US people that will have to go. That is the reality that no US politician dares to utter. If he did, it might spark popular demands that dreams 1. and 2. be sacrificed instead.

The hard truth is that none of the three can be sustained indefinitely. Capitalism is in crisis. The military costs of global hegemony have become more than a debt-burdened state can sustain, as well as more than much of the world will continue to tolerate.

As for rising living standards, even if the dreams of Wall Street and Washington did not trump those of the people, are they really sustainable? With only a small portion of the world’s population, the United States consumes an immensely disproportionate share of the world’s resources. The current rate of use of world resources globally would be sustainable if we had one and one-half planet Earths. But guess what? We have only one. And the rest of the world’s peoples also have dreams of rising standards of living. If all the people in the entire world enjoyed US standards with the same per capita ecological footprint, five Earths would be needed.

My favorite slogan from the Occupy movement was “Wake up from the American Dream. Create a livable American reality.” That is the challenge We the People face in the 21st century. And we have to face it with little help from our political elite and none from capital. We have to do it ourselves. It will take social movements and prolonged struggle. It will take courage and bold experimentation. And for starters, it will take speaking the truth: The American Dream is over. For good or ill, history will move on without it.

Postscript: Besides this dominant American Dream, there is an alternative one in the background. It has its roots in the 18th century Enlightenment and was expressed in the French Revolution with the slogan “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” That was the dream of a society in which all could live in community, a society of mutual support among equals, where each individual was free to develop his/her human capacities supported by the community. The basic values of that vision are deeply rooted in the American culture. It can be the basis of an alternative – sustainable – American Dream.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.