This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement

Edited by Leslie G. Kelen

University Press of Mississippi, 2011

Copublished with The Center for Documentary Expression and Art

251pp,/$45.00

Photography in Mexico

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

San Francisco, CA

March 10 – July 8, 2012

Can photographers be participants in the social events they document? Eighty years ago the question would have seemed irrelevant in the political upsurges of the 1930s, in both Mexico and the United States. Many photographers were political activists, and saw their work intimately connected to workers strikes, political revolution or the movements for indigenous rights.

Today what was an obvious link is often viewed as a dangerous conflict of interest. Politics compromise art. Photographers must be objective and neutral, or at least stand at a distance from the reality they record on film or the compact flash card.

Now a book and a recent exhibition have provided both images and the narrative experiences of photographers that should reopen this debate. This Light of Ours, Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement, was published recently by the University Press of Mississippi, and the exhibition, Photography in Mexico, ran at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art last year.

The book and exhibit share a common discourse about the relation between documentary photographers and social movements. The book is an intensive look at the photographers of just one movement — the civil rights movement in the U.S. south during the 1960s. The exhibit highlights the changing relationship between photographers and Mexico’s social movements from the Revolution to the present.

This Light of Ours is a beautiful collection of almost 200 black and white photographs, duo toned and reproduced in extraordinary brilliance. They were taken, not by mainstream media photographers who visited the south during the most intense moments of the upheaval of the 1960s, but by photographers who worked as part of the civil rights movement itself, especially the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. Interviews with six of the nine photographers follow the photographs.

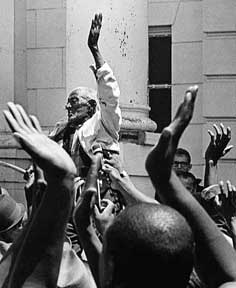

Ed Fondren, 104 years old, Bob Fitch, Batesville, Mississippi, 1966.Bob Fitch, who went on to document the farm worker movement in California after his years in the south, captures the perspective shared by these civil rights photographers and the impact the movement made on their lives. “”I did various kinds of organizing for the balance of my life and photographed those activities as I went through,” he says in his interview. “And I perceived myself as an organizer who uses a camera to tell the story of my work, which is true today.”1

Ed Fondren, 104 years old, Bob Fitch, Batesville, Mississippi, 1966.Bob Fitch, who went on to document the farm worker movement in California after his years in the south, captures the perspective shared by these civil rights photographers and the impact the movement made on their lives. “”I did various kinds of organizing for the balance of my life and photographed those activities as I went through,” he says in his interview. “And I perceived myself as an organizer who uses a camera to tell the story of my work, which is true today.”1

To Fitch, work as a photographer springs from his work as an organizer. Both are a means to fight for social and racial justice. Because he’s an organizer, he’s there when friends carry El Fondren, 104 years old, from the courthouse after registering to vote (an act which cost people their lives in Mississippi at the time). Fitch’s quick eye frames Fondren between two hands about to clap in celebration, with other hands reaching up. Like all the photos in the book, it’s a document of a critical historical moment, and at the same time an inspiration to other Black farmers to go down to the courthouse. It is also a beautiful image.2

Fitch’s organizer’s perspective does not make him less of a photographer. His portrait of Cesar Chavez was used for the U.S. postage stamp. His image of Dorothy Day surrounded by helmeted sheriffs during the Coachella grape strike became one of the best-known photographs of the early years of the United Farm Workers. But Fitch’s perspective puts him at odds with that taught in journalism schools and practiced in the mainstream media. Photographers today are expected to be “objective” observers of events, not active participants in them. In fact, participation in marches or demonstrations is held to so compromise a photographer that it is grounds for discharge at newspapers like the New York Times or Washington Post.

Matt Herron, one of the best-known photographers in the book, describes three goals for his work as a SNCC photographer: “I was a budding photojournalist, that was foremost, and that was how I was gonna support the family,” he remembers. “I was also a propagandist for the movement. When movement people wanted pictures I did it and they used them…I wanted to do social documentary work on the way of life that was southern, both black and white, and to try and document this weird culture that we’d thrust ourselves into.”3

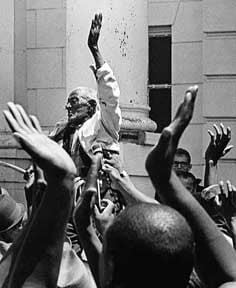

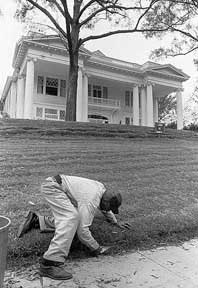

Black labor maintained white privelege, Matt Herron, Jackson, Mississippi, 1963.Herron’s photograph of a Black man clipping the lawn in front of a ante-bellum style mansion in Jackson serves all three purposes. In one image it captures the class and race relations of the south. The juxtaposition of the gardener below and the rich family above, in a composition in which the man is large and detailed enough to be real as a person, but is dwarfed by lawn and house, is a visual indictment of the lack of social equality and justice. The book doesn’t say if this image was sold, helping to make a living for his family, but Herron did have a long career as a photojournalist after his years in the south.

Black labor maintained white privelege, Matt Herron, Jackson, Mississippi, 1963.Herron’s photograph of a Black man clipping the lawn in front of a ante-bellum style mansion in Jackson serves all three purposes. In one image it captures the class and race relations of the south. The juxtaposition of the gardener below and the rich family above, in a composition in which the man is large and detailed enough to be real as a person, but is dwarfed by lawn and house, is a visual indictment of the lack of social equality and justice. The book doesn’t say if this image was sold, helping to make a living for his family, but Herron did have a long career as a photojournalist after his years in the south.

Documentary photographers today still struggle with their relationship to the communities and movements they document, and their need to make a living. His self-description probably sounds very familiar to many young photographers around the Occupy protests, who consider themselves activist photojournalists — simultaneously participants and documentarians.

The work of photographers like Fitch, Herron and their fellow civil rights activists gains visual and emotional power from their closeness to the movement they document. They are not “objective,” but partisan. For them, the documentation of social reality is part of the movement for social change. George Ballis, another photographer who went from the south to California to document the early years of the farm workers movement, explains that closeness: “Well, it’s one thing to talk about people in a condition; it’s another thing to look somebody in the eye. When I did that, I saw me, I saw we. I didn’t see them any more. I saw us. So I’m not working on their issues, I’m working on our issues. We’re all in this together, whether it’s farm labor conditions or civil rights or gay marriages or the conditions of the steelworkers, it’s us.”4

MFDP demonstrations, George Ballis, Atlantic City, New Jersey, 1964.During the Democratic Party convention that refused to seat the movement-organized Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, most press photographers shot the scenes in the hall where the confrontation took place. So did Ballis. But because he was part of the movement, later that night he was with the activists from the south as they held aloft a casket on the Atlantic City boardwalk, symbolizing the Klan murders of civil rights workers Goodwin, Schwerner and Chaney. Ballis shows the price paid for voting rights at the very moment when those rights are being denied. His ability as a photographer to take this nighttime image, using available light and no flash, renders the drama even more intense.

MFDP demonstrations, George Ballis, Atlantic City, New Jersey, 1964.During the Democratic Party convention that refused to seat the movement-organized Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, most press photographers shot the scenes in the hall where the confrontation took place. So did Ballis. But because he was part of the movement, later that night he was with the activists from the south as they held aloft a casket on the Atlantic City boardwalk, symbolizing the Klan murders of civil rights workers Goodwin, Schwerner and Chaney. Ballis shows the price paid for voting rights at the very moment when those rights are being denied. His ability as a photographer to take this nighttime image, using available light and no flash, renders the drama even more intense.

Julian Bond writes in the introduction, “Uniquely among its civil rights organizational contemporaries, SNCC employed photographers, stocked darkrooms in Atlanta, Georgia and Tougaloo, Mississippi, sent photographers to train with famed photographer Richard Avedon [!], employed photography in exceptional ways, and produced photographers who are distinguished in the field today…SNCC’s idea of photography was functional; it was to provide pictures for SNCC propaganda. Our photographers made it art.”5

Summer volunteer Jim Nance, Herbert Randall, Hattiesburg, Mississippi, 1964.Some images, like Randall’s portrait of summer volunteer Jim Nance striding up a railroad track past the “shotgun” houses of Hattiesburg’s Black community, is art and documentation both, as Bond says. The dynamism of the composition, using the perspective lines of tracks and houses to frame the walking man, give it emotional force. Nance, with his folders in his hand, is walking into a future he’s determined to create, as the neighbors look on.

Summer volunteer Jim Nance, Herbert Randall, Hattiesburg, Mississippi, 1964.Some images, like Randall’s portrait of summer volunteer Jim Nance striding up a railroad track past the “shotgun” houses of Hattiesburg’s Black community, is art and documentation both, as Bond says. The dynamism of the composition, using the perspective lines of tracks and houses to frame the walking man, give it emotional force. Nance, with his folders in his hand, is walking into a future he’s determined to create, as the neighbors look on.

Maria Varela says, “I never considered myself an artist…I had a job to do, and I couldn’t afford the luxury of being an artist…But there was a reason I was shooting in the first place…And basically the theory behind my shooting was these are strong beautiful people that are not seen in this country. They are not paid attention to. They are not icon material, you know, but here they are.” Not exactly what you learn in the photojournalism class where the pursuit of the icon, the completely self-referential image, is defined as the goal that protects the photographer’s “objectivity.” Varela says, “I knew you not only had to use the words of local people about how they did something, you had to also use pictures showing them taking leadership roles in their own communities.”6

These photographs helped set the politics of the time – they created cultural ideas that still define for us what this social movement and its era were about. None perhaps more than that of the fire hoses turned on demonstrators, captured by Bob Adelman in Birmingham in 1963. The image’s simplicity – the huge fury of the water shooting across the entire frame, and the people hit by it in one corner – gives it tremendous visual energy and power.

In Birmingham the use of firehoses and dogs backfired, Bob Adelman, Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, Alabama, 1963.These images and the interviews tell us a great deal about the relationship between the photographer and the reality she or he is documenting. By the end of the book we understand the way an activist photographer functions, and the motivation for doing this work. The photographer has to balance the tension between producing an image that “works” — that uses composition, lighting and visual techniques to create an image that resonates in the mind and emotions of the viewer — and at the same time produce an image that has is useful to the movement the photographer is trying to serve.

In Birmingham the use of firehoses and dogs backfired, Bob Adelman, Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, Alabama, 1963.These images and the interviews tell us a great deal about the relationship between the photographer and the reality she or he is documenting. By the end of the book we understand the way an activist photographer functions, and the motivation for doing this work. The photographer has to balance the tension between producing an image that “works” — that uses composition, lighting and visual techniques to create an image that resonates in the mind and emotions of the viewer — and at the same time produce an image that has is useful to the movement the photographer is trying to serve.

By presenting both the images and narratives, the book gives this work historical context. The civil rights movement helped rescue socially-committed photography from the long suffocating effects of the Cold War. The photographs not only documented a movement that helped to break the hold of the Cold War on this country’s politics, but were taken by photographers who recovered the tradition of social activism in photography of the 1930s and early 1940s.

Compare them, for instance, with two photographs taken by Otto Hegel and Hansel Mieth, activist photographers connected with the movements of dock workers and farm laborers in the 1930s in California. These two fled Germany as the Nazis gained power, and took their cameras into the huge cotton strike of 1933, and then the west coast waterfront strike of 1934. Dorothea Lange, shooting during the same period in the same area, saw herself as a documentarian of social conditions. Hegel and Mieth saw themselves as part of the movements and communities they were documenting, in the way that Ballis later described.

Night Strike Meeting at the Crossroads, Hansel Mieth and Otto Hegel, San Joaquin Valley, California, 1936.In one image, taking during a farm labor strike in California’s central valley, Hegel and Mieth use available light at night to dramatic effect, as Ballis did in Atlantic City.7 The image of the speaker is lit by headlights in the upper corner, while the men listening lean on a car or stand with hands in their pockets. The lighting and composition make it plain that the meeting is clandestine. In this era, growers used shotguns and terror to suppress union organizing and strikes. The photograph was possible only because the two were activists in the movement themselves, knew where the meeting was taking place, and were trusted enough that workers let them take the photograph.

Night Strike Meeting at the Crossroads, Hansel Mieth and Otto Hegel, San Joaquin Valley, California, 1936.In one image, taking during a farm labor strike in California’s central valley, Hegel and Mieth use available light at night to dramatic effect, as Ballis did in Atlantic City.7 The image of the speaker is lit by headlights in the upper corner, while the men listening lean on a car or stand with hands in their pockets. The lighting and composition make it plain that the meeting is clandestine. In this era, growers used shotguns and terror to suppress union organizing and strikes. The photograph was possible only because the two were activists in the movement themselves, knew where the meeting was taking place, and were trusted enough that workers let them take the photograph.

One of the best known of Mieth’s images from the 1930s showed the shapeup in which workers were hired to unload ships on the waterfront.8 At the top of the image, a man is at the window, his face is in shadow. He is the foreman who controls the jobs. In front, massed in the lower part of the image, dozens of men reach out their hands. You can almost hear them calling out – “choose me, choose me!” Anyone who’s seen day laborers cluster around a contractor’s pickup truck in front of Home Depot knows this scene is as heart rending today as it was in the 30s.

Outstretched Hands, Hansel Mieth, San Francisco, California, 1934.Mieth’s photograph was not just a document. It became a symbol to the workers of the humiliating conditions they wanted to end, as they launched what became the San Francisco general strike. It was an appeal to join the union, go on strike, and end the shapeup on the docks forever, much like Herron’s photograph of the gardener below the mansion urged people to protest racism and inequality. Perhaps it’s a testament to this image’s power that longshore workers on the Pacific Coast have had a union hiring hall, and no shapeup, ever since the end of that strike.

Outstretched Hands, Hansel Mieth, San Francisco, California, 1934.Mieth’s photograph was not just a document. It became a symbol to the workers of the humiliating conditions they wanted to end, as they launched what became the San Francisco general strike. It was an appeal to join the union, go on strike, and end the shapeup on the docks forever, much like Herron’s photograph of the gardener below the mansion urged people to protest racism and inequality. Perhaps it’s a testament to this image’s power that longshore workers on the Pacific Coast have had a union hiring hall, and no shapeup, ever since the end of that strike.

Photographers in Mexico also dealt with the same set of choices. The histories of U.S. and Mexican photography, and of our social movements, share important parallels. There a political environment grew more conservative also, limiting the development of social documentary photography, much as it did in the U.S. during the same years. The Photography in Mexico show presents an historical overview, illuminating the way the politically-inspired photography of the 1920s and 30s became less directly connected with that country’s movements for social change. However in Mexico as well, the movements of the 1960s, and more recent ones connected to displacement and migration, are reforging that connection.

Mexico’s social documentary photography begins before the show’s purview, with Agustin Casasola’s photographs of the Revolution. While many showed the soldiers and the conflict, some served to illuminate starkly the source of the conflict. One of his most famous shows the Zapatista peasant soldiers eating in the fancy Sanborn’s restaurant, served by waitresses in aprons more accustomed to attending to Mexico City’s wealthy.9 The revolution upended the old social order, and humble lost their humility and took their place at the counter of the rich, who in the photograph are nowhere in sight. Casasola didn’t really view himself at the time as a partisan of one side, but his understanding of the Revolution’s social causes gave him the insight producing the image.

Peasant Zapatistas, members of a Mexican insurgent group, are fed breakfast at the famous restaurant Sanborns, Agustin Casasola, Mexico City, 1914.The show starts in the two decades immediately after the Revolution — the same period in which U.S. photographers produced some of the best-known social documentary work — the period of the New York Photo League and the Farm Security Administration. It began with a rejection of earlier photographic trends that depicted Mexico as a land of “exotic” indigenous people, or concentrated on a European pictorialist style. The modernist critique advanced when Edward Weston and Tina Modotti arrived during the early 1920s, and Modotti in particular allied herself with the radical muralists Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros and Jose Clemente Orozco. Modotti was actually born in Italy and raised in San Francisco. In Mexico City she pulled herself out of Weston’s shadow, and became much more overtly political, putting her photography at the service of the Mexican Communist Party and the country’s then-leftwing government.

Peasant Zapatistas, members of a Mexican insurgent group, are fed breakfast at the famous restaurant Sanborns, Agustin Casasola, Mexico City, 1914.The show starts in the two decades immediately after the Revolution — the same period in which U.S. photographers produced some of the best-known social documentary work — the period of the New York Photo League and the Farm Security Administration. It began with a rejection of earlier photographic trends that depicted Mexico as a land of “exotic” indigenous people, or concentrated on a European pictorialist style. The modernist critique advanced when Edward Weston and Tina Modotti arrived during the early 1920s, and Modotti in particular allied herself with the radical muralists Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros and Jose Clemente Orozco. Modotti was actually born in Italy and raised in San Francisco. In Mexico City she pulled herself out of Weston’s shadow, and became much more overtly political, putting her photography at the service of the Mexican Communist Party and the country’s then-leftwing government.

Mexican sombrero with hammer and sickle, Tina Modotti, Mexico City, 1927.While she produced a body of documentary work, she also took photographs specifically intended to advance her goal of inspiring leftwing political consciousness, and connecting it to Mexican nationalism, which was being redefined in the postrevolutionary years. In one image, she marries the traditional Communist hammer and sickle to a sombrero like those worn by the Zapatistas, almost saying that the ideology is, or can be, Mexican.

Mexican sombrero with hammer and sickle, Tina Modotti, Mexico City, 1927.While she produced a body of documentary work, she also took photographs specifically intended to advance her goal of inspiring leftwing political consciousness, and connecting it to Mexican nationalism, which was being redefined in the postrevolutionary years. In one image, she marries the traditional Communist hammer and sickle to a sombrero like those worn by the Zapatistas, almost saying that the ideology is, or can be, Mexican.

Bandolier, corn, guitar, Tina Modotti, Mexico City, 1927.Next she abandons the hammer and sickle themselves, and produces an image using Mexican cultural and revolutionary symbols – the ear of corn, the guitar, and the bandolier. Both images show her deep knowledge and mastery of photographic technique. Modotti eventually defied the modern paradigm that would have activists give up their politics to pursue their art, by giving up photography entirely, and going to Spain during the Spanish Civil War to evacuate the refugees of fascism.

Bandolier, corn, guitar, Tina Modotti, Mexico City, 1927.Next she abandons the hammer and sickle themselves, and produces an image using Mexican cultural and revolutionary symbols – the ear of corn, the guitar, and the bandolier. Both images show her deep knowledge and mastery of photographic technique. Modotti eventually defied the modern paradigm that would have activists give up their politics to pursue their art, by giving up photography entirely, and going to Spain during the Spanish Civil War to evacuate the refugees of fascism.

The show continues with the photographs of Manuel Alvarez Bravo, who became a photographer during the cultural and political ferment in which Modotti was active. The exhibition including his “Death of a Striker,” showing the violence of the social turmoil of the time,10 but Alvarez Bravo was not a political militant or activist/photographer as Modotti was. In a long career he combined documentary work, surrealism, nude photography and other genres. His first wife, Lola Alvarez Bravo, also became a pioneer documenting the country’s indigenous cultural roots, using a realist style to combat “exoticism”.

Another U.S.-born photographer who spent her life in Mexico, and became an important figure in Mexican graphic arts and photography was Mariana Yampolsky. She became the first woman in the Taller de Grafica Popular (the People’s Graphic Workshop), an anti-fascist project started in the late 1930s by Leopoldo Méndez, Pablo O’Higgins and Luis Arena.

Martel, Mariana Yampolsky, Mexico, 1968.Yampolsky was a socialist, close to the Mexican Communist Party, and worked for many years with the Secretariat of Public Education, during the period when it was staffed by progressive educators dedicated to bringing schools and literacy to rural, especially indigenous areas. One print of a fat man squeezing blood from a worker is titled “Monopoly knows how to squeeze the last cent from the worker.”11 She published art and children’s’ books, including textbooks for schools, and documented life in indigenous communities in a realist style, influencing Graciela Iturbide and Flor Garduño.

Martel, Mariana Yampolsky, Mexico, 1968.Yampolsky was a socialist, close to the Mexican Communist Party, and worked for many years with the Secretariat of Public Education, during the period when it was staffed by progressive educators dedicated to bringing schools and literacy to rural, especially indigenous areas. One print of a fat man squeezing blood from a worker is titled “Monopoly knows how to squeeze the last cent from the worker.”11 She published art and children’s’ books, including textbooks for schools, and documented life in indigenous communities in a realist style, influencing Graciela Iturbide and Flor Garduño.

One of the most well-known photographs in this exhibition, Martel, shows a disused railway state, half a railroad car, empty tracks leading to nothing in the distance.12 The composition has the strong graphic elements that show her skill as a printmaker, paring reality down to just a few stark elements. It dates from the years when passenger rail service still existed in Mexico, long since gone, yet it is evocative of the migration issues of today. She said, “People interest me. If I have to define my photography, I’d say my studio is the street.”

But as radical social movements in Mexico were either co-opted by the government or repressed, the ability of photographers to maintain links to them also weakened. While in the U.S. some leftwing photographers, like Mieth and Hegel, were blacklisted and lost access to mainstream media, in Mexico an increasing conservatism slowly broke the link between photographers and radical unions and political parties.

Despite this, Mexican photographers continued to use photography to document the bitter social reality underlying official optimism. The work of Nacho Lopez, Hector Garcia and others rebelled against depicting either false cheer or the exploitation of indigenous pre-Hispanic cultures as exotic fare for Europeans and tourists. Lopez famously remarked that “Photography was not meant as art to adorn walls, but rather to make obvious the ancestral cruelty of man against man, the greatness of his love for things and everyday things.”13

Trabajadores, Hector Garcia, 1950s.Hector Garcia, who died last year at 89, also tried to use photography as a way to help dissident social movements break through the wall of official silence. He became active in the 1930s, talking photographs of social protests in which he also participated, even starting a newspaper that carried his images of student marches. One striking image from the exhibition shows two welders. Their dark glasses, and cloth wrapped around their noses and mouths are the only protection from fumes and sparks.

Trabajadores, Hector Garcia, 1950s.Hector Garcia, who died last year at 89, also tried to use photography as a way to help dissident social movements break through the wall of official silence. He became active in the 1930s, talking photographs of social protests in which he also participated, even starting a newspaper that carried his images of student marches. One striking image from the exhibition shows two welders. Their dark glasses, and cloth wrapped around their noses and mouths are the only protection from fumes and sparks.

In 1958 he covered the Mexican railway strike, which led to the imprisonment of its leaders Demetrio Vallejo and Valentin Campa. When muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros was imprisoned in 1960 at the height of Mexico’s anti-Communist purge, Garcia took a famous image showing him with his hand raised, behind the bars of the Lucumberri Prison.14 “What I’ve done practically all my life,” he explained, “is to be a witness and to make graphic testimonies of the movements and struggles of the social classes in Mexico. This continues to be the most important motive I have to do photography.”15

Iturbide herself, who later became known for images of indigenous culture, especially Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas, shown in the exhibition, had roots in photography connected to the political left. In 1973 she went to Panama to take photographs of General Omar Torrijos, the radical who finally ended U.S. control over the Panama Canal. “I’d been invited by people close the Communist Party to participate in a Peace Congress that was going to take place there…I’d just begun my work as a photographer, and at that time I was especially interested in showing aspects of indigenous culture.”16 She began a series of trips to Panamanian rural communities, and a relationship with Torrijos that ended when he died in a mysterious plane explosion. Her work documenting indigenous culture eventually won worldwide recognition.

La Nuestra Senora de las Iguanas, Juchitan, Oaxaca, Mexico, Graciela Iturbide, 1979.Eventually, however, the link between photographer and social movement became as difficult in Mexico as it was in the U.S. But then students were shot in Tlatelolco Plaza in 1968 (just shortly after the years documented in This Light of Ours). The event shocked Mexican society in ways similar to seeing marchers attacked by dogs and fire hoses in the U.S. south. Many of the country’s progressive photographers had their outlook forged by that event and what followed. Exhibitions of photographs, like that of the students stripped in front of soldiers after the massacre, still travel through Mexico.

La Nuestra Senora de las Iguanas, Juchitan, Oaxaca, Mexico, Graciela Iturbide, 1979.Eventually, however, the link between photographer and social movement became as difficult in Mexico as it was in the U.S. But then students were shot in Tlatelolco Plaza in 1968 (just shortly after the years documented in This Light of Ours). The event shocked Mexican society in ways similar to seeing marchers attacked by dogs and fire hoses in the U.S. south. Many of the country’s progressive photographers had their outlook forged by that event and what followed. Exhibitions of photographs, like that of the students stripped in front of soldiers after the massacre, still travel through Mexico.

Students arrested at Tlatelolco, Press photograph, 1968.The exhibition passes over many of the photographers and images of this generation, however, like Pedro Valtierra, who founded the important Mexican photography magazine Cuartoscuro. Realism is represented by the huge aerial urban landscapes of Pablo Lopez Luz, the documentation of the excesses of the wealthy by Yvonne Vanegas and Daniela Rossell, or the wrestlers of Lourdes Grobet.17 But it is a more distant kind of realism, less connected to the movements for social change that have swept Mexico in the last few decades.

Students arrested at Tlatelolco, Press photograph, 1968.The exhibition passes over many of the photographers and images of this generation, however, like Pedro Valtierra, who founded the important Mexican photography magazine Cuartoscuro. Realism is represented by the huge aerial urban landscapes of Pablo Lopez Luz, the documentation of the excesses of the wealthy by Yvonne Vanegas and Daniela Rossell, or the wrestlers of Lourdes Grobet.17 But it is a more distant kind of realism, less connected to the movements for social change that have swept Mexico in the last few decades.

In the last salon, the images of the phenomenon that has shaped Mexican consciousness today more than almost any other — the migration of 11% of it people north of the border — are mostly from U.S. rather than Mexican photographers. That might have been an opportunity to present documentation arising from the concentration of Mexicans in the U.S., and the enormous debate over the status and rights of immigrants. While the African American civil rights movement had specific issues arising from the history of Black people that are different from those affecting Mexican immigrants, the demand for social equality gives them a lot in common. A new generation of indigenous Mexican photographers, including people like Leopoldo Peña and Miguel Bravo, now work on both sides of the border, as do U.S. photographers like David Maung, Fred Lonidier, Francisco Dominguez, myself and fortunately a number of others.

Instead of documenting the migrant rights movements in both Mexico and the U.S. (with its parallels to the civil rights movement a generation earlier) the signature piece for this section of the exhibition is a huge photograph of the border wall between the U.S. and Mexico, a distant desert panorama in which the migrants themselves are strangely absent.18

Today debate over the mission of documentary photography and its content has often taken a back seat to discussion of its form and technique. Yet many of the pioneering photographic techniques of the last century were made by socially-committed photographers looking for new ways to capture the imagination of their audience. Many were migrants themselves — refugees from Germany and Europe, like John Guttman, or Mieth and Hegel. They sought to break the staid rules of artistic composition, sharpness, and angle to cause viewers to question their assumptions. Like playwright Bertoldt Brecht, they were disciples of realism, committed to class partisanship and showing social reality from the bottom up. But they also often used a stylized technique that would not allow viewers to relax in comfort. Their use of the camera had a point to make, a critique. As Garcia says, it was not meant to adorn walls.

The social crisis of our time calls for a similar redefinition of what photography can and should document. Missing from mainstream U.S. photography is not so much the depiction of shocking social reality, but the sense that society can be changed, and a vision of what that change might be. Documentary photography is no longer didactic. It is detached, and the photographer looks at the contradictions, and sometimes the hypocrisy, from a distance.

This Light of Ours, and the historical context presented by Photography in Mexico show us an alternative — engagement and social commitment, practiced by photographers in different periods on both sides of the border. They not an exercise in nostalgia, but should provoke a discourse among documentary photographers about the content of work, and its relationship to the social movements of our time. Today’s movements are complex — perhaps it’s harder to find the sense of political certainty that animated the vision of Tina Modotti or Otto Hegel and Hansel Mieth. But racism is still alive and well. Economic inequality is greater now than it has been for half a century. People are fighting for their survival.

And it’s happening here, not just in safely-distant countries half a world away.

NOTES 1. Leslie Kelen, ed: This Light of Ours (University Press of Mississippi, 2011) p. 228. 2. Ibid, p. 120. 3. Ibid, p. 234. 4. Ibid, p. 226. 5. Ibid, p. 15. 6. Ibid, p. 221-2. 7. Hansel Mieth and Otto Hegel, Night Meeting at the Cross Roads, 1936. 8. Hansel Mieth, Outstretched Hands, 1934. 9. Agustin Casasola, Peasant Zapatistas, members of a Mexican insurgent group, are fed breakfast at the famous restaurant Sanborns, 1914. 10. Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Obrero en Huelga Asesinado, 1934, 11. Mariana Yampolsky, Monopoly knows how to squeeze the last cent from the worker, lithograph, 1949. 12. Mariana Yampolsky, Martel, 1968. 13. quoted by Blanca Ruiz, “Travesias / Muestran los fetiches de Nacho Lopez” [Voyages/Exhibit the fetiches of Nacho Lopez]. Reforma, Mexico City, 1999, p. 27. 14. Hector Garcia, David Alfaro Siqueiros (El Coronelazo), Lecumberri, México, D.F., 1960. 15. quoted on the webpage of the Southwestern and Mexican Photography Collection, the Witleff Collections. 16. Graciela Iturbide, Torrijos: el hombre y el mito, Umbrage Editions, New York, 2007, p. 78. 17. exhibition: Photography in Mexico, SF Museum of Modern Art, 2012. 18. Victoria Sambunaris, Sin Titulo, from the series De La Frontera, 2010

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.