Eight national governments in the European Union have banned Monsanto’s MON810 maize and other forms of GMO cultivation in their countries: Austria, Bulgaria, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Luxembourg and Poland. In Poland, Amflora potatoes and MON810 were banned in January of this year, with the Ministry of Agriculture citing danger to bees in justifying its decision. Violation of the bans are sanctioned with fines of 200 percent of the value of GM seeds, with government ordinance to destroy any GMO fields.

The struggle for the ban took several years and involved a coalition of actors. Greenpeace Poland produced a movie revealing conflict of interest and attempts by biotech giants like Monsanto to influence politicians. In September of last year, Warsaw activists protested in front of the American Embassy against Monsanto, which has an estimated 3,000 hectares of MON810 cultivated in Poland — though the actual amounts planted are hard to determine because farmers purchased some GMO products in the Czech Republic.

In its history, the European Union has only approved two genetically modified organisms for cultivation: Monsanto’s MON810 maize, in 1998 (which was renewed in 2009), and BASF’s Amflora potatoes, in 2010 (although the latter has not been widespread and the company is withdrawing from the market). There are currently over 100,000 hectares of GMO cultivation in the 27 E.U.-member countries, and the main country with MON810 crops is Spain, which increased its cultivation by 19.5 percent last year. Again, the data are based on industry declarations to the government, meaning the actual figures could vary as much as 80 percent.

Monsanto wields its E.U. power from an office in Brussels where it tries to influence public decision-making processes to increase company profits, according to Koen Roovers of Alter-E.U, which is cooperating with Combat Monsanto and Corporate Europe Observatory to encourage more transparency in the biotech sector. Corporate Europe Observatory, Earth Open Source, Testbiotech and other NGOs revealed that the higher ranked employees of the European Food Safety Authority, which evaluates products for authorization, have been linked to Monsanto and other GMO producers. In May 2012, the European Parliament pointed to this conflict of interest in the EFSA and postponed the E.U. budget approval as a result.

But the power of E.U. states against GMO authorization have grown, with Italy announcing in April of this year that it wants to introduce a ban as well, following the insistence of its Minister of Health. UK-based organization GM-freeze calculated that Italy’s rejection of GMO crops would have a major impact because “in terms of voting at the Council of Ministers, Italy’s decision to join the countries banning the GM crop now makes it very difficult for the [European] Commission to take any action to lift the bans, because the nine Member States have 162 votes out of the 345 total, which means a qualified majority against the bans (255 votes) is impossible to achieve.” The countries with a GMO ban represent 56 percent of the total E.U. population.

Even while an official ban on GM crops is still absent in most of the E.U. member states, regions and municipalities have taken initiative to define themselves as GMO-free zones: in Belgium (entire Wallonia), Finland, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the UK, regional GMO bans are widely in place.

Such GMO-free zones are particularly notable in Spain, the main GM producer in the E.U., where 30 percent of crops are GMO. In Catalunya, the country’s wealthiest region, MON810 accounted for 90% of seedlings. While MON810 is grown in Catalunya’s neighboring province Aragón, four regions — Asturias, Basque Country, Balearic Islands and Canary Islands — have declared themselves GMO-free. The provinces of Málaga, Álava and Vizcaya as well as the islands of Menorca, Mallorca and Cabildo Insular de Lanzarote have declared their territories GMO-free. In total, 117 Spanish municipalities in 14 regions have sided against GMOs, representing about 20 percent of the country’s population.

GMO Research and Industry Blowback

Professor Gilles-Eric Séralini at the University of Caen in France has been a victim of attacks for revealing that Monsanto products lead to health problems. In 2011, he won a libel case against the French Association for Plant Biotechnology and its president, Marc Fellous. Then, in September of 2012, Séralini demonstrated in a two-year study of rats fed with NK603 maize, that either with or without the use of the herbicide Roundup, a higher frequency of tumors, kidney and liver pathologies were detected. EFSA gave a green light to this maize based on studies over a 90-day period. Monsanto has since waged a heavy PR campaign in an effort to discredit Séralini’s findings, although the French Minister of Agriculture, Stéphane Le Foll, has stressed that long term studies on GMOs are necessary and that evaluation and control at the European level should be improved.

What is perhaps most surprising about Séralini’s research is not the result, but who funded it. Large retailers have supported the project financially; in the wake of mad cow disease scandal, French authorities created additional supervisory bodies for food security, and as a result, traceability of food has improved. Distributors there have also become more accountable for the products they sell. One of the main participants in the effort has been Gérard Mulliez, fouder of Auchan, one of the world’s largest retailers. Several dozens donors also created the association CERES, which gave half a million euros to start Séralini’s experiments.

Another alliance for counter-expertise on GMO in Europe has been in the form of Partnerships Between Institutions and Citizens for Research and Innovation (Partenariats entre Institutions et Citoyens pour la Recherche et l’Innovation), or PICRI. This kind of partnership, inspired by similar practices in Canada, strives to increase access and involvement in the research of GMOs for citizens and civil society. The Future Generations association also communicates research and findings about GMOs to the public, an effort that will increase transparency of GMO evaluations, according to Christian Vélot who is working at the Université Paris-Sud 11.

Battle-crop Fields

The distance required between GMO cultivation and neighboring farms in some countries is an additional burden for development of GM fields. While the internal E.U. rules are relatively strict, there are inconsistencies in the regulations applied to foods grown in E.U. countries and identical imported products, making it more difficult to grow than import them.

On the activist front, a field liberation movement engaged in tearing up GM crops has been active in Spain. Some 8,000 Spanish citizens mobilized in a protest against GMOs in Zaragoza in 2009, and 15,000 people in Madrid in 2010. Voluntary Reapers (faucheurs volontaires) is a decentralized network of activists who have undertaken civil disobedience by mowing down GMO fields in France since the end of the 1990s.

On March 26, eight voluntary reapers (one of them, the renowned farmer José Bové, who is a Member of European Parliament) were fined for tearing up Monsanto’s MON810 and NK603 maize experimental cultivations, which had already been banned by the French government in Civaux and Valdivienne, in central western France, since a 2008 ruling by the Council of State which deemed the fields illegal. Now, Bové and others are being asked to compensate Monsanto to the tune of 135,700 euros for the crop damage. The voluntary reapers intend to reverse the decision in the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

But the struggle has also involved some individual victims. On April 22, a voluntary reaper named Pierre Azelvandre took his life. In 2009, Azelvandre had destroyed fields of transgenic grapevines cultivated by the French National Institute for Agricultural Research in Colmar, Alsace. His actions were followed, in August of 2010, by 60 activists and 15 farmers tearing up dozens of hectares of GMO grapevines, for which they received two month suspended prison sentences.

The Power of Bad Opinion

In general, consumers in the E.U. do not support GM products, Eurobarometers show. In Portugal, where the GM crop fields are relatively widespread, only 59 percent of people have even heard of GMOs, and in Spain the number is just 74 percent, according to data from 2010. In contrast, in Germany 95 percent of people knew about GMOs; in the E.U. overall, the average was 84 percent.

However, among those who know what GMOs are, 59 percent of surveyed citizens believe they are unhealthy, with only 22 percent believing they are not. Greece (85 percent), Germany (74 percent) and France (62 percent) revealed strong majorities of the population were afraid of the health effects from GMOs. What’s more, 89 percent of UK shoppers have said they want labels placed on food produced from GM-fed animals, and 72 percent said they are willing to pay slightly more to be informed about the GMO content of what they’re eating.

Already, four French, four British, one Italian and one Irish retailer have introduced labels for GMO-free meat and dairy products. The withdrawal of GM potatoes produced by German multinational BASF from the E.U. market is another victory. The company explained its decision stating it had insufficient support among politicians and consumers for GM products in the E.U., and will be moving its GM plant science headquarters from Germany to Raleigh, North Carolina.

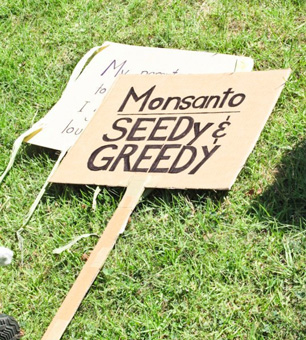

On Saturday, March 25, a mass turnout by European nations will join the global March Against Monsanto.

Mónica Parrilla from Greenpeace Spain contributed to this report.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.