(Image: Doctor and stethoscope via Shutterstock)As major provisions in the Affordable Care Act are rolled out, we’ll need a way to track its effectiveness – a scorecard for “Obamacare,” as it’s now universally called. What’s the best way to do that?

(Image: Doctor and stethoscope via Shutterstock)As major provisions in the Affordable Care Act are rolled out, we’ll need a way to track its effectiveness – a scorecard for “Obamacare,” as it’s now universally called. What’s the best way to do that?

The US lags behind the rest of the developed world by virtually any reasonable measure, including rates of illness, mortality, life expectancy, overall cost, access to care, overall economic impact, and the household cost of care.

Here are some initial forecasts,using reports and statistical databases from the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) as a baseline, which we’ll revise as more data becomes available.

Cost/Effectiveness

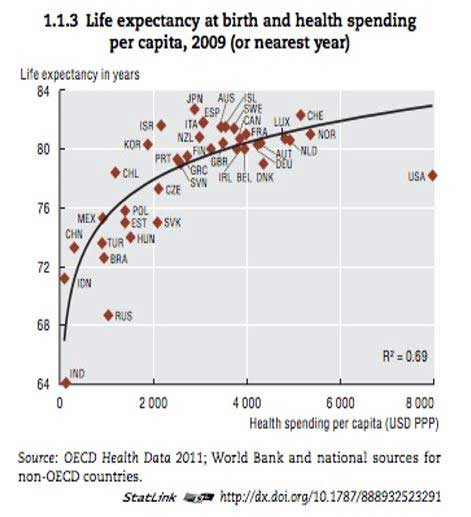

This graph illustrates the US healthcare system’s striking variance from other countries in terms of cost effectiveness. (If you’re not into graphs, we’ll tell you afterwards what it shows):

The US is all the way to the right because we spend much more for healthcare than any other developed country. We’re not at the top because people in some of those countries live much longer. Theye’re getting much more bang for their buck – or yen, or peso, or shekel, or euro – than we are. So what do all these countries have in common?

A national health insurance system.

Impact on the National Economy

Healthcare as a Percentage of the GDP

Healthcare costs in the United States currently consume 17.6 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), compared with an average of 9.6 percent for all developed nations. In other words, medical care costs nearly twice as much in the US as in other developed countries.

Health care spending contributes to the GDP. But a dollar spent in health care doesn’t create as many jobs as a dollar spent on education, mass transit, or rebuilding our failing infrastructure. And a health care dollar which is passed through private insurance companies is even less effective at creating growth and employment.

How much is Obamacare likely to help?

It should “bend the cost curve,” slowing the rate of increase somewhat – by improving the actuarial mix of people enrolled in health plans, enacting some regulatory deterrents to future increases, and encouraging other cost management measures.

But nobody’s arguing that Obamacare will lower costs, only that it will slow future increases. And its favorable actuarial effect depends on large numbers of young people choosing to pay insurance premiums rather than incur a tax penalty.

What’s more, its regulations are under political attack. And many of the innovations encouraged under the law have been tried before in other forms.

Per-Person and Household Cost of Care

Americans paid $7,960 per year for health care as of the last OECD study, more than twice the $3,233 average for other developed countries. These costs, like nationwide costs, have been rising much more quickly than in other countries.

The OECD studied personal health spending for people with both above- and below-average income and found that costs for both groups were higher here than in any other nation studied.

Overall rates of increase have slowed somewhat in recent years. But, as discussed in Part 1 of this series, the out-of-pocket cost for families has been rising much more quickly than inflation. And, as discussed in Part 2, the “Cadillac tax” on high-cost plans is likely to make that trend even worse.

How much is Obamacare likely to help?

The fact that more people will have health insurance should, at least in theory, eventually reduce the per-person cost for people with insurance. That should slow the rate of premium increases. But the “Cadillac tax” is already increasing out-of-pocket costs. We’ll be watching, but it seems clear that families will still see burdensome increases in the cost of their care.

An Observation

If we could bring US health spending in line with those other countries – the ones with national health insurance – it would add more than a trillion dollars to the US economy every year.

Coverage and Access

The Uninsured

An estimated 45 million Americans were uninsured in 2008.

How much is Obamacare likely to help?

It should help significantly, although not as much as originally predicted. The PPACA is estimated to cut that figure by sixty percent, according to the Urban Institute, which would still leave an estimated 18 million people uninsured.

Access to Care

Americans see a physician four times per year on average, one-third less than the overall average of 6.4 per year for developed countries.

How much is Obamacare likely to help?

Insurers in the California health exchange, the most advanced in the country, report that far fewer doctors will be available to people that enroll through the exchanges. But many more people will have insurance, which should help improve this figure.

System Effectiveness

Health Status

Life expectancy at birth in the United States is 78.2 years, compared with 79.5 years in other developed countries. (Japan’s life expectancy is 83 years.) US expected lifespan is, in fact, the shortest of any among the countries we normally think of as “developed.”

Our infant mortality rate is 6.5 deaths per 1,000 live births, half again as high as other developed countries (a category which includes newly-developed nations like Turkey and Russia).

Some of these figures are due to wealth and health inequity in the United States. African-American infant mortality has historically been 2.5 times that of white Americans, for example.

How much is Obamacare likely to help?

The law’s expected to contribute to an overall improvement in Americans’ health status. The law will increase Medicaid enrollment, which should help underserved populations, although Republican Governors are stonewalling this aspect of the law (along with most of the others). It also gives latitude to the states in implementation, which could hamstring efforts significantly.

We’re hopeful on this one, but we’ll need to track it and see.

Overtreatment

Americans with health insurance are also subjected to many more medical procedures than necessary, according to studies, because of a basic flaw in our “system.”

The way we pay physicians and facilities gives them an incentive to both overtreat and overbill, which can be seen in the utilization statistics: Use of MRI scanners in the US is more than twice the average for developed nations. The US has an average of 213 knee replacements per 100,000, compared to the OECD average of 116. Cardiac surgeons performed 377 coronary angioplasties per 100,000 people her, double the OECD average of 188.

Studies show strong geographic variation in the rates of US cardiac surgeries, regardless of patient demographics or health status. The primary difference was the number of cardiac surgeons per person in each region. (See the Dartmouth Atlas of Cardiovascular Health Care.)

Our expensive educational system makes the problem worse. One analysis suggested that student debt influences many new doctors’ choice of specialty, especially among middle-class medical students.

How much is Obamacare likely to help?

The law attempted to address some of these issues, but has been hamstrung by demagoguery about “death panels.” It’s also limited by its reliance on private health insurance companies. (A “public option” would have allowed public and private systems to compete, with potentially far-reaching effects.)

In our opinion, expectations for the law’s experiments in provider compensation are overly optimistic – but, as in all areas, we’ll be watching and tracking with an open mind.

Private Insurance Companies

Profit Margins

Health insurance remains highly profitable in the US, especially for the larger carriers. In 2012 the five largest US carriers earned $12.2 billion in aggregate profit. Even at inflated US costs, profit margins for these companies alone could have insured nearly 1.5 million people.

Insurers often understate their real profits by including the cost of medical care in their expenses. A more accurate measure includes only those costs that are directly related to the operation of the insurance business. By this measure, they’re extremely profitable. These margins drain tens of billions of dollars, and perhaps considerably more, from the US healthcare economy every year.

How much is Obamacare likely to help?

The bill does include an amendment which limits profits to 15 percent of premiums, but we easily identified five potential work-arounds for writer David Dayen in 2010 and they’re still valid today.

Market Concentration

A study by the American Medical Association showed that 94% of state health insurance markets could be deemed “highly concentrated” under Justice Department guidelines. The study found that:

- A single carrier had 70% or more of the market in more than a third of the areas studied.

- More than 16% of the areas were monopolized by a carrier with 90% or more of the market.

- Most US healthcare regions, in fact, are monopolies or “duopolies” (with two dominant sellers).

This lack of competition reduces or eliminates any incentive to provide better service, and enables large insurers like Wellpoint to post enormous profits ($2.7 billion total annual profits, a 38 percent annual increase in 4Q 2012).

How much is Obamacare likely to help?

The law encourages competitive financial arrangements, but these provisions aren’t likely to have much impact.

Predatory Underwriting

The best way to maximize profits in a non-competitive market is through selective underwriting, sometimes called “cherry-picking,” which targets younger and healthier populations and excludes or limits individuals or small groups with a history of illness or injury.

One of the most aggressive forms of predatory underwriting is ‘rescission,’ in which a policy is retroactively canceled after a high-cost claim is filed. In one notorious case Wellpoint targeted women with breast cancer for rescission. This practice is illegal, but insurers have found ways to evade the law. The most common move is to claim afterwards that there was deceit on the application.

How much is Obamacare likely to help?

A lot, if properly enforced. But there gaps and risks. Rescission, for example, will still be permitted in cases when coverage was fraudulently applied, which lends itself to potential abuse. Overall rate increases which are deemed “unreasonable” will be subject to Federal review, but there is no clear evidence what effect this will have on insurers.

Bureaucratic insurance-company interference

All insurance companies include a “managed care” or “medical management” function, where nurses and other paraprofessionals working under a Medical Director’s direction review requests for high-cost treatment. The concept was originally sound, at least in theory, but most have become “denial factories” which excessively reject or delay needed care.

Market concentration makes that easier. Doctors and other health providers are up against a powerful, often monopolistic force, which leaves them relatively powerless.

How much is Obamacare likely to help?

It’s not clear it will help much at all.

Conclusion

We’ll be updating this “scorecard” as its provisions take effect, but one thing’s already clear: While the law does some good things, it will only marginally improve upon a fundamentally broken system.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.