Among the world’s major nations, documents the UN agency dedicated to labor matters, only one currently has a level of inequality both high and rising.

It is well known that the level of income inequality stretches much higher in the United States than in the other developed countries of Europe and North America. Now a report from the International Labour Organization shows that U.S. inequality has literally gone off the chart.

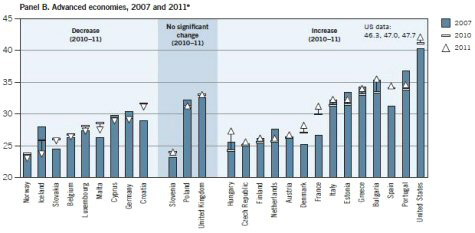

Income inequality in the United States is soaring so high, in fact, that the authors of the ILO’s new 2013 World of Work report couldn’t even place the United States on the same graph with the other 25 developed countries their new study examines.

Income inequality reflects the sum total of all the differences between the incomes enjoyed by different households in a country. Differences between rich and poor households, rich and middle-income households, middle-income and poor households all enter into total income inequality.

Researchers usually measure income inequality using a statistic called the Gini coefficient. The Gini coefficient runs from a minimum of 0 (perfect equality in incomes across all households) to 100 (one rich household gets all the income for an entire country).

The ILO report places the US Gini coefficient at 47.7, or almost half way toward the extreme where one rich household gets everything and everyone else gets nothing.

By comparison, the levels of inequality in the other 25 developed countries studied all fall in a band between 20 and 35.

Even worse, in America inequality is not only high but rising. The Unites States is one of only three developed countries where income inequality rose during the recession of 2008-2009, then continued rising through the lackluster recovery of 2010-2011.

The other two: Denmark and France. Both these countries had much lower levels of inequality to start with. By 2011, Denmark’s inequality had risen into the high 20s and France’s inequality into the low 30s.

In the United States inequality sat at 46.3 before the recession, moved to 47.0 in 2010, and rose further to 47.7 in 2011.

Rising inequality has hit the American middle class particularly hard. But America’s middle class decline began well before the recession hit in 2008. Every year fewer and fewer Americans qualify as middle class, and those who do have lower and lower incomes.

The share of U.S. adults living in middle-income households, the new ILO report notes, dropped from 61 to 51 percent between 1970 and 2010, and the median incomes of these households fell 5 percent.

Where has the middle class held its own in recent decades? Well, in Denmark and France, among other countries. The country with the largest middle class according to the ILO’s calculations is Norway, where about 70 percent of the population rate as middle class.

In the United States today only about 52 percent of the population can claim middle class status.

The World of Work report concludes that the middle class in the United States and around the world is suffering from “long-term unemployment, weakening job quality, and workers dropping out of the labour market altogether.” Things have been bad for a long time, but the recession has made them far worse.

The ILO, founded in 1946, now operates a specialist agency of the United Nations. The world’s employers and workers are equally represented on its governing board, alongside the representatives of 28 governments, including the United States government.

Different international organizations use different data sources for comparing inequality levels across countries. The ILO World of Work report uses raw data from the Census Bureau for the United States and from Eurostat for European countries.

All these sources agree that income inequality has widened more in the United States than in other developed countries. The ILO report finds a much larger difference than other organizations, such as the OECD. One reason for the difference: As a UN organization, the ILO is committed to using data from official sources like the U.S. Bureau of the Census and published, peer-reviewed scientific journal articles.

Other organizations like the OECD and private think tanks make their own estimates of national inequality levels using data that may not be publicly available and methodologies that may not be transparent or audited.

According to the official data compiled by the ILO and documented in the World of Work report, only South Africa and about a dozen Latin American countries have higher levels of inequality than the United States.

In nearly all of these countries inequality appears to be either stable or falling. Out of a total of 57 countries studied by the ILO, 31 developing and 26 developed, only one — the United States — has a level of income inequality both high and rising.

This simple fact — that only one nation has inequality both “high and rising” — shows that high and rising inequality is not inevitable. The rich are not winning everywhere, just as the rich have not always won in the United States.

We can have sensible policies that reduce inequality and bolster the middle class. The ILO suggests that we prioritize employment growth over budget cuts, increase public investment to make up for a lack of private investment, and raise taxes on unearned income from financial transactions.

The folks at the ILO are smart enough to understand that the reasons our governments don’t give us good, pro-people policies are not technical or economic, but political and ideological.

“Against mounting evidence,” the ILO concludes, “a fundamental belief persists in some quarters that less regulation and limited government will boost business confidence, improve access to international financial markets, and increase investment, although these results have not been evident.”

The empirical evidence says that we can reduce inequality and bolster the middle class by putting people back to work. But that will take government action. And government action is the one thing we don’t seem to have.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $22,000 by the end of today. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.