Three years ago, a single warning shot sent Marissa Alexander to prison. Last month, an appeals court overturned her conviction, ruling that the jury received flawed instructions on self-defense. Supporters are calling for the prosecutor to drop all charges rather than subject Alexander to a new trial.

As reported earlier on Truthout, Marissa Alexander, a mother of three and a survivor of abuse, had given birth to a baby girl in July 2010. The previous year, she had obtained a restraining order against her ex-husband Rico Gray. When she learned that she was pregnant, she amended it to remove the ban on contact while maintaining the rest of the restraining order.

On August 1, 2010, she and Gray were at home when Gray attacked her. “He assaulted me, shoving, strangling and holding me against my will, preventing me from fleeing all while I begged for him to leave,” Alexander recounted in an open letter to supporters. This was not the first time that he had assaulted her.

Alexander escaped into the garage but realized she had forgotten the keys to her truck and that the garage’s door opener was not working. She retrieved her gun, which was legally registered, and re-entered her home to escape or grab her phone to call for help. “He came into the kitchen … and realized I was unable to leave … he yelled, ‘Bitch, I will kill you!’ and charged toward me. In fear and desperate attempt, I lifted my weapon up, turned away and discharged a single shot in the wall up in the ceiling,” she recounted. Gray called the police and reported that Alexander had shot at him and his sons. Alexander was arrested and charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.

Alexander attempted to invoke Stand Your Ground, but a pretrial judge ruled that she could have escaped her attacker through the front or back doors of her home. In a 66-page deposition, Gray admitted to abusing all five of the women with whom he had children, including Alexander. Several witnesses, including Alexander’s daughter, younger sister, mother and ex-husband testified that they had seen injuries that Gray had inflicted on her.

The judge instructed the jury that, when considering Alexander’s self-defense plea, that she had to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Gray was committing aggravated battery when she fired. The jury deliberated for 12 minutes and returned with a guilty verdict. Prosecutor Angela Corey added Florida’s 10-20-LIFE sentencing enhancement, mandating a 20-year minimum sentence when a firearm is discharged.

On September 26, 2013, an appeals court found that the judge’s instructions regarding self-defense shifted the burden of proof from the prosecutor to Alexander. “At trial, the only real issue was whether she had acted in self-defense when she fired the gun. Because the jury instructions on self-defense were fundamental error, we reverse,” the court stated, remanding her case for a new trial. Marissa Alexander, however, remains in prison.

Mobilizing to Free Alexander

After her arrest, Marissa Alexander’s first husband, Lincoln Alexander, and her sister, Helena Jenkins, formed the Committee to Free Marissa Alexander. Shortly after her conviction, individuals in various states mobilized to form the Free Marissa Now campaign. Sumayya Fire had been working against domestic violence as an advocate, consultant, trainer and program builder for more than 20 years when she learned about Alexander’s case. “It touched my heart as an advocate and survivor of violence, to make a decision about defending yourself and get 20 years in prison,” she told Truthout. “It sends a message to women who fight back, who choose to save their lives. I could not not use my voice and my resources to help.”

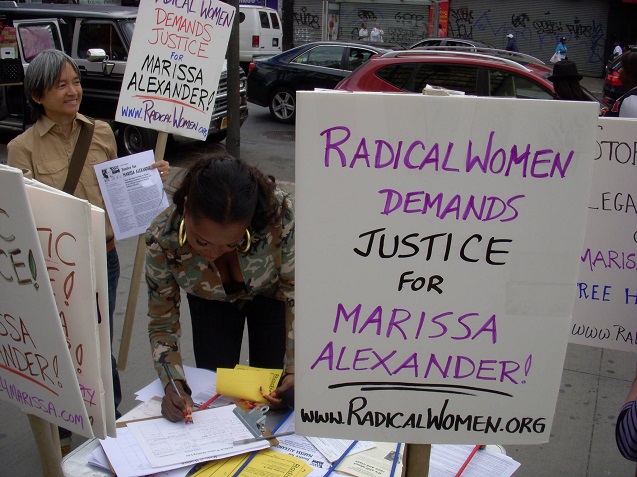

Although Fire had never organized an online campaign before, she began reaching out to those who had been organizing before Alexander’s sentencing. Radical Women and Pacific Northwest Alliance to Free Marissa Alexander was one of the first groups to respond. Lincoln Alexander referred her to Aleta Alston-Toure with the New Jim Crow Movement in Jacksonville, Florida, who had been organizing around the case.

(Photo: Victoria Law)

(Photo: Victoria Law)

Alisa Bierria, who has organized with INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence, remembered reading about Alexander shortly after her sentencing. “I connected her case with the tradition of black women organizing for their right to self-defense, including movements to free Joan Little, the New Jersey Four and CeCe McDonald,” Bierria told Truthout. She reached out to Lincoln Alexander, who connected her with Sumayya Fire.

From these connections came the Free Marissa Now mobilization campaign. The campaign attracted increased national attention after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting of Trayvon Martin. News pundits and organizers compared her case – complete with the denial of a Stand Your Ground defense – with Zimmerman’s. “The Zimmerman verdict spiked attention to Marissa Alexander overnight,” Fire said. “In one week, we had thousands of new followers on our Facebook page and hits on our tumblr. There was outrage that, in the same state, Zimmerman killed a person [and got off] while Marissa fired a warning shot and got 20 years.”

“I believe that Marissa’s case got national attention because of the timing,” Bierria agrees. But, she adds, “we have to do everything we can to keep her name out there.” She points to the 2001 INCITE! and Critical Resistance statement on the divide between the movements addressing mass incarceration and domestic and sexual violence. “There’s been a depoliticization of work to end domestic violence and sexual assault. It’s been integrated into the state’s increase in criminalization and incarceration.” A decade later, she notes, “Black women are less likely to be the symbol used to provoke organizing against mass incarceration and police brutality. Also, instead of being supported, Black women survivors of domestic violence tend to be punished by the media, their communities and institutions. We have the opportunity to highlight the connection between domestic violence and mass incarceration. We can see it clearly with Marissa, but she’s not the only survivor in prison. This is an opportunity to bring attention to all the other survivors whose names we don’t know.”

(Photo: Free Marissa Campaign)For Marissa Alexander’s 33rd birthday, on September 14, 2013, supporters across the country held events to commemorate the day and draw attention to her case. “We had birthday parties, rallies and parades,” Fire said. In addition, supporters sent Alexander cards. “Marissa received 200 cards in one day,” she recalled. “Part of our peaceful protest is to get as many people to connect with her, to let her know that she’s not forgotten.”

(Photo: Free Marissa Campaign)For Marissa Alexander’s 33rd birthday, on September 14, 2013, supporters across the country held events to commemorate the day and draw attention to her case. “We had birthday parties, rallies and parades,” Fire said. In addition, supporters sent Alexander cards. “Marissa received 200 cards in one day,” she recalled. “Part of our peaceful protest is to get as many people to connect with her, to let her know that she’s not forgotten.”

Utilizing October as Domestic Violence Awareness month, Emotional Justice Unplugged, the Chicago Taskforce on Violence Against Girls and Women, and Free Marissa Now launched a monthlong multimedia letter-writing campaign called #31forMARISSA. The campaign urges men to write letters of support to Alexander, share stories of violence experienced by women in their lives, donate to Alexander’s legal expenses, and become engaged as active allies in the domestic violence movement. Noting that men make up 25 percent of the campaign’s 14,000 Facebook followers, Fire stated that #31forMARISSA “gives men an opportunity to support the campaign and to speak out about domestic violence and sexism.”

“We are asking a nation of men – of all creeds and colors – to stand up and engage in the pursuit of freedom of a black woman,” the campaign call stated. The letters appear on the SWAGspot tumblr, which was launched in 2013 as an emotional justice community of conversations with men for men, and excerpts of the letters appear on Ebony.com daily. Each week, paper copies of the letters are mailed to Alexander.

Four Decades Earlier: Yvonne Wanrow, Self-Defense and Support

In 1972, a single shot also changed the life of Yvonne Wanrow, a mother of two in Spokane, Washington, and a Colville Native American. On August 11, William Wesler attempted to pull Wanrow’s 11-year-old son off his bicycle and drag him into his house. The boy escaped to the house of Shirley Hooper, a family friend. Wesler followed him.

Earlier that year, Hooper’s 7-year-old daughter had been raped by an unidentified person. The rape had given her a sexually transmitted disease. When she saw Wesler, the girl told her mother, “He’s the man who did it to me.” Hooper’s landlord also saw Wesler; he told Hooper that Wesler had tried to molest a young boy who had previously lived there.

Hooper called the police. Although they had previously arrested Wesler for child molestation and were familiar enough with him to nickname him “Chicken Bill,” they refused to arrest him. Instead they recommended that Hooper wait until after the weekend to file a complaint at the police station. The landlord suggested that Hooper hit Wesler with a baseball bat if he tried to enter the house. The police did not discourage the suggestion; they advised Hooper, “Yes, but wait until he gets in the house.” Hooper telephoned Wanrow, asking her to spend the night at Hooper’s home. Wanrow, a 5-foot, 4-inch woman, recently had broken her leg and was on crutches. She brought her pistol. The women also asked Angie and Chuck Michel, Wanrow’s sister and brother-in-law, to spend the night.

At 5 in the morning, Chuck Michel went to Wesler’s house with a baseball bat. He accused Wesler of molesting small children. Wesler, who was visibly intoxicated, suggested that they straighten the matter out at Hooper’s house.

Once inside Hooper’s house, Wesler refused to leave. Wanrow went to the front door to yell for Chuck Michel. When she turned and found the 6-foot-2 Wesler towering over her, she shot him.

At her trial, the judge instructed the jury to consider only what had happened “at or immediately before the killing.” These instructions omitted Wesler’s record as a sex offender. Neither Hooper’s daughter nor the doctor who had treated Wanrow’s son after Wesler’s kidnapping attempt was allowed to testify. Wanrow was convicted of murder and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

(Photo: Free Marissa Campaign)Social justice groups and organizers took up her cause, turning her into a symbol of a woman’s right to defend herself and her family from assault. Feminists in Seattle and Washington, D.C., formed Yvonne Wanrow Defense Committees, hosting events to generate public interest and raise legal funds. Women in Minnesota formed the Lesbian Feminist Organizing Committee to support her. Members of the American Indian Movement, Women of All Red Nations and the Native American Solidarity Committee organized a two-day benefit to raise money for her defense fund while educating the 200 attendees about her case, the underlying issues of violence against women, and the history of systemic violence against native people in the United States.

(Photo: Free Marissa Campaign)Social justice groups and organizers took up her cause, turning her into a symbol of a woman’s right to defend herself and her family from assault. Feminists in Seattle and Washington, D.C., formed Yvonne Wanrow Defense Committees, hosting events to generate public interest and raise legal funds. Women in Minnesota formed the Lesbian Feminist Organizing Committee to support her. Members of the American Indian Movement, Women of All Red Nations and the Native American Solidarity Committee organized a two-day benefit to raise money for her defense fund while educating the 200 attendees about her case, the underlying issues of violence against women, and the history of systemic violence against native people in the United States.

In 1977, the Washington State Supreme Court granted Wanrow a new trial, partially on the basis that the original instructions to the jury on the law of self-defense were inaccurate. The judge’s instructions had not allowed the jury to consider the relevant facts: Wesler was a known child molester; Wanrow had heard that he had previously raped her friend’s daughter; and, less than 24 hours earlier, he had attempted to assault her son. “The justification for self-defense is to be evaluated in light of ALL the facts and circumstances known to the defendant, including those known substantially before the killing,” the court declared. The court also recognized that women’s lack of access to self-defense training and to the “skills necessary to effectively repel a male assailant without resorting to the use of deadly weapons” made their circumstances different from those of men. “Care must be taken to assure that our self-defense instructions afford women the right to have their conduct judged in light of the individual physical handicaps which are the product of sex discrimination.” The decision was hailed as a landmark case for a woman’s right to self-defense.

At her 1979 retrial, Wanrow pleaded guilty to reduced charges. She received suspended sentences on the manslaughter and assault charges, five years of probation and one year of community service. Without the pressure, publicity and resources generated by her supporters, Wanrow would most likely have stayed in prison.

“We don’t want to wait to see her come out the gate”

As proven nearly 40 years earlier, support can make a huge difference. The Free Marissa Now campaign understands this and is harnessing the attention and outrage to press state officials to drop Alexander’s case rather than proceed with a new trial. “We’re hoping that letters will make a difference,” Fire said. “I just wonder if Marissa would receive a fair trial if the state already sees her as guilty and with such personal prejudgement in interviews and articles. So we are we’re asking our supporters to write e-mails and letters to encourage the state to drop the case.”

She and Bierria hope the attention and actions around Alexander’s case will lead to her freedom. “It will be through community organizing, advocacy, political education and love of self and value of our own lives that we reaffirm our right to live,” Bierria said.

We have 10 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.