Cornealious “Mike” Anderson walking out of the Mississippi County Courthouse along with his wife, LaQonna Anderson, daughter Nevaeh, 3, and grandmother Mary Porter, left, after being released from custody on May 5, 2014, in Charleston, Mo. (Photo: Jeff Roberson / The Associated Press)

Cornealious “Mike” Anderson walking out of the Mississippi County Courthouse along with his wife, LaQonna Anderson, daughter Nevaeh, 3, and grandmother Mary Porter, left, after being released from custody on May 5, 2014, in Charleston, Mo. (Photo: Jeff Roberson / The Associated Press)

The story of Cornealious “Mike” Anderson, the convicted Missouri man who, because of a state Department of Corrections error, lived free for the 13 years of his prescribed prison sentence, sparked a national debate: Should a rehabilitated man be sent to prison?

As Anderson awaited a judge’s decision about his fate, some argued he must fulfill his original sentence, while others argued he should not be responsible for the state’s incompetence and that his 13 years of good citizenship should serve as reparation to society.

On Monday, May 5, 2014, the judge declared Anderson – who has four children, owns a carpentry contracting company, volunteers at his church and coaches Little League – a “good man” and a free man.

Raj JayadevThe story of Anderson is a modern day American parable. The incarcerated man who, through mistaken or divine happenstance, was allowed to honor a promise that echoes in courtrooms every day: “Just give me the chance of freedom, and I will prove I can do good.”

Raj JayadevThe story of Anderson is a modern day American parable. The incarcerated man who, through mistaken or divine happenstance, was allowed to honor a promise that echoes in courtrooms every day: “Just give me the chance of freedom, and I will prove I can do good.”

The Anomaly of the Anderson Case

Although Anderson’s case was an anomaly, it uniquely raises a fundamental question regarding our nation’s sentencing laws. In a time of decreasing crime rates and depleted public budgets, and considering the decimation of families and communities brought about by mass incarceration and mandatory sentencing, what is the societal value of locking up people for such significant amounts of time?

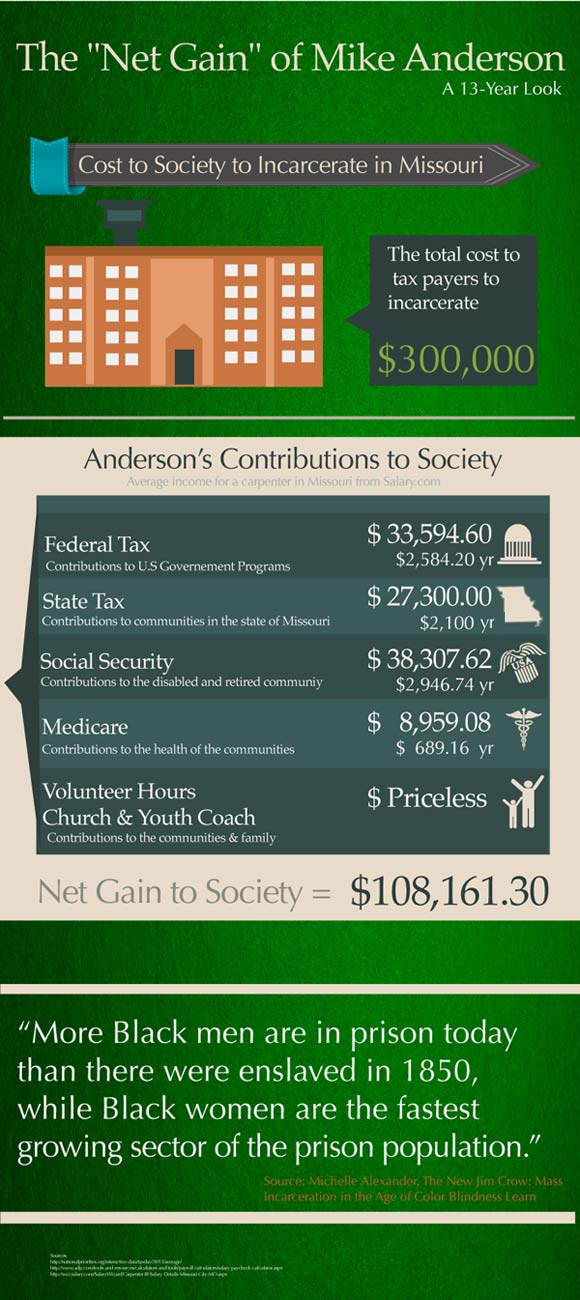

Mike Anderson offers an actual case study that not only is rehabilitation possible without a lengthy prison sentence, but that the state actually gains from limiting incarceration periods.

Empirically, the case shows nothing would have been gained by keeping Anderson in prison for 13 years; in fact, there were measurable gains by him being free during this period. He committed no crime while free and was not in the care of the state, thus absolving the state of a 13-year financial burden.

A 2012 Vera Institute of Justice study calculates that the cost of imprisoning an inmate in Missouri is $22,350 per year.

That means the clerical error that resulted in Anderson’s freedom saved the state almost $300,000, while Anderson contributed to the state and national economies as a job creator and taxpayer, and being a stakeholder in the community while creating a stable home for his family.

That means the clerical error that resulted in Anderson’s freedom saved the state almost $300,000, while Anderson contributed to the state and national economies as a job creator and taxpayer, and being a stakeholder in the community while creating a stable home for his family.

What is more telling is imagining the scenario had there been no error and Anderson had done his time in prison. Not only would the state be out $300,000 and Anderson’s loved ones, church and community have lost his contributions, but Anderson himself would have re-entered society after 13 years in prison with no job, no community or family and left only with the proven trauma of incarceration.

The irony is that the likelihood of Anderson’s re-offending would have increased dramatically if he had been in prison. Studies show the rate of re-offense for those who have come out of prison to be nearly 70 percent.

The Shifting Tide of Mandatory Sentencing

In many cases, mandatory minimum sentencing laws cause extended lockups. Had Anderson been convicted of armed robbery in my home state of California, for example, his minimum sentence would have been 12 years – a mitigated two-year sentence for the robbery charge and a consecutive 10-year sentence for the firearm.

Even if the judge had had the ability to intuit Anderson’s future positive contributions to society, with the state’s mandatory sentencing laws, he or she would not have had any discretion to remove or lessen the sentence.

Removing judicial discretion disables the common sense approach of treating each case individually and in context. What were the circumstances of the offense? What are the future prospects of the individual? What are the consequences of long-term incarceration on that person’s family? Mandatory sentences strip away those relevant questions from the decision-making process.

Click here to expand in a new window. Tellingly, these were all questions asked and considered by the Mississippi County judge this time around to decide if Anderson should be sent back to prison or be free, yet were disallowed to be deliberated on during the initial sentencing.

Tellingly, these were all questions asked and considered by the Mississippi County judge this time around to decide if Anderson should be sent back to prison or be free, yet were disallowed to be deliberated on during the initial sentencing.

As prisons have become dramatically overcrowded and government budgets stretched, some changes in mandatory sentences have been introduced. In March, Attorney General Eric Holder announced that the Obama administration is formulating new rules that would give it and the president far more latitude to pardon or reduce the sentences of thousands of drug offenders serving long federal prison sentences. In California, voters reformed the state’s three-strikes law to allow for re-sentencing of those doing life in prison for non-serious offenses.

But these steps are still incremental – and the parable of Mike Anderson plays out every day in sentencing hearings, just without the “error.” I recently interviewed a young man who was the victim of an armed robbery as part of a video that was being made for a defense attorney of the young man who allegedly committed the robbery.

The assailant, a teenager, allegedly stole the phone of the young man I interviewed, while showing a gun. We asked the victim what he thought the suspect should receive as punishment if the court found him guilty. He said roughly 80 hours of community service.

When we told him the teen was looking at 12 years’ minimum in prison – again two years for the robbery, and 10 years enhancement – the kid froze in shock. He said, “All that time for a $100 phone?” His response mirrors that of the victim in the Anderson case, who says he sees no reason for Anderson to go to prison.

No one is arguing that people should not be held accountable for their actions, but our current approach to dealing with crime is analogous to swatting a fly with a sledgehammer.

When the Prison Sentence Is the Error

Recently, I sat in court with a nervous, skinny 20-year-old named Xavier, who, that day, was to start an eight-year prison sentence.

Xavier participates in a ceremony at his church. (Photo: Jean Melesaine of Silicon Valley De-Bug)I have no doubt in my mind that his would be a story like Mike Anderson’s if he only had been given the chance. Xavier, too, would lead a positive, crime-free life, while contributing to society.

Xavier participates in a ceremony at his church. (Photo: Jean Melesaine of Silicon Valley De-Bug)I have no doubt in my mind that his would be a story like Mike Anderson’s if he only had been given the chance. Xavier, too, would lead a positive, crime-free life, while contributing to society.

He had been charged with several serious offenses. No one was killed, no serious injuries, but the numbers of potential years in prison kept stacking up. Had he gone to trial and lost, he would have been sentenced to nearly 40 years.

Xavier weighed his options and agreed to a plea deal of eight years. He has shared remorse for the day of the incident, which took place just weeks after his 18th birthday. He served a year in jail before his mother scraped the money together to bail him out during court proceedings, but California sentencing laws mandated a long-term prison commitment.

Had he been under 18, he would have likely faced months of incarceration, which is what his 16-year-old co-defendant received.

Xavier, 20, and Raj Jayadev shot hoops at this basketball court in San Jose, Calif. About a week later, Xavier started his prison term. (Photo: Jean Melesaine of Silicon Valley De-Bug)It wasn’t that Xavier and his family couldn’t make a sound argument that, if given the opportunity, he would lead a positive life without re-offending. He was in community college and was a favorite of the counselors, was a leader in his church youth ministry and, frankly, was a momma’s boy – he did everything with her.

Xavier, 20, and Raj Jayadev shot hoops at this basketball court in San Jose, Calif. About a week later, Xavier started his prison term. (Photo: Jean Melesaine of Silicon Valley De-Bug)It wasn’t that Xavier and his family couldn’t make a sound argument that, if given the opportunity, he would lead a positive life without re-offending. He was in community college and was a favorite of the counselors, was a leader in his church youth ministry and, frankly, was a momma’s boy – he did everything with her.

The day he agreed to the plea deal, we sat outside in the court parking lot with his mom. The only question he had was if he could pay the court fines before he self-surrendered so that his mom wouldn’t get the bills.

He said going to prison was like going away to college and that he would be an even better person when he came home. I doubt he believed that, but his mom was crying and he had to say something. This was a kid that really should have been going to college, not prison.

The week before Xavier turned himself in, we went and played ball. Perhaps in a state of denial or in an impulse to absorb as much of the outside world as he could before he turned himself in, he was still enrolled in his college classes, which included a basketball class. He had joked that he wanted to show off his new skills, so we went down to an outdoor basketball court.

It was dusk, that time of the day when it’s too dark to play an actual game, but just light enough to shoot around and talk.

It’s as close to sharing a meditative moment some 20-year-old guys get. We were embroiled in a classic generational debate – Jordan or LeBron at their prime – while taking ridiculous half-court shots, pretending to beat the buzzer of an actual game.

I wondered if I should bring up prison but then thought he needs this more: A memory he can hold onto – playing ball at the park.

About a week later, Xavier was on a bus to San Quentin. He will be in his late twenties when he’s let out. I don’t know what he will be like then and cannot speak to what he may have to endure while in prison.

About a week later, Xavier was on a bus to San Quentin. He will be in his late twenties when he’s let out. I don’t know what he will be like then and cannot speak to what he may have to endure while in prison.

I asked him the day he turned himself in what he needed from us, the people who supported him, and, glancing at his mother, he said, “Look after her.”

It’s not that an offense committed by Xavier, or Mike Anderson, is to be glossed over, but rather that taking away from judges – the people we elect to make such calls – the consideration of what these people may become makes little sense.

Knowing the stories of the individuals, families and communities affected by policy decisions can help us understand the moral complexities of those decisions. I hope Mike Anderson’s story is one that guides us out of the nonsensical abyss of mandatory sentencing, a practice our country can ill afford financially, politically and morally.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.