In the four bailed-out countries of the European periphery, there is not a trace of solid evidence that the austerity / structural reforms / export-led growth approach insisted upon by the EU and the IMF has paid any solid economic or social dividends, yet it is hailed as a “success.”

Four years after the start of the euro crisis, the bailed-out countries of the eurozone (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain) [1] are still facing serious problems, as the austerity policies imposed on them by the European Union (EU) authorities and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) not only failed to stabilize their economies, but actually made matters worse; in fact, much worse: The debt load increased substantially; national output was seriously undermined; unemployment reached potentially explosive levels; a credit crunch ensued; and emigration levels rose to historic heights. Because of these highly adverse effects, the citizens in the bailed-out countries have grown indignant and mistrustful toward parliamentary democracy itself, euro-skepticism has taken firm roots and a cleavage has reemerged between north and south.

Greece was sacrificed so that the euro and the European banking system would be saved.

Still, things could not have turned out drastically different than they are, for the objective of the bailout plans as drawn up was to save Europe’s banks – and thus the euro itself – at the expense of the national economies in question. Indeed, in the case of Greece, the IMF released a report in June 2013 in which it admitted 1) that it had miscalculated the size of the fiscal multiplier and thus underestimated the negative impact of the austerity policies on the Greek economy and society, and 2) that the key idea behind the bailout plan was not to help Greece, but rather to provide a “firewall” to protect the eurozone. [2] Still, the IMF has ignored the implications of its own criticism of the Greek bailout plan and has remained stubbornly committed to the dangerous idea of “expansionary austerity” [3] and to the doctrine of neoliberal structural adjustment.

To read more articles by C.J. Polychroniou and other authors in the Public Intellectual Project, click here.

In the EU, policymakers have raised hypocrisy to an even higher level. EU Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs Olli Rehn launched an attack against the IMF for the release of its report criticizing the Greek bailout program. [4] But in early 2014, responding to a question posed by Nikos Chountis, a member of the European Parliament from the Greek Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA), Rehn confessed that “at the start of the crisis, in the spring of 2010, and for some time after that, if we had proceeded directly with the restructuring of Greek debt, we would have been facing dramatic consequences as a result of a contagion effect on other member states, as well as on the banking system in Europe.” [5] In essence, what the EU commissioner was saying was that Greece was sacrificed so that the euro and the European banking system would be saved. And, as in the case of the IMF, the EU also remains adamant in its refusal to alter course from the policies of the past that have caused such an economic disaster in the bailed-out countries of the eurozone.

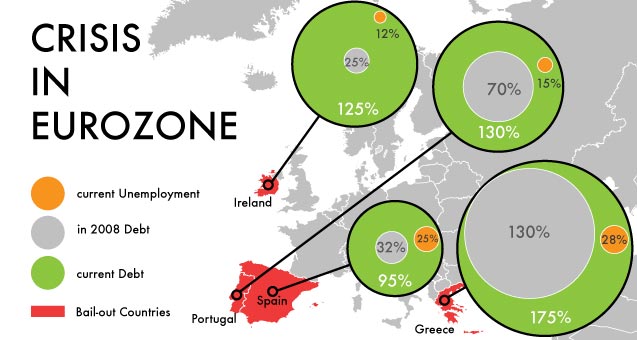

Take unemployment, for example. The current unemployment rates in the four bailed-out eurozone countries are: 27 percent for Greece; 25 percent for Spain; 15 percent for Portugal; and 12 percent for Ireland, the nation with the highest emigration rate in all of Europe, with one person leaving Ireland every six minutes, [6] and whose government is actually asking the unemployed to leave and take jobs in other European countries. [7] Yet, Ireland’s exit from the bailout program has been hailed by German Chancellor Angela Merkel herself as a “tremendous success story.” [8] In a similar display of indifference to the social catastrophe unfolding in Greece, but with the same touch of old-fashioned propaganda, the Greek prime minister, Antonis Samaras, has also described the elimination of the “twin deficits” in his country as a “success story.” [9]

Aside from some minor and ill-conceived youth employment programs, [10] which in reality serve as a distraction from the more serious problem of unemployment for older workers, the EU has done next to nothing to address the plague of unemployment. This stance, however, is consistent with the EU’s current economic mindset, a set of economic dogmas that include 1) relegating unemployment to the status of a natural and inevitable (and perhaps even desirable) outcome of fiscal adjustment; 2) relying on austerity as a confidence builder; 3) treating structural reform as a panacea; and 4) valuing exports as the primary engine of growth. [11]

Unemployment is a serious social problem because it adversely affects the economy and society as a whole while posing great risk to individuals themselves.

The four dimensions of this type of economic philosophy embraced by the EU are highly flawed and, when combined, they can be deadly dangerous. They constitute tenets of an ideological “worldview” rather than empirically proven statements. Little wonder, then, why the economies in the periphery of the eurozone are in such horrific shape, with no prospects for an end to the deep economic and social crisis that plagues millions of their citizens, until either the EU changes its policies or these nations exit the euro.

Unemployment and What to Do About It

To start with, it is simply unacceptable for EU policymakers not to have in place widespread measures to address unemployment, and to treat it instead as merely a “natural” and “inevitable” outcome of radical fiscal adjustment policies enforced in the midst of economic downturns (which all eurozone nations experienced when the global financial crisis of 2008 reached Europe’s shores sometime in 2009), where the only tangible rewards are deficit reductions at the expense of massive economic decline, greater debt accumulation and social decomposition. Unemployment is a serious social problem because it adversely affects the economy and society as a whole while posing great risk to individuals themselves, often leading to grave physical and mental health problems. Under a humanistic economic paradigm, progress would be measured not by the rate of deficit reduction but by the number of people with decent jobs and wages, while poverty and unemployment would be treated as social diseases – like tuberculosis, typhus or syphilis.

In one sense, this is the philosophy guiding an employment guarantee program or the “employer of last resort” (ELR). The fact that ELR is not even uttered in European policy circles as a possible solution for the collapsing economies of the eurozone is the best indication of how far contemporary European leadership has moved away from the mindset of the postwar social contract. Yet, the ELR proposal, as originally articulated by Hyman Minsky on the basis of the New Deal experience, [12] could go a long way toward addressing the horrific unemployment problem in the entire eurozone, which remains near record highs at 11.9 percent, with nearly half of the total made up of the long-term unemployed. [13] While Europe’s infrastructure is in much better shape than that of the United States overall, the unemployed could be put to use in a myriad of jobs in labor-intensive services, ranging from urban and environmental improvements to providing assistance to the elderly and the sick, just to mention a few of the activities that can take place in sectors of the economy where people can apply their general capabilities. The economic and social transformation that could come to pass in the periphery of the eurozone by putting millions of Greeks, Irish, Portuguese and Spaniards, as well as Italians, [14] back to work through direct employment is so immense that it boggles the mind how apathetic European policymakers are toward this large-scale, transformative opportunity.

The need for direct employment programs in the eurozone becomes even more urgent when taking into account that annual growth rates in Europe are expected to be extremely low over the next several years, ranging from 1 percent to 1.6 percent on average. [15] In other words, if slow economic growth is the “new normal” in advanced capitalist societies – as some economists such as Robert Gordon seem to believe [16] – then there is a stronger case to be made for ELR, both as a means to provide stimulus to growth and to secure full employment.

Full employment . . . is rejected today by mainstream economists and governments.

The idea of employment guarantee programs is not an invention of the 1930s. Rather, it goes way back in history, embraced by thinkers who were sensitive to the problem of the unemployed poor and concerned about the economic, social, political and moral repercussions of this state of human affairs. For example, writing in the late 18th century, Thomas Paine not only proposed a comprehensive social welfare system, but also addressed head-on the problem of unemployment and poverty that he witnessed in major cities like London by advocating a rudimentary public employment scheme that, when understood in its historical context, bears some theoretical resemblance to ELR. This is what he wrote in The Rights of Man after having described how hard and cruel life can be for the young people who come to London in search of a better life without any money:

The plan then will be: First, to erect two or more buildings, or take some already erected, capable of containing at least six thousand persons, and to have in each of these places as many kinds of employment as can be contrived, so that every person who shall come, may find something which he or she can do. Secondly, to receive all who shall come, without inquiry who or what they are. The only condition to be, that for so much or so many hours work, each person shall receive so many meals of wholesome food, and a warm lodging, at least as good as a barrack. That a certain portion of what each person’s work shall be worth shall be reserved, and given to him, or her, on their going away; and that each person shall stay as long, or as short time, or come as often as he chooses on these conditions. If each person staid three months, it would assist by rotation twenty-four thousand persons annually, though the real number, at all times, would be but six thousand. By establishing an asylum of this kind, such persons, to whom temporary distresses occur, would have an opportunity to recruit themselves, and be enabled to look out for better employment. Allowing that their labor paid but one-half the expense of supporting them, after reserving a portion of their earnings for themselves, the sum of forty thousand pounds additional would defray all other charges for even a greater number than six thousand. [17]

It is indeed important to underline that Paine’s proposal is along the lines of a job guarantee program. It represents a rejection of the prevailing attitude in Europe at the time, which favored “forced employment for the unemployed poor” [18] via the establishment of workhouses. Hence, it should also not be identified with contemporary workfare policies, which do not in general create jobs on any large scale, but seek merely to stigmatize the poor and reduce welfare payments. [19] Paine’s proposal, like Minsky’s ELR, is a jobs guarantee scheme that is voluntary and open to anyone who is ready and willing to work on a public works project for a living wage.

Full employment, defined as the condition in which every adult who is able and willing to work is actually doing so, [20] is rejected today by mainstream economists and governments. This state of affairs poses severe challenges for alternative policy prescriptions designed to do away with forced idleness, as they will automatically encounter fierce opposition by the profession and policymakers alike. [21] Returning to our discussion of the crisis in the eurozone periphery, it is abundantly clear that the EU’s stance toward growth and unemployment is aligned with the neoclassical version of economic activity, powerfully spelled out by Michal Kalecki long before the set of economic policies associated with the “neoliberal” doctrine became widespread:

Every widening of state activity is looked upon by business with suspicion, but the creation of employment by government spending has a special aspect that makes the opposition particularly intense. Under a laissez-faire system, the level of employment depends to a great extent on the so-called state of confidence. If this deteriorates, private investment declines, which results in a fall of output and employment. . . . This gives the capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: Everything that may shake the state of confidence must be carefully avoided because it would cause an economic crisis. But once the government learns the trick of increasing employment by its own purchases, this powerful controlling device loses its effectiveness. Hence budget deficits necessary to carry out government intervention must be regarded as perilous. The social function of the doctrine of “sound finance” is to make the level of employment dependent on the state of confidence. [22]

Austerity and the Confidence Fairy Tale

With the architecture of the European monetary union highly incomplete and “neoliberalism run amok,”[23] EU policymakers have been “forced” to embrace confidence, almost by default, as key to economic recovery in the bailed-out – and now unsustainably indebted – nations of the eurozone. In other words, they have come to rely more heavily on “psychological factors” by virtue of the institutional design of the monetary union itself (a “detached” central bank, lack of a treasury, no fiscal transfers) and the policies that maintain this flawed architecture (a neoliberal growth model based on fiscal austerity, exports, labor market flexibility, and privatization of public goods and services). Thus, from the start of the crisis, policymakers have maintained that austerity, combined with radical labor market reforms, would bring about confidence, which in turn would generate growth through investments and thus create new jobs that would decrease the rate of unemployment.

The international bailouts of Greece have been an unmitigated disaster for the country.

Nearly four years later, Greece, as the first “guinea pig” in the undertaking of the EU’s barbarous austerity experiment, is still waiting for the much-talked-about recovery through confidence-building austerity. In the meantime, the country’s output has been shrinking by an average annual rate of about 5.5 percent since the “rescue” plan was instituted (Greece’s GDP has shrunk by nearly a quarter since the 2008 crisis.), and unemployment jumped from 12 percent in 2010 to 28 percent in November 2013 as economic activity plummeted due to massive cuts in public spending. Small- and medium-size businesses shut down in record high numbers due to a crash in demand (domestic demand in Greece has been falling for seven consecutive years) caused largely by sharp cuts in wages and salaries and even sharper tax rate increases. As for government debt, it ballooned from slightly less than 130 percent in 2009 to 175 percent at the end of 2013 – and with a sizable “haircut” already having taken place. To add insult to injury, the best that the radical structural adjustment program and the Spartan austerity measures can promise is to reduce the Greek debt ratio to 124 percent of GDP by 2020; that is, to bring the debt-to-GDP ratio close to the levels it was at when the crisis broke out, leading to the “bailout” programs. It would not, then, be overstating the case to say that the international bailouts of Greece have been an unmitigated disaster for the country. [24]

In the rest of the bailed-out countries – Ireland, Portugal and Spain – the enforcement of harsh austerity was based on similar reasoning: Debt would be reduced and growth would be spurred if these societies proceeded with the implementation of substantial public spending cuts and adhered to an agenda of structural reforms for the purpose of making their economies more competitive. Again, the impetus for the alleged “recovery” as a result of the implementation of these measures would come through the restoration of confidence. In other words, Ireland, Portugal and Spain were also turned into “guinea pigs” for the same wild neoliberal experiment that Greece had already been subjected to with evidently disastrous results, which brings to mind a quote often attributed to Einstein: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

The effects of the austerity medicine on the other three peripheral economies of the eurozone were indeed quite devastating. [25] Take government debt ratios, which, as in the case of Greece, we were promised would be decreased through austerity. Ireland’s public debt, which stood at 25 percent of GDP in 2008, grew to nearly 65 percent by 2010 and climbed to over 125 percent by the end of 2013. Portugal’s public debt, which was slightly less than 70 percent in 2008, jumped to over 100 percent by 2011 and then to over 130 percent by 2013. And Spain’s public debt has surged to nearly 95 percent of GDP, standing at close to 1 trillion euros – three times as much as it was at the start of the crisis in 2008 – and is projected to go over 100 percent by the end of 2014. In short, the rest of the bailed-out eurozone countries are looking more and more like Greece when it comes to public debt – the result of the “voodoo” economics that the witch doctors of the EU and the IMF cooked up to formulate the so-called “rescue” plans.

Of course, the reason for the increase in unemployment rates and the public debt ratios in the bailed-out countries is because of the hard blow that the global financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent austerity policies delivered to national output and future growth prospects. History alone should have informed EU policymakers that fiscal tightening in the midst of economic downturns translates into further economic contraction. However, European policymakers not only ignored history, but also turned the idea of “growth through austerity” into a new religion. Thus, brushing aside criticism about the effects of austerity, José Manuel Barroso, president of the European Commission (EC), was bold enough to predict in early September 2011 that Europe would not enter into a recession. [26] As it turned out, the entire eurozone went into a prolonged recession that lasted nearly two years (note that the alleged “recovery” that has apparently been taking place since the middle of last year has not make a dent in the number of the unemployed) while the periphery is still mired in a virtually hopeless situation.

Austerity hasn’t worked for the bailed-out countries of the eurozone . . . when looked at from the standpoint of the impact it has had on growth, unemployment, public debt accumulation and social well-being.

Ireland, an exemplar of neoliberalism, was hit particularly hard by the global financial crisis of 2007–08, with a “cumulative nominal GDP decline of 21 percent from its peak of Q4 2007 to the trough of Q3 2010,” [27] and still has a long way to go before it reaches its pre-crisis levels of GDP and GNP (the latter is particularly relevant because of the large percentage of multinationals operating in the country). Ireland’s GDP grew at a meager 0.9 percent in 2012 and by 1.5 percent in volume terms in the third quarter of 2013, according to the Central Statistics Office of Ireland. Portugal’s GDP shrank by 3.2 percent in 2012, and by 1.4 percent in 2013. And Spain’s GDP declined by 1.4 percent in 2012 and 1.3 percent in 2013. Spain is yet another peripheral country that, according to officials, is turning the corner. This assessment seems, conveniently enough, to turn a blind eye to the jobless rate of 26 percent, expecting it somehow to vanish into thin air – perhaps because of the consequences of labor flexibility that the Spanish government is so eagerly pursuing upon the diktats of the EU and the IMF. [28]

Shrinking national outputs, increased debt loads, and unacceptable unemployment rates form, however, only part of the grim reality of economic recession in the peripheral countries of the eurozone. Because of the draconian budget cuts, vital public services have been cut to the bare bone, all while poverty has exploded, the numbers of homeless people are mounting, and inequality is growing to dangerous levels. Austerity policies have had an especially devastating effect on public health, [29] with Greece being widely recognized as experiencing nothing short of a public health tragedy [30], as a huge and still growing percentage of the population no longer has access to health care, infant mortality rates are rising, and even malaria is making a comeback. [31]

The only confidence that austerity can generate is the certainty that the future will look worse than the present,

The fact that austerity hasn’t worked for the bailed-out countries of the eurozone (or anywhere else in Europe, for that matter) is beyond dispute when looked at from the standpoint of the impact it has had on growth, unemployment, public debt accumulation, and social well-being. As for austerity reducing government deficits – which is the only “positive” thing that austerity has to show in Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain – the whole process is self-defeating because it deepens the recession, which leads to a higher debt-to-GDP ratio than before, and to higher unemployment and greater human misery. Austerity is indeed a phony solution, and the tragic experience of the bailed-out countries provides proof of that beyond a reasonable doubt.

The policy of slashing public spending, wages and salaries and raising taxes as a means of addressing high government deficits and debt when economies are experiencing severe downturns, and expecting this policy to serve as a mechanism for growth, is an easy entry into the club of “zombie economic ideas.” [32] The only confidence that austerity can generate is the certainty that the future will look worse than the present, creating a “lost generation” through depressed economies and highly unequal societies, as confirmed by a report released last year by Charita Europa, [33] with the organization going against the grain and, to its credit, making a plea for a government investment package to tackle the problem of unemployment.

(The Myth of) Neoliberal Structural Reforms as a Panacea

The intellectual case against austerity is rather easy to make because so much empirical data is stacked up against it. However, the third dimension of the EU’s current economic gestalt – deep structural reforms aligned with the neoliberal vision of economic operations – poses greater challenges due to the complexities involved in the comparison of economies with different cultural environments and institutional settings, and because, as a result, the effects of neoliberal policies have not been uniform across economies. Thus, in general, structural reforms enjoy more support even among people who seem to be rather skeptical about the benefits of austerity, although the experience with neoliberal structural reforms has been extremely negative when it comes to matters of inequality and inefficiency for many countries around the world. [34] Part of the explanation for this “anomaly” is undoubtedly due to the consolidation of neoliberalism as a hegemonic system, with neoliberalism itself having become the “central organizing principle” for the European project since the Maastricht Treaty [35], and to the fact that alternative policies for exiting the current crisis rarely receive the widespread public attention that they deserve – although in many instances they provide realistic, and perhaps the only possible, solutions for the most overburdened and unbalanced economies of the eurozone. [36]

The public in the advanced industrialized societies continued to believe in the necessity for public services and a welfare state.

First, a few comments about neoliberalism as an ideological “worldview” and the aims and objectives of the neoliberal project. The driving principles for the neoliberal approach to economy and society revolve around the privatization of public goods and services, the deregulation of markets, and the restructuring of the state into an agency that facilitates and protects unfettered capital accumulation while it shifts an increasing amount of resources from the public realm to the private sector; especially in the direction of the dominant fraction of capital in today’s advanced capitalist societies, that is, “financial” capital. The bailouts of bankrupt banking and financial institutions in the United States over the course of the latest global financial crisis, as well as of peripheral countries in the euro area by the EU authorities, need to be understood within the context of the changes that have taken place in capitalist political economy since the early 1980s, which marks the reemergence of predatory capitalism and the establishment of neoliberalism as the new institutional and ideological framework for capital accumulation on a global scale. [37]

Breaking the back of organized labor meant, of course, not only engaging in vicious propaganda, but also passing legislation making it tougher for workers to form or belong to a union and promoting policies that made employment more flexible and thus easier to manipulate and exploit.

The neoliberal project takes form and shape on account of the collapse, sometime in the mid-1970s, of the postwar structure of capital accumulation, which was based on the “fordist” model of production and government policies, which in turn were loosely based on Keynesian (or, more accurately, pseudo-Keynesian) economics. What followed was a rather distressed period of “stagflation” and a fiscal crisis of the state, [38] which prepared the ground for the resuscitation of “free market” economics. Indeed, by the early to mid-1980s, academic economists were abandoning “Keynesian” economics en masse and instead taking up the cause of promoting the virtues of neoliberal economics as articulated in the works of F. A. Hayek and Milton Friedman. Indeed, it is highly unlikely that the neoliberal (counter)revolution would have succeeded if it had not found so much support among academics, the mass media and politicians. [39] After all, the public in the advanced industrialized societies continued to believe in the necessity for public services and a welfare state. Thus the capitalist class may have been unable to have its way regarding the retreat of the social state if the intellectual elite in the United States and Europe had not themselves embraced the neoliberal vision.

From a political standpoint, the neoliberal retreat of the welfare state and the implementation of structural reforms across the economy implied not merely a victory over the realm of ideas but the defeat of those forces that stood in the way of the realization of the neoliberal vision. In practical terms, that meant debilitating the capacity of organized labor to resist structural changes favoring the interests of capital. Thus, organized labor became a direct target for the neoliberal crowd, blaming it for virtually every economic and social ill facing advanced societies. Breaking the back of organized labor meant, of course, not only engaging in vicious propaganda, but also passing legislation making it tougher for workers to form or belong to a union and promoting policies that made employment more flexible and thus easier to manipulate and exploit. To be sure, in nations like the United States and Great Britain, under the reigns of neoconservative leaders like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, respectively, a vicious class war was initiated against labor – a war that, by the mid-1990s, had deprived unions of their social power as union membership dropped significantly, partly because of the consequences of automation but mainly because of class warfare policies from above. Today, in the United States, only 12 percent of all workers are unionized, down from over 24 percent in 1979; in the UK, slightly more than a quarter of all workers are union members.

The decline in union membership has been a major factor contributing to the rising trends in inequality, as income shifted from labor to capital. As the conservative British publication The Economist revealed recently, “the ‘labour share’ of national income has been falling across much of the world since the 1980s,[40] while the profit share for capitalists in places like the United States (and obviously everywhere else) has been rising.” [41]

Structural reforms stand “as a euphemism for deregulation, reduction of union rights, etc.”

The decline of organized labor and the rise of income and wealth inequalities in the advanced industrialized economies signify not merely an economic, but also a political shift in the balance of power between labor and capital. In terms of political power, what these developments mean is that labor’s influence over the state has also shrunk significantly, which in turn helps to explain the obsession of contemporary governments with neoliberal structural reforms and their nonchalant attitude toward the concerns of working populations.

In Europe, neoliberal structural reforms have been adopted as a major objective of economic policy since the Maastricht Treaty, primarily as a means of increasing competitiveness – and therefore securing a larger share of profits for capital. In general, structural reforms stand “as a euphemism for deregulation, reduction of union rights, etc.” [42] With the European Central Bank having jumped on the bandwagon, structural reforms are mandated by EU authorities alongside austerity for the purpose of fiscal consolidation. The claim, of course, is that “structural reforms” will produce greater growth potential and thus more jobs.

As with austerity, the claims about the alleged benefits of neoliberal structural reforms were not drawn on the basis of measurable data but rested purely on ideological bias.

In other words, the answer to the very problems created by antigrowth austerity policies now rests with radical labor market reforms, further liberalization, and more privatization. To be sure, in the case of all four peripheral eurozone countries discussed above, the same claims were made by the EU authorities and IMF officials – namely, that there were labor market inefficiencies that contributed to a loss in competitiveness (and thus to high deficits and debt levels as well as high unemployment rates) and that reducing the cost of labor would increase employment. In all four cases (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain), the alleged culprit was the public sector (allegedly bloated, corrupt, and with an inherent propensity to run huge deficits), while inflexible markets and high labor costs were the forces that supposedly prevented rapid recovery. There was total silence over the fact that it was actually the private sector (mainly the banking and financial sector) that brought about the calamity in all four countries in question, even if in the case of Greece the crisis took the shape of a fiscal crisis when private lenders (mostly European banks overflowing with cash that could not find proper investment opportunities) stopped pouring excessive amounts of money into the economy.

As with austerity, the claims about the alleged benefits of neoliberal structural reforms were not drawn on the basis of measurable data but rested purely on ideological bias, which reflected particular class positions. The idea that anyone can measure or say with certainty by what amount, if any, flexible labor markets add to GDP is simply absurd. What we do know, however, is that structural reforms tend to exacerbate income inequality and lead to precarious employment. Moreover, if high labor costs are a drag on an economy, why have the bailed-out eurozone countries – whose working populations have experienced huge cuts in wages and salaries in the course of the ongoing crisis – not yet witnessed growth and a sharp increase in employment rates?

The problem with structural reforms is that they treat labor markets like any other market. In this context, workers are commodities to be used and disposed of like any other product. Hence the retreat of contemporary policymakers and mainstream economists from the “full employment” vision that was central to Keynes’s own work. Hence, also, the double standard applied in today’s labor markets to corporate executives and workers, with the former enjoying all sorts of privileges, outrageous salaries, and highly generous protection packages in the event of termination while average workers enjoy minimum wages, no protection from dismissal and lower unemployment benefits.

What “structural reforms” do accomplish, however, is create highly flexible labor markets where precarious work becomes the most prevalent feature, increased inequality . . . and . . . privatization.

In the bailed-out countries of the eurozone, in addition to massive unemployment, structural reforms have brought about a new element in capitalist practices: Companies rarely pay their workers on time, in many cases delaying wage payments anywhere from three months to a year, and with payments made mostly in small installments. According to the Labor Institute of the General Confederation of Greek Workers, this practice applies today to more than half of all Greek businesses, with workers basically unable to do anything about it other than simply quit their jobs and join the ever-growing ranks of the unemployed – but without access to unemployment benefits. A similar (but not as widespread) phenomenon of delayed payments is also found to exist in Portugal, but, unlike in Greece, special arrangements are in place to provide some kind of protection to employees who suffer from the practice.

In sum, the evidence that “structural reforms” can boost jobs in the context of fiscal consolidation is hard, if not impossible, to locate in the case of the bailed-out countries of the eurozone. What “structural reforms” do accomplish, however, is create highly flexible labor markets where precarious work becomes the most prevalent feature, increased inequality the order of the day, and the transfer of public wealth into private hands through the policies of privatization a widespread practice. Even in the case of Ireland, which was already a poster child for neoliberalism for nearly two decades until the collapse of its banking sector in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008, the EU/IMF bailout program demanded a number of deep structural reforms in the labor market, in public health spending, in state assets, and even in water services. [43]

The notion that “structural reforms” can serve as a tool to solve major economic problems can best be described as a scam. Indeed, it appears to be the case, as Paul Krugman so pointedly put it recently, that “structural reform is the last refuge of scoundrels.” [44]

Are Exports a Troubled Economy’s Salvation?

Exports have been identified by the EU as a primary engine of growth, in all likelihood due to the success of the German experience with export-led growth, but also, one could argue, because of the overall neo-Hooverian posture [45] that its policymakers have adopted in the age of the crisis of the euro, in which the use of fiscal tools for the creation of jobs and growth has been permanently excised from the policymaking process. The suppression of wages in the eurozone periphery was intended to increase competitiveness and thus provide a boost to their exports. To some extent, this strategy has worked, in the sense that the trade balances of peripheral nations have been improved in the last few years, with Portugal, surprisingly enough, experiencing a most impressive increase in its exports, [46] but far more so Spain, which has not traditionally been a strong exporter. [47] In the case of Spain, in fact, “the share of exports in GDP . . . is converging toward Germany (52 percent in 2012) faster than in France and Italy.” [48] However, in the case of both Portugal and Spain, the rate of the increase in exports has proceeded alongside a similar fall in the rate of domestic consumption.

Exports are important, but they cannot provide a realistic way out of a recession, and they certainly cannot provide the number of jobs needed for the millions of unemployed in Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain.

Ireland’s exports have also gone up, keeping the economy from a complete collapse and compensating for falling domestic demand. But in the case of Ireland, where exports have been increasing annually since 2010 by an average of more than 5 percent over the previous year (DJEI 2013), this does not come as a surprise, because Ireland is home to many major export-oriented multinationals. However, it should be stressed that most jobs in Ireland are not to be found in the export-oriented industries but rather in the nonexporting sectors such as the hotel and hospitality industry, wholesale and retail, and transport and storage. [49] In fact, the link between exports and job creation is extremely weak in Ireland, making a mockery of the presentation of Ireland’s alleged recovery as a “success story,” [50] likewise in the case of Portugal and Spain, where the overwhelming majority of companies employ just a handful of workers. Moreover, in these countries the increase in exports seems to be directly related to the high unemployment rates that have reduced wages and labor costs.

In the case of Greece, the export trend has been rather disappointing. While there has been a surge of Greek exports in the last few years, it was driven by “mineral fuels, lubricants and related material.” [51] Thus, the increase in exports has been in the highly volatile oil-related products, while non-oil exports are struggling and have yet to return to their pre-crisis levels. Moreover, Greek exports are being increasingly directed toward non-EU nations – which clearly indicates that the competitiveness strategy applied in the case of Greece through the suppression of real wages is not having an effect on exports. [52]

Exports are important, but they cannot provide a realistic way out of a recession, and they certainly cannot provide the number of jobs needed for the millions of unemployed in Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain. In addition, it is not clear whether the increase in exports in Portugal and Spain reflects a structural or a cyclical change. With the eurozone expected to grow by merely 1 percent in 2014, foreign demand for Greek, Portuguese and Spanish products may not be sustainable for much longer. Furthermore, there is something dubious about the notion that all eurozone economies should be restructured in ways that allow them to run current account surpluses. The problem with this kind of thinking is that for all eurozone member-states to run current account surpluses, its major non-European trading partners (China? Russia? India?) must run deficits – or demand must come from outer space. Research has also shown that, historically, most nations tend to run deficits rather than surpluses, and that large current account surpluses are not sustainable in the long run. [53] On the basis of all of the above, it seems that the export-led growth envisioned by the current EU chiefs is just another dead economic dogma, representing yet another attempt to delay the demise of the eurozone – a demise that, if it comes to pass, will be driven by the eurozone’s flawed architectural foundations and its profoundly wrongheaded, indeed illegitimate, economic policies.

Conclusion

The EU/IMF rescue programs that Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain entered into were designed, above all, to provide a “firewall” for the protection of the European banking system and thus the single currency itself, rather than solve the economic problems facing those nations. The rescue programs demanded great sacrifices on the part of average citizens in those countries due to the reckless practices of banks and the financial sector – while the banks themselves came out clean and the eurozone returned to being a playground for bond investors. In this context, the EU/IMF duo pressed hard for austerity and structural reforms for the bailed-out countries purely on the basis of an ideological conviction (for there was no empirical evidence to back these claims) that such measures would enhance confidence, which in turn would create the proper conditions for a return to growth and higher employment.

Looking at the current situation in the four bailed-out countries of the periphery (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain), there is not a single trace of solid evidence that the austerity / structural reforms / export-led growth approach insisted upon by the EU and the IMF has paid any solid economic and social dividends. While the government deficits have certainly been reduced by substantial margins and the trade balances have improved, government debt has increased dramatically, and unsustainably, for all four countries, the unemployment rates have climbed to catastrophic levels, the provision of public services has all but collapsed – including in the sensitive area of public health care – and poverty and inequality have widened by considerable margins. While exports have picked up due to the sharp drop in wages (though not in the case of Greece), aided both by the structural reform policies dictated by the EU/IMF duo and the increased rates of unemployment, domestic consumption has fallen significantly and people with high levels of education and technical and professional skills are leaving their homelands en masse in pursuit of a better future abroad. The job situation in Ireland is so pressing – even though the unemployment rate has recently dropped to 12 percent, primarily because of the huge numbers of people without jobs who have been leaving the country since the start of the crisis – that the government is encouraging the unemployed to emigrate and seek employment in other European nations. Still, Chancellor Merkel and the entire chorus of neoliberals in Ireland and elsewhere dare to call the Irish bailout program a “success story.”

In this context, the crisis in the eurozone periphery not only continues, but it could also intensify in the near future, especially once the citizenry in those countries realizes that the game is rigged in favor of finance capital and big business. For this is exactly what the current EU policies are designed to do, to the detriment of a decent standard of living for the average citizen.

The original version of this article was published as Public Policy Brief No. 133 (2014) by the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

NOTES:

1.This article does not deal with Cyprus, which was “bailed out” only recently.

2. Bruno Waterfield, “EU Put Eurozone Safety before Greece during Bailout, IMF Report Claims.” The Telegraph, June 5, 2013.

3. Mark Blyth, Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

4. Peter Spiegel and Kerin Hope, “EU’s Olli Rehn Lashes Out at IMF Criticism of Greek Bailout.” Financial Times, June 7, 2013.

5. Avgi, “Παραδοχή Όλι Ρεν: ‘Θυσιάσαμε την Ελλάδα χάριν της Ε.Ε. και των τραπεζών.'” January 15, 2014.

6. IrishCentral, “Ireland Has EU’s Highest Rate of Emigration with One Person Leaving Every Six Minutes.” November 21, 2013.

7. Maria Tadeo, “Unemployed Told to Leave Ireland in Desperate Move to Slash Welfare Costs.” The Independent, December 13, 2013.

8. BBC News Europe, “German Chancellor Angela Merkel Praises Ireland’s Bailout Exit.” March 7, 2014.

9. C. J. Polychroniou, “The Myth of the Greek Economic ‘Success Story.’ ” C. March 2014.

10. The emphasis is on vocational education and training systems, with the help of a budget line that amounts to 6 billion euros in total, ignoring the fact that there are already millions of young people throughout Europe with higher education degrees and professional skills who cannot find jobs simply because the eurozone, in particular, has a general macroeconomic problem where there is no job growth. For details of the EU initiatives to address the problem of youth unemployment, see European Commission, “EU Measures to Tackle Youth Unemployment.” Factsheet 2013.

11. Whether the EU is taking its cue on economic growth from Germany’s economic model, which is based on exports, or because Germany dominates the eurozone’s policymaking environment hardly matters at this stage, as any alternative policy option for the eurozone would necessarily imply some kind of direct confrontation with Europe’s current hegemonic power – which is none other than Germany itself.

12. See L. Randall Wray, “Minsky’s Approach to Employment Policy and Poverty: Employer of Last Resort and the War on Poverty.” Working Paper No. 515. Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. September 2007.

13. Helge Berger and Martin Schindler. “A Long Shadow over Growth.” Finance & Development 51, no 1, March 2014.

14. Italy has so far avoided a bailout, but its economy is in a mess, having contracted for the past two years, with the current official unemployment rate standing at 12.9 percent.

15. See Ernst & Young, “Eurozone Forecast.” March 2013.

16. See Richard J. Gordon, “The Demise of US Economic Growth: Restatement, Rebuttal, and Reflections.” Working Paper No. 19895. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. February 2014; and Richard J. Gordon, “Is US Economic Growth Over? Faltering Innovation Confronts the Six Headwinds.” Working Paper No. 18315. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. August 2012.

17. Cited in J. B. Agassi, “The Rise of the Ideas of the Welfare State.” Philosophy of the Social Sciences 21, no. 4, December 1991, p. 452.

18. Cited in Robert LaJeunesse, Work Time Regulation as Sustainable Full Employment Strategy: The Social Effort Bargain. New York: Routledge, 2009.

19. See Jamie Peck, Workfare States. New York: Guilford Press, 2001.

20. Alternatively, the definition of full employment offered by the late William Vickrey in 1993: “I define genuine full employment as a situation where there are at least as many job openings as there are persons seeking employment, probably calling for a rate of unemployment, as currently measured, of between 1 and 2 percent.” Cited in William Mitchell and Joan Muysken, Full Employment Abandoned: Shifting Sands and Policy Failures. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2008, p, 38.

21. It is true that economists have been divided over the question of capitalism and unemployment since the origins of modern political economy. Thus, in the 19th century, most liberal economists claimed that, if left on its own, capitalism would move toward a state of full employment, while Marx, on the other hand, not only brilliantly identified various kinds of unemployment, but also claimed that unemployment was necessary to capitalism. In the early 20th century, Keynes also accepted the view that capitalist economic operations could lead to high unemployment, but he maintained that a state of full employment is possible via government action. Hence, Marx and Keynes agreed in their critique of early classical economists, but proposed different solutions: Marx opted for the overthrow of capitalism and its replacement by a social order in which the direct producers owned the means of production, while Keynes proposed active government involvement for the management of capitalist crises by arguing that demand, not supply, was the key economic variable. Keynes worked all his life to dispel the myth of Adam Smith’s invisible hand, and his solution to the problem of capitalist unemployment was direct, voluntary employment – “to take the contract to the worker and distressed areas and regions” (cited in Pavlina R. Tcherneva , “Full Employment: The Road Not Taken.” Working Paper No. 789. Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. March, 2014.

22. Michal Kalecki,”Political Aspects of Full Employment.” Originally published in Political Quarterly, 1943.

23. See Thomas. I. Palley, “Europe’s Crisis without End: The Consequences of Neoliberalism Run Amok.” Working Paper No. 111. Dusseldorf: Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) – Hans-Böckler-Stiftung. March 2013.

24. See C. J. Polychroniou, “A Failure by Any Other Name; The International Bailouts of Greece.” Policy Note 2013/6. Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. June 2013.

25. In my assessment of the goals and aims of the so-called “rescue” plans by the EU and the IMF, I do not mean to suggest or imply that policymakers are either ignorant of the consequences of the policies they prescribe or that they are not aware of alternative policy frameworks with the potential to deliver more socially desirable outcomes. On the contrary, I claim that they are fully aware of the economic and social repercussions that the policies they adopt will have for the majority of the people of a given nation, for they act in accordance with what is best for certain class interests and for the maintenance of the status quo.

26. See The Telegraph, “Jose Manuel Barroso Predicts Europe Will Escape Recession.” September 5, 2011.

27. See Philip R Lane, “The Irish Crisis.” Discussion Paper No. 356. Institute for International Integration Studies, Trinity College Dublin. February 2011.

28. See Stephen Burgen, “Spain’s Unemployment Rise Tempers Green Shoots of Recovery.” The Guardian, January 23, 2014.

29. See David Stuckler and Sanjay Basu, The Body Economic: Why Austerity Kills. New York: Basic Books 2013.

30. See Alexander Kentikelenis, Marina Karanikolos, Aaron Reeves, Martin McKee and David Stuckler, “Greece’s Health Crisis: From Austerity to Denialism.” The Lancet 383, no. 9918, February 22–28, 2014; and Anthony Faiola, “Greece’s Prescription for a Health-care Crisis.” The Washington Post, February 21, 2014.

31. See Charlie Cooper, “Tough Austerity Measures in Greece Leave Nearly a Million People with No Access to Healthcare, Leading to Soaring Infant Mortality, HIV Infection and Suicide.” The Independent, February 21, 2014.

32. See John Quiggin, Zombie Economics: How Dead Ideas Still Walk Among Us. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2012.

33. See Juno McEnroe, “Austerity Is Not Working, Charity Report Suggests.” Irish Examiner, February 15, 2013.

34. See SAPRIN (Structural Adjustment Participatory Review International Network), “The Policy Roots of Economic Crisis and Poverty: A Multi-country Participatory Assessment of Structural Adjustment.” First edition. April 2002.

35. See Alan W. Cafruny and Magnus Ryner, eds. A Ruined Fortress? Neoliberal Hegemony and Transformation in Europe. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers 2003; and C. J. Polychroniou, “The New Rome: The EU and the Pillage of the Indebted Countries.” Policy Note 2013/5. Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. May 2013.

36. The same could be said of the Levy Economics Institute’s latest strategic analysis of the Greek economy; see Dimitri B. Papadimitriou, Michalis Nikiforos and Gennaro Zezza, Prospects and Policies for the Greek Economy. Strategic Analysis. Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. February 2014.

37. See C. J. Polychroniou, “The Political Economy of Predatory Capitalism.” Truthout, January 12, 2014.

38. See James O’Connor, The Fiscal Crisis of the State. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1973.

39. This is the argument made by Daniel Stedman Jones in his book Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

40. The Economist, “Labour Pains.” November 2, 2013.

41. See Tali Kristal, T. 2013. “The Capitalist Machine: Computerization, Workers’ Power, and the Decline in Labor’s Share within US Industries.” American Sociological Review 78, no. 3, June 2013, pp. 361-389.

42. See Philip Arestis and Malcolm Sawyer, “‘Structural Reforms’ and Unemployment.” Triple Crisis, January 16, 2014.

43. See Darragh O’Neill, “Remaining Structural Reforms Under the EU/IMF Programme.” Public Policy, September 18, 2013.

44. See Paul Krugman, “Structural Reform Is the Last Refuge of Scoundrels.” The New York Times, February 21, 2014

45. See C. J. Polychroniou, “Neo-Hooverian Policies Threaten to Turn Europe into an Economic Wasteland.” Policy Note 2012/1. Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. March 2012.

46. See Peter Wise, “Portugal the Surprise Hero of Eurozone Growth as Exports and Tourism Prosper.” Financial Times, February 16, 2014.

47. See Angeline Benoit and Manuel Baigorri, “Spain’s Crisis Fades as Exports Transform Country.” Bloomberg, June 4, 2013

48. See William Chislett, “Spain’s Exports: The Economy’s Salvation.” Analyses of the Elcano Royal Institute. December 4, 2013

49. See Martina Lawless, Fergal McCahn and Tara McIndoe-Calder, “SMEs in Ireland: Stylised Facts from the Real Economy and Credit Market.” February 29. Draft paper presented at the Central Bank of Ireland conference, “The Irish SME Lending Market: Descriptions, Analysis, Prescriptions,” Dublin, March 2, 2012.

50. See Fintan O’Toole, F. “Ireland’s Rebound Is European Blarney.” Op-Ed. The New York Times, January 10, 2014

51. See Ronald Janssen, “European Wage Austerians Are Getting Desperate! What Really Happened with Greek Exports.” Social Europe Journal, October 18, 2012

52. Dimitri B. Papadimitriou, Michalis Nikiforos, and Gennaro Zezza, “Prospects and Policies for the Greek Economy.” Strategic Analysis. Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. February 2014: 4-5.

53. See Sebastian Edwards, “On Current Account Surpluses and the Correction of Global Balances.” Working Paper No. 12904. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. February 2007.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $47,000 in the next 8 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.