For the nose, Skid Row in Downtown Los Angeles on a Saturday night is a shit-wreaking party. For the eyes it is a glimpse at the floor below America’s social ladder. For the soul it is the recognition of a nightmare that plagues everybody in a capitalist society: what it would mean to fall off that ladder.

I went the night after the Fourth of July. The leftover fireworks exploding intermittently within the darkened, fifty-foot square blocks of seafood warehouses and faded motels sound like urban warfare. Hundreds of men and women without homes cloister on the sidewalks, murmuring to each other or themselves behind the fabric of tents and tarps, some asleep on cardboard, a few slumped on the bare sidewalk, and still more swapping bottles of booze or dope or needles. It’s common to see elderly people in a babbling daze, gnashing their jaws silently to themselves. But the people that you watch most, carefully and discretely, are the screaming, half-clothed men who flail their arms and charge through the streets at phantoms that aren’t there.

Above the sidewalks, businesses and even some shelters have installed sprinkler systems to wash away the perceived human filth resting below every morning. Some of the buildings feature the same sun-worn sign, prominently:

(Photo: Aaron Cantu)

(Photo: Aaron Cantu)

Yet despite the posted warnings and morning rinses, many acknowledge that Skid Row’s population of street people is growing, a byproduct of the rising number of homeless people in Los Angeles County, which shot from 50,214 in 2011 to 57,737 last year—a bigger jump per capita in that period frame than all other cities in the nation, according to a definitive survey. The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority indicates that the rise is made up almost entirely of single adults, three quarters of whom had no secure place to sleep on a given night last year. About 55 percent of these people suffer from three or more disabilities—”indicating [they] face multiple barriers to overcoming their homelessness,” according to the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce.

With those numbers expected to rise, there is a desperate need on the part of activists and some officials to locate supportive housing as quickly as possible. However, they’re running into impediments put in place by a coalition of local developers, overseas investors, and city officials that grind even the most obvious solutions to homelessness down to illusory pipe-dreams.

No campaign is more emblematic of this fact than the battle between activists and developers for the Cecil Hotel.

(Photo: Aaron Cantu)

(Photo: Aaron Cantu)

The Cecil Hotel is a not a luxury resort. To the contrary: It’s long been known as a cheap stay for those passing through town, and at various points in its history, it has hosted serial killers who murdered within its walls. More recently, the corpse of a young woman was found decomposing in the hotel’s water tank, where it leaked soupy flesh into occupants’ sinks and showers for two weeks (the woman, who suffered from bipolar disorder, was believed to have fallen in by accident).

But whatever its sordid history, the hotel, which is located at the edges of Skid Row, is a complex of living spaces in a neighborhood where thousands have nowhere to live. So its conversion into a residence for formerly roofless seems like a no-brainer, especially because it was designated for affordable housing by the city: The Cecil was one of 18,777 units protected by a set of laws passed by the City Council in 2008 to forbid developers from flipping low-income houses.

“When certain neighborhoods have homes on steroids and others no longer have a place for the poor to sleep, the social fabric is torn,” said City Council President Eric Garcetti (who is now the mayor) to the LATimes at the time the rules was passed.

The plan to turn the Cecil into a space for permanent housing was backed by homeless advocates, grassroots activists, and even the owner of the building. In the end, however, that plan was rejected by the city, and today 550 of its 600 rooms remain vacant.

The Cecil proposal was put forward by the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services and “Home for Good,” an initiative by United Way of Greater Los Angeles and the L.A. Chamber of Commerce. Similar plans nearly always result in failure, doomed from the beginning by terminal inertia, bureaucracy, and scarce funds. But the Cecil was the real deal: with $10 million from the city, it would have transformed 384 of the rooms into efficiencies complemented by on-site mental heath services. 150 other rooms would have been rented at market or reduced rates.

384 is a drop in the bucket of the estimated 5,000 who sleep on Skid Row’s asphalt, but it would have been a model of possibility. Ultimately, though, Los Angeles County Supervisor Gloria Molina sided with developers and rejected the Cecil plan. Their purported humanitarian rationale: That there is already an over-concentration of homeless services in downtown, and the Cecil would have been a burden for the area’s revitalization.

“The addition of these units and services…comes to a neighborhood that is already highly concentrated with Supportive and Affordable housing projects,” writes Tom Gilmore, who owns several boutique restaurants and hotels in the area, in an email. This is true: There is a denser concentration of shelters and missions in Skid Row and the surrounding areas than anywhere else in the country.

The developer notes there are already three other buildings—the Rosslyn, New Genesis Apartments, and New Pershing Apartments—designated to serve a mixed-income clientele (with 439 mixed units in total), and that having the Cecil in place would be “like having an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting in a bar,” because of the notoriously easy access to drugs and alcohol in the neighborhood.

The Cecil Hotel, located at 640 Main Street in Downtown Los Angeles. (Photo: Splash News)

The Cecil Hotel, located at 640 Main Street in Downtown Los Angeles. (Photo: Splash News)

Ironically, one of mixed-income buildings cited by Gilmore is like having an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting in a bar, or in this case, a gastropub. Great Balls, a new restaurant located on the ground floor of New Genesis Apartments, got approval from the city this year to sell beer and wine after a city zoning administrator initially turned it down. New Genesis houses a few dozen formerly homeless persons, all with severe substance abuse issues, and the building maintains recovery services and a full-time staff to help residents stay sober.

In light of the Great Balls-New Genesis contradiction, it is difficult to believe Gilmore’s objection to the Cecil is limited to concern for tenants’ welfare. More revealing is what he says further along in his email: “Additional units…will present a serious impediment to the growth of an emerging neighborhood.” That concern may form the bulk of his rejection, since Gilmore has more than money invested in the neighborhood: The Old Bank District, where the Cecil and his properties are located, is his brand. He has guided the area’s development for over a decade since securing nearly $27 million in loans from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development to convert old, pre-war bank buildings into lofts.

Ultimately however, the decision to terminate the Cecil deal came from Los Angeles County Supervisor Gloria Molina, who echoed Gilmore’s concern about a saturation of homeless services downtown. In the past, Molina has pushed for homeless services outreach across the county, but like Gilmore, she also champions the type of “revitalization” that activists charge discriminates against the homeless. For example, she was a driving force behind the new Grand Park in the middle of downtown, where there are a number of things in place—like a ban on sitting on the grass—to discourage vagrants from getting too comfortable.

The rejection of the Cecil came after the project was assumed to pass, and few think the plan is likely to be revisited. Nevertheless, activists with the Los Angeles Community Action Network, or LACAN, which organizes renters and homeless residents of Skid Row, are not letting the plan die quietly. Months after it was tossed out, LACAN continues to meet with officials and rally in the streets, hoping that through will and show of force, they can get the Cecil back on the table.

General Dogon of LACAN demands the Cecil Hotel. (Video: Aaron Cantu / Vimeo)

The new headquarters of LACAN is located near 6th street and Stanford Ave, in the heart of Skid Row. On one wall is a giant dry erase board with a drawn-up calendar of events, but save for a some activist regalia—a poster of Malcolm X, a sign that reads HOUSE KEYS NOT HANDCUFFS—the room is mostly sparse, with many belongings still packed away in boxes after a recent move. Like the residents of Skid Row, LACAN is somewhat transient, vulnerable to grumbling building owners and rising rents.

Its members, however, are consistent in their resolve. Many are or were once homeless themselves, and they believe LACAN differs from other missions in the area because of its emphasis on community development. This is more valuable than simply providing meals and temporary beds, they say.

“LACAN is different because we believe in leadership development, and because we hire people off the street” says Adam Rice, who first came into contact with LACAN while he was living on the streets of Skid Row himself. “LACAN gave me skills and support, and as it went along and they built that support, they taught me more skills I could use to move forward.” Rice was eventually hired by LACAN to head its anti-eviction campaign.

The group is known as much for its relentlessness as its victories. Despite an annual budget that is a little under $1,000,000, it has forced major changes from the city for the benefit of Skid Row’s street dwellers, beginning with a successful harassment suit filed in 1999 on behalf of homeless residents against the Central City East Association, the business improvement lobby that once dispatched armed private security personnel into the area. The security officers were eventually forced to drop their 9 millimeter pistols and undergo sensitivity training.

Recently there have been other victories. LACAN sued the LAPD in 2008, along with the ACLU of Souther California, for harassment against homeless residents settling for millions of dollars. Right before funding for Skid Row’s only two parks was to run dry early last year, LACAN members worked with City Councilmember José Huizar to whip up $50,000 in renewed financing for the parks. And in one of its biggest victories yet, LACAN partnered with a broader coalition to secure a settlement of $15 million for a trust fund for low-income housing, paid for by the Anschutz Entertainment Group, who the plaintiff sued over its proposed construction of a new NFL stadium in Downtown Los Angeles (cost: $1.2 billion).

LACAN is currently suing both the LAPD and the CCEA for infringing on its right to protest. But its most Sisyphean mission is opening the Cecil Hotel’s rooms to Skid Row’s homeless.

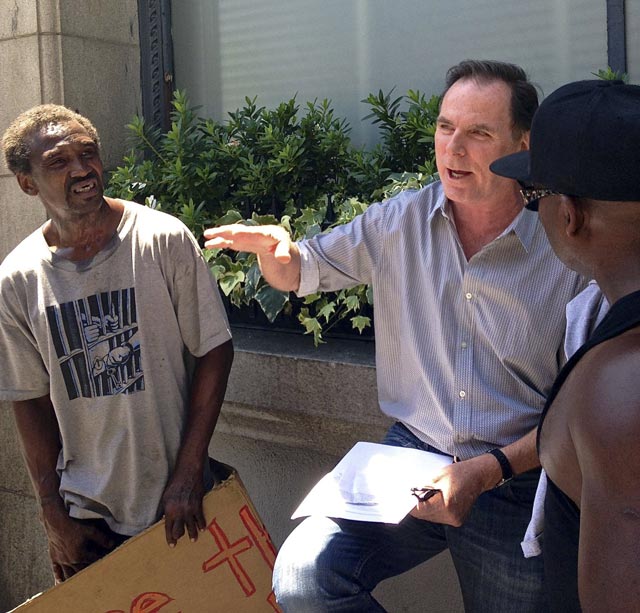

Members of LACAN meet with Tom Gilmore. (Photo: Aaron Cantu)

Members of LACAN meet with Tom Gilmore. (Photo: Aaron Cantu)

In the last few months, the organization has confronted Tom Gilmore, who is also a former commissioner of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, as well as the Central City Association (CCA) of Los Angeles, a powerful lobby that represents the city’s business interests. Throughout the summer, LACAN has held a series of direct actions demanding renewed negotiations on the Cecil.

At a demonstration in front of a CCA meeting on July 28, LACAN members banged drums, chanted and paraded through the streets. “The business people here meet with all the politicians in the city,” said General Dogon, a leading organizer with the group. “That’s who they working for.” As we spoke, a man driving a black BMW on the way to the CCA meeting lifted his middle finger to protesters. “Yeah, backatcha” said Dogon, returning the gesture.

Members of LACAN rally at a meeting of the Central City Association. (Photo: Aaron Cantu)

Members of LACAN rally at a meeting of the Central City Association. (Photo: Aaron Cantu)

A few days later, on August 1, LACAN is on Main Street in full force to demand that the Cecil plan be renewed, despite all signs that it will not. Protesters symbolically push red shopping carts through the streets—the same carts issued to Skid Row folk by the Los Angeles Catholic Worker shelter for mobile storage of belongings—and sing and dance.

The militant showing simmers the tempers of some LACAN members, including Zandra Soils, a formerly homeless woman who attempts to pass out flyers detailing their cause to the patrons of an upscale restaurant on the block. She bristles when they ignore her.

“They down in our territory but they don’t want no flyers,” she said. “I hate the way they see us like we’re trash. They just stuck on top of the world and don’t like what they see.”

Finally, the man who protesters demand to see—Tom Gilmore—appears. It is not the first time the two forces have met. Gilmore’s meeting with LACAN this morning is like watching a cosmic duality orbit itself, each pole forever spinning around the other without ever touching beyond interpersonal formalities.

Members of LACAN confront downtown developer Tom Gilmore. (Video: Aaron Cantu / Vimeo)

This wasn’t the last time LACAN hit the streets for the Cecil, and anything else standing between Los Angeles’s homeless and permanent affordable housing. But they are grappling with forces bigger than Tom Gilmore, the CCA and even the officials whom they petition.

Downtown Los Angeles is being transformed by macroeconomic policies forged in the global response to the financial crisis, forces that are now spurning a competition between the Western world’s most posh cities—including Los Angeles—for outside investment in luxury property markets.

These economic drivers and their facilitators on the ground will be the focus of the next installment of the Street Sweeper series.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $24,000 by the end of today. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.