What do private prisons have to do with the upcoming elections?

Let’s start with several hundred thousand dollars in campaign contributions.

Idaho, for instance, has recently seen how campaign contributions can ease corporate accountability when scandals and lawsuits hit. Corrections Corporation of America, the country’s largest private prison provider, had been contracted to run the Idaho Correctional Center, the state’s largest prison, when it opened in 2000. CCA has also contributed $20,000 to Idaho Governor Bruce Otter’s campaign since 2003.

Over the years, story after story of the violence inside the Idaho Correctional Center emerged. The prison, which was dubbed “Gladiator School,” has been the subject of multiple lawsuits around the widespread brutality and violence, much of which was deliberately allowed by prison staff as a management tool. In 2010, the ACLU filed a federal class action lawsuit on behalf of prisoners against prison officials and the CCA. The suit highlighted 24 cases of assaults that occurred between 2006 and 2010. The following year, CCA settled with the ACLU, agreeing to changes around staffing and safety. However, violence and lawsuits continued. In addition, it seemed that CCA also billed the state for more than 4,000 staff hours that were never worked.

In January 2014, the state opted not to renew its contract. Although Governor Otter recently stated that he recused himself from the settlement negotiations, top members of his staff did not, agreeing on terms that heavily favored CCA. CCA, which received $29 million per year under the contract, settled with the state for only $1 million for the unworked staff hours. The settlement states that all staffing disputes are “fully, forever, irrevocably and unconditionally” settled. In March, the FBI began an investigation, but the terms of the settlement prevent the state from pursuing civil penalties against the corporation.

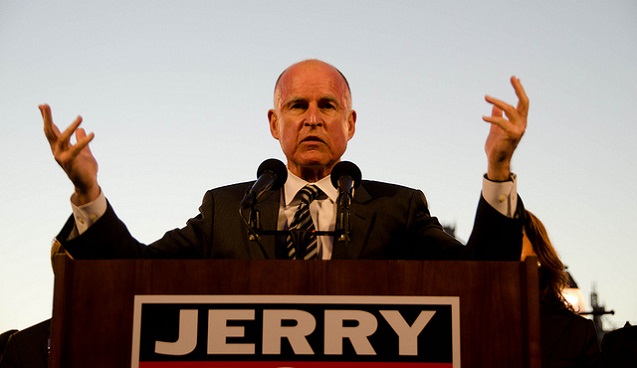

Otter is not the only politician whose campaign coffers benefited from private prison industries. In 2010, GEO Group, the country’s second largest private prison company, contributed $25,900 to Jerry Brown’s successful run for California governor. In 2013 California awarded GEO contracts to reactivate two 700-bed prisons. The state also awarded GEO a contract for a third prison, which included an expansion from 600 to 700 beds. According to its 2013 annual report, 66 percent of GEO’s revenue came from contracts to operate 59 prisons and immigrant detention centers (approximately 65,000 beds).

In 2014, Brown received $54,000 from GEO for his reelection campaign. As reported earlier in Truthout, in April 2014, California contracted with GEO Group to open a 260-bed women’s prison. The contract allows GEO to double the number of beds, potentially increasing its four-year revenue from $38,132,640 to $66,394,276.

Money isn’t the only way that private prison companies bolster campaigns. In Florida, GEO Group contributed $3,000 directly to Florida governor Rick Scott’s re-election campaign. But that wasn’t its sole campaign contribution. Founder and current GEO CEO George Zoley hosted a $10,000-a-plate fundraising dinner in July 2014. GEO Group previously contributed $25,000 to Scott’s 2010 inauguration, while Zoley himself donated several thousand dollars for Scott to help upgrade the governor’s mansion. (Jamie Trinkle, the coordinator of Enlace’s Private Prison Divestment campaign, noted that Scott’s rival in this race, former governor Charles J. Crist, has received $80,700 from GEO Group in the past.)

It’s not just gubernatorial candidates who are the beneficiaries of CCA and GEO Group’s money. Peter Cervantes-Gautschi is the executive director of Enlace, a racial and economic justice organization that runs a campaign to divest from private prison industries.

In a phone interview with Truthout, he noted that both GEO and CCA have contributed to the campaigns of other lawmakers up for reelection. Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell has received $30,400 from CCA since 2006, and his campaign won $40,000 from GEO Group in 2013. Similarly, Senate Minority Whip John Cornyn has received $5,200 from GEO Group this year and $13,000 from CCA since 2006.

“No matter what happens [on November 4], the private prison industry will be well wired to get more contracts,” Cervantes-Gautschi predicted. In 2012, contracts with federal agencies, such as ICE, the Bureau of Prisons and the US Marshall Service, accounted for $752 million, or roughly 44 percent of CCA’s revenue.

Louisiana US Senator Mary Landrieu, for instance, received $15,000 from GEO Group in 2014 alone. Landrieu is a member of the Senate Appropriations committee, which allocates funding to numerous federal agencies, including the Department of Homeland Security and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Both CCA and GEO Group hold numerous contracts to operate ICE detention facilities. In 2007, Congress mandated that 34,000 beds in immigrant detention be filled every day. ICE pays $2 billion each year to meet this quota.

What do these contributions have to do with the upcoming elections? And why should voters be concerned?

“In 2013, CCA spent $7 to $800,000 in campaign contributions. A company like CCA has a fiduciary responsibility to its shareholders to get results for their money,” says Alex Friedmann, managing editor of Prison Legal News. But, he notes, “CCA is a company that gets 99.9 percent of its income from the government. It would be very naïve to say that the company gets nothing in return.” According to its annual report, in 2013, 44 percent of CCA’s revenue (approximately $740 million, a slight decrease form $752.2 million in 2012) came from federal contracts.

But, Friedmann adds, “When private prison industries lobby and give contributions to politicians, this prevents government from examining alternatives like sentencing reform, investing in alternatives to incarceration, changing parole and criminal justice policies, and considering how to keep people out of prison in the first place.”

Should a Candidate’s Personal Investments Matter?

For more than 20 years, Illinois has had little reason to think about the private prison industry. In 1990, the state passed a moratorium on private prisons. But the moratorium did not include private federal facilities. In 2012, CCA attempted to build an immigrant prison in Crete just outside Chicago in 2012. The effort failed but, recalled Illinois representative Kelly Cassidy, “It was a huge battle and a controversial one.”

In 2013, GEO Group won a contract with the state’s Department of Corrections to monitor reentry contracts. When John Maki, the executive director of prison watchdog group the John Howard Association, learned about the contract, he contacted Governor Pat Quinn’s office to voice opposition. “This is a governmental responsibility,” he told Truthout. “People should not be getting rich off incarceration. Government should never delegate the deprivation of liberty to a private corporation.” The governor agreed with his stance and quickly scuttled the deal.

Though unsuccessful, these attempts showed that the moratorium was not set in stone – that private prison corporations may be able to begin business in the state. Illinois Representative Kelly Cassidy introduced HB5658 to extend the moratorium to privatizing parole and other forms of Department of Corrections supervision.

“Within minutes of the bill being assigned a number, there were two GEO lobbyists in my office with raised voices,” she told Truthout. “They were there every single day, trying to get me to drop the bill.” The committee hearing was contentious, she recalled, the first time she had seen it become so in the criminal justice arena. “Fundamentally, when you’re attacking someone’s pocketbook, they get angry,” she said. “But it’s distasteful when you’re talking about profiting off corrections.”

Quinn’s opponent in this year’s gubernatorial race is Bruce Rauner, who served as chairman of the private-equity firm GTCR for two decades. Rauner retired from GTCR in 2012 but remains an investor. After his retirement, GTCR bought a private company called Correctional Healthcare Companies (CHC), which contracts with prisons and jails to provide medical, dental and mental health care.

In 2012, CHC settled a lawsuit charging the company with “deliberate indifference” to the medical needs of a boy under its supervision. The suit charged that CHC waited more than 14 hours to send the boy to the hospital after he first complained about severe testicular pain. The suit charged that one of the boy’s testicles had to be surgically removed as a result of the delay. The terms of the settlement were not disclosed.

In 2013, Illinois awarded CHC a five-year contract to provide medical, dental and mental health treatment to the 900 youth, ages 13 to 20, in six state-run juvenile detention centers.

CHC was also the owner of Judicial Correctional Services, which operates private probation in 12 states.

“With private probation, the state doesn’t actually pay the companies,” explained Lauren-Brooke Eisen at the Brennan Center for Justice. Instead, the person on probation pays the fee to the company. People placed on private probation have often been arrested for offenses that don’t merit jail time, like speeding, driving without a license or insurance, shoplifting, public drunkenness, or noise complaints. They are also those least able to immediately pay their court fines or restitution, thus landing them under the supervision of companies like Judicial Correctional Services. Each month, their fees add up. Eventually those unable to pay face jail time. But private probation companies have little to no incentive to help probationers meet these fees and end their supervision.

“As private companies, their incentive is to make money, which means keeping people on their rolls,” Eisen pointed out. “Their incentive is not to rehabilitate or help people find treatment, educational services, employment or other needed services.”

Rauner has said that, if elected governor, he will put his money in a blind trust. But his campaign spokesperson Mike Schrimpf told the Better Government Association that Rauner also has no plans to divest from GTCR, meaning, as the Better Government Association has pointed out, he will be responsible for overseeing a contract in which he has a financial interest.

Should a Candidate’s Personal Investments be a Matter of Public Concern?

Jamie Trinkle, Enlace’s prison divestment campaign coordinator, says yes. “When state politicians are personally invested in private prisons or have significant holdings with a major private prison investor, they have a personal incentive to increase state spending on private prisons, promote mass incarceration within their state and permit federal contracts with private prisons within their state.”

Representative Cassidy agrees. “This is not the business we should be in, especially if we’re interested in safer communities and smaller prison populations. Corporations like this profit when people fail.” She also notes that Quinn has strongly supported the fight to stop CCA from building an immigrant prison in Crete in her bill to extend the private prison moratorium act.

“He put his muscle behind it,” she said. Would a candidate with a financial interest in private prisons have done the same? “There’s a stark difference between Quinn and Rauner. And it [Rauner’s investments] certainly doesn’t pass the sniff test,” she said.

“When elected officials have strong ties to private prison companies, you see sentencing laws become incredibly strict, the privatizing of services such as halfway houses and probation, and a market incentive to churn people through the system,” stated Sheila Bedi, Associate Clinical Law Professor at the Northwestern University Law School and an attorney with the Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center, a public interest law firm.

Bedi should know. In 2010, as deputy legal director of the Southern Poverty Law Center, she filed suit against GEO Group for the rampant physical and sexual assaults, as well as psychological abuse, including prolonged solitary confinement, at the Walnut Grove Youth Correctional Facility, which housed boys ages 13-22, in Mississippi. Charges included numerous instances of staff having sex with the boys.

In 2012, the courts agreed with the charges, writing that the GEO-run prison “has allowed a cesspool of unconstitutional and inhuman acts and conditions to germinate, the sum of which places the offenders at substantial ongoing risk.” That year, GEO discontinued operating not only Walnut Grove, but also two other prisons with which it had contracted with Mississippi.

“Illinois’s criminal justice system is already desperately broken because of an overreliance on mass incarceration,” she told Truthout. “When you mix that with a profit incentive, you’ll get a complete disaster.

Keepin in Mind that it’s Not just Private Prisons

While GEO Group contributed $54,000 to Jerry Brown this year, the California Correctional Peace Officers Association, which represents guards in state-run prisons, has contributed $107,400. CCPOA has opposed prison privatization, equating the issue with a loss of state jobs.

Craig Gilmore is amember of Californians United for a Responsible Budget, which opposes all prison expansion and advocates for decarceration. He pointed out that contributions are not the total end game.

“Not having taken $54,000 from GEO wouldn’t make Brown’s politics – not even his prison politics – any better,” he said. But, it’s worth paying attention to who takes money “as a lens to focus on what the issues are that are not on the front page of The New York Times or The L.A. Times or even covered in the electoral race. Paying attention to campaign money is a way to see how a particular policy is emerging, learn what policies are still being fought out and learn about ways to get involved in changing these policies.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.