Timothy Loehmann, the Cleveland police officer who shot 12-year-old Tamir Rice to death in November, was previously deemed “unfit” by a deputy chief to be a cop in late 2012 after having served only six months as a police officer with the Independence Police Department in Ohio before resigning under pressure. In March 2014, he landed a policing job in Cleveland — where he would then go on to shoot Rice within two seconds of arriving to investigate a complaint regarding the boy carrying what turned out to be a fake pellet gun.

Loehmann, according to internal records, was also found to have failed the Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s Department’s written cognitive entrance exam when he applied for a deputy sheriff position there in September of 2013. He also couldn’t make the cut at police departments in Akron, Euclid or Parma Heights, failing similar exams.

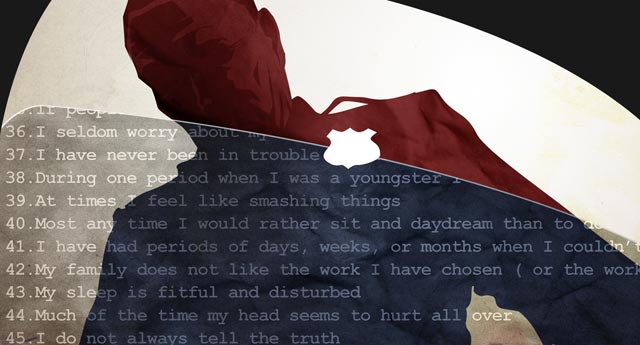

But despite his previous failures, there was one assessment Loehmann did pass during his brief tenure with the Independence Police Department: his psychological evaluation.

Loehmann’s psychological assessment, which also evaluated his personality type and behavior, determined him fit for the job prior to hire. Just a few months later, Independence Deputy Chief Jim Polak recommended Loehmann be cut loose, writing that Loehmann was “not mature enough in his accepting of responsibility or his understanding the severity of his loss of control” after he had multiple emotional breakdowns during training. Loehmann was allowed to resign.

Dr. Thurston Cosner, the licensed psychologist who administered Loehmann’s evaluation at Independence, noted that Loehmann “seems fairly rigid and perhaps has some dogmatic attitudes that could be problematic in police work” — while still recommending his hiring. Cosner also highlighted that Loehmann “appeared particularly stiff and naïve” during his evaluation, which had been expedited to meet a July 2012 hiring date, according to internal emails obtained by Cleveland Scene.

The Cleveland Police Department has acknowledged its mistake in failing to check Loehmann’s disastrous work history record and has since changed its hiring policy to require stricter background investigations into publicly available personnel files. The department’s use-of-deadly-force unit is currently investigating Loehmann’s shooting of Rice.

The revelations of Loehmann’s previous shortcomings have focused a national spotlight on the need for stricter background investigations of police candidates’, but less attention has been paid to the question of whether Loehmann’s psychological screening should have determined him unsuitable for the job even before his post-hire training.

Deputy Chief Jim Polak found Loehmann was “not mature enough in his accepting of responsibility or his understanding the severity of his loss of control” after he had multiple emotional breakdowns during training.

The point behind such psychological evaluations isn’t solely to determine whether an applicant has a diagnosable mental disorder, but also to flag potential recruits whose personality types and behavior are unsuited to a job in which sound judgment — including the ability to make quick decisions — is key, as is emotional stability in tense situations. It’s a determination that plays a substantial role in keeping trigger-happy cops off the streets — and thus, more people alive.

But even when candidates are selected who possess “suitable” characteristics, the job duties they must perform to fulfill their role as a cop not only have psychological consequences for the individual officer over time but also leave entire communities, especially communities of color who are disproportionately policed, with deep psychological trauma.

Psychological Evaluations Lack Standardization

Because states regulate how municipal departments operate, typically by creating state commissions or academies to determine hiring and training standards, there is currently no national standard for how police recruit candidates, how they are psychologically evaluated, or even whether or not such evaluations should be mandatory.

Truthout reviewed the websites for each state’s standards and training commission and/or state statute and found that 22 states’ commissions and/or state statutes do not explicitly mandate that a licensed psychologist administer a psychological evaluation as a minimum qualification for a potential police recruit.

Some states use vague language in their statutes, requiring only that a candidate must “be free of” any mental or emotional condition that may affect the candidates’ ability to perform their job functions. In some cases, this determination is made through the background investigation process alone. In other cases, the commission and/or state statute says that a clinical physician will make such a determination as part of a required physical examination.

State statutes such as the one in Ohio, where Loehmann shot Rice, mandate that the standards and training commissions “may” require a psychological evaluation, but the Ohio Peace Officer Training Commission does not specify that a psychological evaluation is a minimum requirement for academy training. Instead, individual police departments in the state decide whether the screenings are a required part of the department’s hiring process. Commissioners in New Jersey have delayed implementing pre-academy standards for police applicants until June of this year.

President Lyndon Johnson first recommended the use of psychological personality tests of potential police recruits in 1967 to keep pace with what had already become a standard hiring practice.

Psychological evaluations remain a common requirement throughout most large municipal police departments regardless of whether or not the state’s statute and/or standards and training commission explicitly mandate them. But even within large, urban police forces, such evaluations are inconsistently conducted, and the many tests and methods used by examiners, as well as the qualifications of the examiners themselves, vary widely. Many smaller police departments in states that do not mandate the evaluations opt out of this part of the hiring process entirely.

When departments forgo psychological screenings, the result is often violence, some of which results in police brutality litigation. Flint Taylor, a founding partner of the People’s Law Office in Chicago, tells Truthout that in many of the police brutality cases he has litigated over the years as a civil rights defense attorney, the officer involved had not had a psychological evaluation during the hiring process.

“We have been dealing with the psychological screening of police officers, and the lack of it, ever since the ’60s when I first started litigating police brutality cases,” Taylor says. “It’s a problem that police departments skirt around in one form or another.”

He pointed to many other cases he has litigated in which he felt that problem officers were kept on a police force despite displaying clear red flags and despite having been psychologically evaluated both before and after hire.

“Another aspect of it is, the firms that [police departments] hire, at least in my experience, to do the screening, lean toward the cop being OK,” Taylor says. “In the same way the system’s rigged so that [cops] don’t get disciplined when they commit these acts of torture and abuse, the psychology of it is rigged as well.”

Taylor represented victims who were tortured with electric shock under the watch of former Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge, who was released last week from a Florida halfway house after serving four-and-a-half years in federal custody for denying he knew about the systemic torture of more than 100 people in Chicago under his command decades ago.

“The kind of people that are attracted to policing are somewhat problematic to start out with,” Taylor says. “Some people [become police] because they’re idealistic and want to help and all of that, but there’s a substantial grouping of people who have violent propensities…. [Policing] attracts a lot of people who have authoritarian instincts.”

Use of psychological evaluations didn’t become common for police applicants until public outrage over the Rodney King beating in 1991.

Despite a lack of national standards governing evaluation protocols and the qualifications of those who administer them, the Police Psychological Services Section of the International Association of Chiefs of Police established the first set of guidelines for police psychologists in 1986, approving its latest revision of the guidelines in 2009. The guidelines state that a licensed, doctoral-level psychologist specializing in policing should use a number of tools including background information, assessments that have been validated by research, and personal interviews with the candidate to make a thorough determination of the candidates’ suitability as a police recruit.

President Lyndon Johnson’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice first recommended the use of psychological personality tests of potential police recruits in 1967 to keep pace with what had already become a standard hiring practice throughout the industrial economy. The most recent survey from the American Management Association of its members found that 13 percent of employers use some kind of personality assessment as part of the hiring process, including almost all Fortune 500 companies.

But the use of psychological evaluations didn’t become common for police applicants until public outrage over the Rodney King beating in 1991 forced police departments to respond by incorporating the evaluations into their hiring processes as an attempt to lower the increasing costs of police brutality litigation.

The field and practice of police psychology is still a new and emerging specialization in psychology, officially recognized only recently by the American Psychological Association (APA) in 2013. The APA’s committee on professional practices and standards for police psychology is currently in the process of drafting guidelines for all mandated assessments.

But guidelines such as these are only a suggestion, and licensed police psychologists, as with Cosner in his evaluation of Loehmann, must often conduct their screenings in a rush to meet official hire dates.

Former Cop Calls for Greater Standardization

Criminal justice professor and mental health specialist Dr. M.L. Dantzker, a former police officer in Fort Worth, Texas, wrote his doctoral dissertation on the role psychologists’ play in the pre-hiring screenings of police recruits.

In 2011, he wrote a journal article for the APA underlining the need for consistency and standardization in pre-employment psychological screenings for police applicants.

Dantzker cites his own experience in taking a psychological evaluation in Texas, where the state requires only that a psychologist use two personality tests in evaluating a candidate, as an example of how different each state’s standards can be. “That’s all they required us to do, basically, is just that,” Dantzker tells Truthout.

Despite the Association of Chiefs of Police’s guidelines, there remains no informal consensus as to what protocols and standards should be used and why, or which personality tests, typically in the form of multiple-choice and sentence-completion questionnaires, are most appropriate for potential police recruits.

“Every psychologist in Texas can choose whatever personality inventories they want to use and can do whatever else they might want to do, all within what the departments are willing to pay for,” Dantzker said. “That sets us up for a very, what I consider, inconsistent, unstable protocol and procedure for doing [evaluations].”

This inconsistency lends itself to a kind of loophole in which one psychologist may determine that an applicant is unsuitable, but another, using a different set of assessment tools, may determine just the opposite, potentially allowing applicants with violent tendencies into police ranks.

“You can basically go shopping for your own psychologist. It makes it even worse.”

In some cases, according to Dantzker, the candidate, who often must pay for their own evaluation, will seek out a second opinion if an initial evaluation determines the candidate unsuitable. In other cases, Dantzker says, the police department itself will seek out a second opinion to make a hire. Many departments allow the applicant to simply wait a year before re-applying for a position if an initial evaluation found the candidate unsuitable.

“You can basically go shopping for your own psychologist,” says Dantzker. “It makes it even worse.”

Furthermore, common personality assessments routinely used by psychologists vary greatly in their design, predictive validity, and what traits and target behaviors are measured. Not every test used is specifically designed with a police applicant in mind, and not all tests are designed to identify traits such as aggression in police candidates.

One of the most popular tests used by psychologists at police agencies across the nation is several versions of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), including the MMPI-2 and the MMPI-2-RF. However, Dantzker finds the commonly used test to be problematic in several aspects, possibly even discriminatory, writing that the test’s “normative data for police officers under-represents women and minorities; it elicits responses related to sexual orientation and religious attitudes; and it fails to measure … conscientiousness.”

But other psychologists contend the test’s predictive validity remains substantial and has only grown in the past five years, with additional research and the release of its newest version. They also caution that the resulting psychological profile produced is meant to be used in conjunction with other assessments and tools, such as interviews and background information, to paint a more comprehensive picture.

Still, says Dantzker, “The MMPI was really good at identifying individuals who … actually suffer from a personality disorder, but it didn’t do anything for truly recognizing whether a person had the proper traits or not to be a police officer.”

Another problem researchers point out that is not restricted to the MMPI is the simple fact that an applicant can lie on their test, answering questions in a way that purposefully paints the candidate in a more positive light.

Still another problem that most assessments have in common, Dantzker observes, is their objective of screening out unfavorable profiles, instead of trying to screen-in resilient, stable and conscientious personalities less likely to abuse the powers of their badge (at least initially). Like the lack of consensus surrounding the best protocols to use for psychological screenings, there remains no consensus as to the ideal personality profile for potential police recruits.

Dantzker has called for that profile to be developed and for additional research to determine what protocols are best for screening in police applicants based on that profile.

“We just need to do a trait survey looking at certain traits we want officers to have coming in,” Dantzker says. “But I think what would happen is, the person that would do this, who would put in the time and effort, would really want something in return from it. But there’s nothing to guarantee that people would actually use it, and I think that’s part of the problem.”

Even if police psychologists develop this “ideal police personality profile” and use protocols focused on screening-in applicants with favorable traits, the arrest powers and authority the applicant gains upon hire, and the nature of police work itself, is widely accepted by researchers to affect the personality and psychology of experienced police officers throughout his or her career.

Yet, incredibly, it’s not standard practice to re-evaluate police officer incumbents at any point post-hire.

The Psychological Effects of Authority

More than 50 years after the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology first published the results of Yale University psychology professor Stanley Milgram’s now-infamous experiment on the nature of obedience and authority, psychologists, historians and social scientists have exhibited a renewed interest in Milgram’s findings. While some have questioned Milgram’s methodology, others contend that his basic premise concerning an ordinary person’s willingness to obey authority still holds true.

People’s behavior is determined to a large extent by the situations and contexts in which they find themselves.

In Milgram’s lab, experimenters asked unknowing participants, dubbed “teachers,” to administer what they believed to be a series of electric shocks at increasing levels of intensity, ranging from 15 volts to 450 volts, to their subjects, dubbed “learners.” The learners were in on the experiment, but the teachers believed that the pre-recorded cries of pain in response to the electric shocks were real. While some participants stopped, despite the experimenter’s assurances and encouragement to continue, many others followed the experimenter’s orders, even up to the point of administering a 450 volt-shock.

Another infamous experiment into the nature of authority is also back in the news, with the premiere of a new film at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. The Stanford Prison Experiment tells the true story of Philip Zimbardo’s notorious experiment dividing up 24 college students into “guards” and “prisoners.” He put the students into a simulated prison environment, and what happened next, like Milgram’s shock experiments, would impact the field of psychology for decades to come.

Those in the position of prison guards quickly adapted to their roles — to the point that they inflicted real psychological torture on their classmates, including stripping them of their clothes and humiliating them. The experiment got so out of hand that it had to be stopped after six days, although it was originally meant to last two weeks.

Both the Milgram and Zimbardo experiments advance the idea of situationism — that people’s behavior is determined to a large extent by the situations and contexts in which they find themselves — contradicting the idea that the participant’s abusive behavior was caused primarily by the person’s preexisting characteristics.

It’s a notion that research in the specialized field of police psychology also seems to support. According to one licensed police psychologist, the psychological makeup of police applicants is not very different from that of the general population. The incidence of a diagnosable mental disorder in the general population is estimated to be between 3 to 5 percent. Likewise, the ratio of police applicants disqualified on the basis of diagnosable mental illness is in the same range of 3 to 5 percent.

But an increasing body of knowledge continues to be amassed documenting how policing can change the psychology and affect the personality of an officer throughout her or his career. Police work often puts officers in situations where, despite the officer’s intentions, they must exercise power over individuals, frequently in harmful ways, to do their job. Despite the particular merits that an individual officer may possess, abuse is often part of the job description.

Police officers often experience cognitive dissonance when performing duties that are contrary to their beliefs or internalized attitudes. Conflicting social roles can lend themselves toward more fixed attitudes to police work over time, as officers seek to rationalize internal conflicts. According to Police Chief Magazine, the magazine of the Association of Chiefs of Police, officers can “cognitively restructure unethical behaviors in ways that make them seem personally and socially acceptable, thereby allowing officers to behave immorally while preserving their self-image as ethically good people.”

Kelley evaluated Nazi leaders including Rudolf Hess, Hermann Göring, Alfred Rosenberg and others, determining that none of them possessed any diagnosable mental or personality disorders.

Milgram’s experiments, which uphold this theory of cognitive dissonance, began only three months after the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann began in Jerusalem in 1961. Milgram was trying to answer a question that loomed large in the public’s consciousness then, as it still does now, in the context of the continuing revelations about the Bush administration’s post-9/11 torture program: Could it be that those who commit atrocities and abuse are simply following orders — orders that stem from larger structures of violence and oppression?

It was a question that another, lesser-known psychologist obsessed over immediately following the Nuremberg trials, nearly 15 years before Milgram devised his frightening experiments. U.S. Army Captain and Psychiatrist Douglas Kelley began researching the psychological characteristics of those in positions of power after he was sent to evaluate the mental health of the top 22 imprisoned Nazi commanders awaiting trial in Nuremberg, Germany, on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Kelley evaluated Nazi leaders including Rudolf Hess, Hermann Göring, Alfred Rosenberg and others, determining that none of them possessed any diagnosable mental or personality disorders. His finding shocked him and led him to become a proponent of a variant of situationism long before the concept was a mainstream one throughout the field of psychology.

“[Kelley] came to believe that … it’s a human trait that many of us but not all of us, have … that given the opportunity to advance their own interest by hurting others, they’ll do it,” says Jack El-Hai, author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WWII, which chronicles Kelley’s life and work.

Kelley began researching the merits of this idea in the context of police applicants when he returned to the United States, taking interest in common people who take on positions of authority and viewing them as potentially more susceptible to abuse of power. He studied a group of police candidates at a municipal department in Berkeley, California, and determined that 23 percent of the candidates he examined were unsuitable, calling them “unstable” and “potential hazards.”

Later Kelley would come to believe that nearly a third to one-half of all U.S. police officers were psychologically unfit for policing and were likely to commit abuses under the right circumstances, becoming one of the nation’s very first advocates for strict psychological evaluations of police applicants — and stoking the ire of many police chiefs across the country.

“It seems strange and tragic almost, that so many decades after Kelley began working for these kinds of assessments to be made, that not a lot of progress has happened in the assessment of officers,” El-Hai tells Truthout.

Municipal police departments do routinely deploy what are known as “fitness-for-duty” examinations designed for experienced law enforcement officers, but it’s a type of examination that comes only after the officer has already displayed problematic behavior that could be a result of a mental disorder or other psychological issues. This type of examination is a targeted assessment of a specific individual who has exhibited credible evidence of at-risk behaviors, and like pre-employment psychological screenings, there’s no national protocol, but there are Association of Chiefs of Police guidelines.

Many police psychologists support the idea of mandatory counseling for all experienced officers over time, as well as mandatory re-evaluations of experienced officers’ psychological profiles.

But despite police departments’ reliance on this existing mechanism, many police psychologists support the idea of mandatory counseling for all experienced officers over time, as well as mandatory re-evaluations of experienced officers’ psychological profiles.

“I don’t know of a single police psychologist that would not advocate for better mental health assessment, evaluations and care,” says Dr. Andrew Ryan, who is president of the Society for Criminal and Police Psychology. Ryan also developed a personality assessment that is specifically designed for police applicants, called the R-PIQ. “Incumbent testing … is vital to having a preventative mental health program, and it does, in fact, help with the resiliency of employees.”

Ryan tells Truthout that there are some pockets of law enforcement where incumbent testing is common, but cited the cost of incumbent testing as a major barrier for municipal police departments. Former police officer Dantzker agrees with the need for re-evaluations of experienced cops during the course of their careers.

“Officers should have to undergo occasional psychological follow-ups,” Dantzker says. “We require them to qualify with their weapons at least once a year. We require that they do updates on training and everything else, but nothing psychological, which they use more … as their main tool, than anything else.”

Dantzker points to his experience of working as a police officer, noting that a culture exists within law enforcement where officers are often unwilling to seek counseling because of a climate of paranoia. He believes that mandatory counseling for all officers — as often as once a month, or once every six months — is an important step. “If everybody does that, then no one has to feel paranoid that they’re being picked out … or singled out,” he says.

But even if psychological evaluations of police applicants were 100 percent accurate when predicting “unsuitable” personality traits in candidates, and even if counseling for officer incumbents was made mandatory, the psychology of another group would still be left unaccounted for: people who are on the receiving end of policing. Entire communities would still face the deep psychological trauma that the nature of policing itself inflicts upon those deemed criminalized by the state.

The Psychological Effects of Criminalization

For four years, a collaborative research team made up of residents in south Bronx neighborhoods, psychologists, social scientists and academics from the City University of New York Graduate Center, John Jay College and other organizations, have documented community members’ everyday experiences of the New York Police Department’s (NYPD) “broken windows” policing in the 40-block community near Yankee Stadium.

The Morris Justice Project is focused on an approach that emphasizes “participatory action research,” in which researchers work closely with community members and use their findings to push for systemic change.

The group recently submitted a statement summarizing its findings to President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which was created by executive order at the end of last year. The task force will examine ways “to strengthen public trust” between police and communities.

The group found that in 2011, the NYPD had made 4,882 stops in the 42-block radius the group studied alone. In that area, 80 percent of the stops involved frisks, 15 percent involved searches, and 59 percent involved physical force. This empirical data translates to lasting emotional impacts that the experience of everyday policing inflicts, with researchers writing that the NYPD’s aggressive policing eats “away at residents’ ability to connect with each other, to socialize and build community.”

Among the researchers’ other key findings were that a majority of community members expressed fear, mistrust and anger toward the NYPD, with 63 percent of the 1,030 residents surveyed reporting that they felt targeted by police because of their age, race, sexual orientation, gender, employment or immigration status. Among the 54 percent of respondents who said their arrest and/or ticket was later dismissed in court, 52 percent said they felt depressed.

“Our motto became … ‘We are not broken windows,’ meaning that these policies of aggressive policing renders whole communities subject to criminality,” says Dr. Brett Stoudt, an assistant professor and social-psychologist in the Department of Psychology at John Jay College, who is also member of the project.

“There was just a basic feeling like [residents] were not being treated with respect, that they were being looked at already as a criminal before they had done anything wrong…. They were not being seen as human.”

Stoudt described how that sentiment can have the hardest and most lasting impact on young people of color, who overwhelmingly reported being stopped by the NYPD at 89 percent, with 25 percent reporting being stopped for the first time when they were only 13 or younger, and 34 percent reporting they were stopped for the first time between 14 and 16 years old.

“If you beat up, if you arrest young men or young women of color, that’s the stone, but the ripple-effect is the family, the school, the community, the place of work.”

Stoudt co-authored an article for the New York Law School Law Review called “Growing Up Policed in the Age of Aggressive Policing Policies,” which detailed how pervasive police surveillance — which follows young people from their homes, to the street, to their schools and back again — affects how young people behave, oftentimes causing them to change their social strategies, including changing how they dress and which routes they take.

“After they’ve been stopped, they have a representation in their heads of the neighborhood and the people watching them, assuming that they’re criminals, assuming that they’re bad kids,” Stoudt says. “Young people often grow up to feel depressed or extremely anxious or they have intrusive thoughts. They can’t stop worrying.”

The psychological effects of the criminalization can translate into profound psychological trauma, and in some communities where police abuse has been extreme, so has the resulting traumatization.

More than 20 years after former Chicago Police Commander Burge oversaw the torture of more than 100 Black men in the city, the communities left shattered by this particularly horrific manifestation of systemic abuse are still dealing with the psychological trauma.

During Burge’s trial, many victims testified to Burge’s use of cattle prods on their genitals as well as the use of plastic to suffocate them. Many said they were tortured into confessing to crimes they didn’t commit.

Civil rights defense attorney Taylor tells Truthout that many of the victims and members of the communities affected by Burge’s use of torture have experienced post-traumatic stress disorder over the decades.

Taylor’s firm recently co-organized a rally in support of a Chicago ordinance that would give $20 million to Burge’s 119 known victims.

In coalition with other community groups, the organization is also working to provide free tuition to city colleges for Burge’s torture victims — and to provide a psychological counseling center for the communities impacted.

“It’s like when you throw a rock into a pool of water, and all those rings that you see go out around it, well, that’s what affect [policing] has,” Taylor says. “If you beat up, if you arrest young men or young women of color, that’s the stone, but the ripple-effect is the family, the school, the community, the place of work.”

However the Justice Project’s Stoudt cautioned that it is important to avoid viewing communities subject to aggressive policing as simply damaged or debilitated, despite the fact that these communities do often experience many forms of significant trauma. Rather, he emphasizes, it’s these same communities who are speaking the loudest and forming the strong social movements sweeping the nation for police reform in the aftermath of the events last year in Ferguson, Missouri.

“We’re seeing an amazing set of young people rising up, getting frustrated, finding avenues of resistance and democratic discussion to push back on structures that are unfair, that are often racist” Stoudt says. “It’s not just about police — that’s too myopic. These are circuits of dispossession. This is connected to schools that are not properly resourced. This is connected to housing and neighborhoods that are being gentrified. It’s a part of a whole, which is a neoliberal political economy that is creating a great deal of insecurity in people’s lives.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.