(Image: Atlantic Monthly Press)The Devil Is Here in These Hills, James Green, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2015

(Image: Atlantic Monthly Press)The Devil Is Here in These Hills, James Green, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2015

Residents of West Virginia often complain about outsiders subjecting them to intense regional stereotyping. Certainly, during the heyday of the militant coal miner struggles, national reporters often would portray West Virginians living in coal country as “backcountry hillbillies” prone to irrational violence.

But when looking back at the mine battles of the early 1900s, West Virginia officials are as guilty of misrepresenting the state’s rich history – by way of omitting or skewing significant facts – as any outsider.

To this day, state officials conceal stories of union organizers who fought to create better lives for ordinary West Virginians. The treatment of Charles Francis “Frank” Keeney Jr. serves as a prime example of how West Virginia turned its back on its labor leaders. As president of United Mine Workers of America District 17, Frank Keeney was a driving force behind improving the working and living conditions for the state’s coal miners and their families.

But Keeney’s union organizing efforts upset the economic status quo by breaking the authoritarian grip of the coal companies. For that reason, West Virginia’s political and business establishment has not forgiven him. As punishment for his success as a labor organizer, officials have banished Keeney from official state histories and school textbooks.

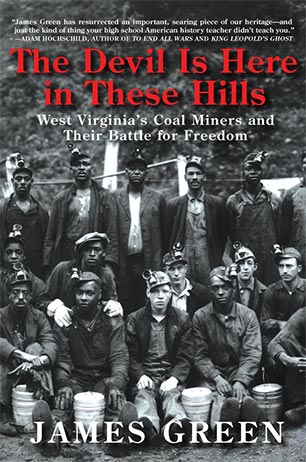

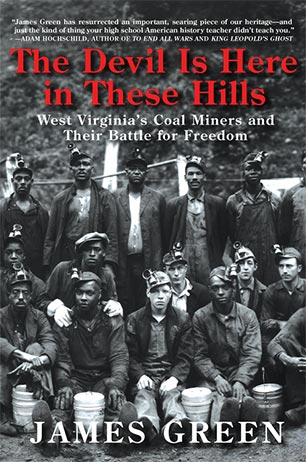

Labor historians have tried to set the record straight by writing books and articles about the battles in West Virginia’s coalfields. The most recent work to shine a light on the state’s labor wars is James Green’s captivating new book, The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom, published by Atlantic Monthly Press. Green describes The Devil Is Here in These Hills as the first book to fully chronicle West Virginia miners’ militant struggles for emancipation starting in 1892, when the first United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) organizers appeared in coal camps, to the early part of the New Deal, when union forces emerged victorious after 40 years of struggle.

In the book, Green weaves a story about the rise of the militant coal unions around the life of Keeney. As a UMWA member, Keeney played a crucial role in the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike of 1912-1913. And as president of UMWA District 17, Keeney led the charge against the mine owners during the strike of 1920-1921, including the Battle of Blair Mountain. These actions provided a model for the militant industrial strikes that rocked the US in the 1930s and laid the groundwork for the reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Congress to head off the rampant revolutionary fervor.

Politicians Still Covering Up the Truth

Aside from telling riveting stories of labor battles, Green also dissects how the mine wars are interpreted today. He explains that Keeney’s great-grandson, C. Belmont “Chuck” Keeney, grew up in the Mountain State but never read a word about his great-grandfather or the mine wars in his eighth grade state history textbooks. When he studied history in college, he found no mention of the mine wars in his US history textbooks or even in the surveys of American labor history he read while attending graduate school at West Virginia University.

One reason US historians have neglected to chronicle the mine wars in southern West Virginia, according to Green, may be that historians who sympathize with the union cause are reluctant to focus on what happened when union members picked up arms to fight back against the usually superior forces mobilized by their employers. These sympathetic historians tend to focus their attention on incidents when workers were the victims of violence like the railroad workers’ uprising of 1877 and the Ludlow massacre of 1914.

Similar to Chuck Keeney’s experience, novelist and West Virginia native Denise Giardina does not recall any mention of the mine war events in school. Giardina, who grew up in the coalfields where the wars were fought, later learned about the battles in obscure self-published accounts.

Green writes that Giardina was astonished to learn after her school years that “West Virginians had fought back against their oppressors.” She now understands that state and local officials wanted to cover up the truth. The reason, according to Giardina, was clear to anyone who grew up in a region where “the coal industry still controlled all.” She later wrote a novel, Storming Heaven, based on the coal wars in southern West Virginia from 1890 to 1921.

“More Americans probably learned about the mine wars from Giardina’s fictional account than from all previous works of scholarship taken together,” Green states.

Green’s beautifully written account of the mine wars may eventually match Giardina’s success in reaching a wide audience. WGBH, the PBS station in Boston, acquired the rights to The Devil Is Here in These Hills. His book will be the basis of a television documentary to be broadcast in PBS’s “American Experience” series.

Once he decided to write the book, local experts warned Green, a professor of history emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, about the pitfalls of outsiders writing Appalachian history. But residents placed their trust in Green, an acclaimed labor historian, to tell a fair story about West Virginia. Many residents were generous with their time, sharing their knowledge of the labor wars.

Mother Jones Takes Miners Under Her Wing

During his research, Green learned that many West Virginia residents also had placed their trust in another outsider, Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, who was a paid organizer for the UMWA and spent extensive periods traveling through the state’s coalfields.

Even as an outsider and a woman, Mother Jones attracted the devotion of West Virginia’s miners with her fiery spirit and willingness to make great sacrifices for them, including spending 85 days in confinement for her role in organizing miners during the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike. At a UMWA convention in early 1901, Mother Jones told the delegates gathered in Indianapolis that West Virginia’s miners worked and survived in wretched conditions and were oppressed by mine owners who make the czar of Russia seem like a gentleman. Green writes that Jones found “these mountain miners” to be “some of the noblest men” she had “met in all the country.”

Jones met Frank Keeney when he was only a teenager, describing him as a “bright-eyed little fellow.” She took him under her wing and would play an influential role in his rise as a union leader. Keeney grew up in the Cabin Creek community of Eskdale in Kanawha County, about 20 miles southeast of Charleston. As a young miner at the turn of the century, Green writes, Keeney understood the extreme danger every time he went underground and learned to honor the wisdom of the most experienced miners. West Virginia’s mine safety laws were the weakest in the nation. Hundreds of miners would die each year in the state’s coal mines during the first half of the 20th century.

At the time of the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike of 1912-1913, Keeney and his comrades, according to Green, drafted a list of demands that included the right to free speech and peaceable assembly. They also demanded that the mine owners remove the private security guards stationed in the region. Even though their demands did not include a wage increase, Keeney and the others were immediately fired from their jobs and evicted from their company-owned houses. After vacating their home, Keeney and his family joined other strikers in a tent camp near Eskdale.

Though suffering from malnutrition and other ailments, the strikers found enough strength to wage their battle against the authoritarian rule of the mine owners. Eventually, West Virginia Gov. William Glasscock sent the state National Guard to the region to put an end to fighting between strikers and the coal operators’ private guards. The governor asked the commander of the state National Guard, General Charles Elliott, to file a report from the field. Green found the title for his book inside the report Elliot submitted to the governor. Elliott wrote that the mine owners’ quest for “dividends” had led to the degradation and impoverishment of their employees. “The devil is here in these hills, and the devil is greed,” Elliott told the governor.

Keeney and his fellow mine workers did not let their poor living conditions distract them from their goal of creating a more democratic and inclusive union. Tired of the employer-friendly UMWA District 17 leaders, Keeney formed UMWA District 30 on Cabin Creek. According to Green, the organization was based on two principles: democratic control by the rank and file and the socialist ideal of workers’ control over industry.

The national head of the UMWA took notice of Keeney’s success in rallying miners and decided to suspend the incumbent officers from District 17. A new election was called, and Keeney was voted in as president of the district.

Treating Black and White Miners as Equals

At the time, the UMWA, unlike other trade unions, treated Black and white miners as equals. “The UMWA’s leaders adopted a policy of inclusion, even as a color line was being drawn across the land,” Green explains. The UMWA constitution stated: “No local union or assembly is justified in discriminating against any person in securing or retaining work because of their African descent.”

Along with their strong representation in the rank and file, African Americans also were hired as UMWA organizers. But Green reports that Black miners still could not completely shake the feelings of slavery in the coalfields. “They were now free to leave their place of employment, and in West Virginia, they were free to vote. But like their white cohorts, Black miners found that something of slavery remained in the lives of men who sold their labor and sacrificed their liberty for the right to work for a coal company and live in a company town under the watchful eye of deputy sheriffs and private detectives,” he writes.

The UMWA District 17 region covered most of West Virginia’s coal mines. In 1916, when Keeney was elected president of the district, West Virginia coal annual production totaled about 90 million tons, more than double the total from 10 years earlier. The mine operators benefited from the miners’ discipline and courage, which made them “ideal industrial soldiers,” Green writes. “On the other hand, the qualities the men forged in underground combat with the elements – bravery, fraternal fealty and group solidarity – hardened them for aboveground combat with their employers.”

In the early 1900s, socialism had gained tremendous appeal to many Americans, especially among the working class. Socialists controlled town governments across West Virginia, and the state was home to several socialist newspapers. Keeney and his top lieutenant Fred Mooney managed the union along socialist principles.

“Because experienced colliers understood the technology and labor processes of mining far better than the owners, the Socialists and many others in their ranks believed the miners could operate the coal industry cooperatively and manage it more rationally and safely than the capitalists did,” Green writes.

Union Leaders Rally Around the Flag

Upon the United States’ declaration of war on Germany and its allies in 1917, Keeney and the union rallied around the war effort. Mother Jones, who had remained an active organizer in the coalfields, also was a strong supporter of the war. At a UMWA convention in January 1918, Jones told the union delegates, “When we get into a fight I am one of those who intend to clean hell out of the other fellow, and we have got to clean the Kaiser up.” She insisted the union members “stand behind this nation and fight to the last man.”

The union’s support for US entry into World War I put its leaders in conflict with other socialists and radicals who condemned the war effort. The union leaders “chose to look away as old comrades in the Socialist Party and the IWW [Industrial Workers of the World] suffered extremely harsh punishment for their opposition to the war,” Green writes. “Ralph Chaplin, the Wobbly who had supported and publicized the Paint Branch-Cabin Creek strike, was rounded up along with a hundred other IWW activists.” Socialist Party leader and four-time presidential candidate Eugene V. Debbs was arrested and sentenced to a 10-year prison term for delivering a “treasonous speech” in which he declared that it had become “extremely dangerous to exercise the constitutional right of free speech in a country fighting to make the world safe for democracy.”

Keeney and his associates, according to Green, assumed their proclamations of loyalty to the war effort would shield them from “the repressive forces unleashed by the war effort.”

The government did indeed leave Keeney alone during the war. But government authorities adopted a different stance toward Keeney after the mine wars of 1921 and the Battle of Blair Mountain. West Virginia officials brought charges of treason against Keeney and other leaders. The charges were later dismissed, but John L. Lewis, the legendary head of the UMWA, had grown tired of Keeney’s militant tactics. In 1924, after winning acquittal in a politically motivated murder trial related to the union’s militant actions, Keeney resigned his position as District 17 president.

“Keeney’s insistence on union democracy, his socialist beliefs, and his willingness to wage war on the mine guards and defy his own government all clashed with Lewis’ brand of conservative business unionism and his autocratic approach to union leadership,” Green writes.

Frank Keeney’s Legacy

Today, coal is still king in the minds of most West Virginia politicians. Unlike in Kentucky, where political leaders have approved state-sponsored economic transition efforts for the coal industry, West Virginia’s political establishment has pushed residents to fend for themselves in the midst of coal’s decline over fears of angering the coal companies.

“People are afraid of being seen as anti-coal because it is such a dominant political force,” said Jeff Kessler, a West Virginia state senator and gubernatorial candidate who tried (but failed) in 2014 to get support for a publicly funded jobs initiative similar to one pushed by political leaders in Kentucky.

In a 2009 blog post, Chuck Keeney wrote that a friend asked him in a joking manner, “You think if Frank Keeney were alive today that he’d have a Friends of Coal bumper sticker?” Chuck Keeney responded that Frank Keeney “was no Friend of Coal, but he was a friend of coal miners. There is a big difference.”

In 2011, Chuck Keeney was part of a 50-mile protest march to Blair Mountain in Logan County. The march was called in reaction to industry plans to use mountaintop removal mining at the site. In 2009, the US Department of the Interior listed the Blair Mountain Battlefield on the National Register of Historic Places. But nine months later, the federal government backtracked and de-listed the site from the register after receiving pressure from the coal industry.

The marchers planned to follow the same route that the miners had taken on their 1921 march into company territory on a mission to free their fellow workers in nearby Mingo County. The protesters of 2011, Green writes, were marching to stop a mining company from blowing the top off Blair Mountain so that its machines could strip-mine its coal deposits. The marchers included local residents, retired coal miners and environmental activists. They wore red bandannas like the union members had in 1921.

The marchers were nervous because during an earlier reenactment of the 1921 miners’ march, protesters, including former West Virginia Congressman Ken Hechler, were attacked and beaten. The 2011 march was free of violence, but residents standing along the roadside screamed obscenities at the marchers and called them tree huggers and job destroyers.

From his vantage point as a West Virginia resident, Chuck Keeney viewed the 2011 march not only as a protest against mountaintop removal but as an attempt to recover the lost memory of a struggle for freedom and justice his great-grandfather led long ago.

We have 9 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.