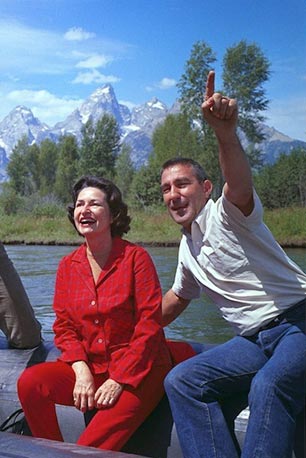

Stewart Udall, then secretary of the interior, and Lady Bird Johnson in Grand Teton National Park, in 1964, the year before the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) was created. The LWCF later paid for acquiring inholdings within the park. (Photo: Robert Knudsen / LBJ Photo Archive)This story was originally published on October 1, 2015, at High Country News (hcn.org).

Stewart Udall, then secretary of the interior, and Lady Bird Johnson in Grand Teton National Park, in 1964, the year before the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) was created. The LWCF later paid for acquiring inholdings within the park. (Photo: Robert Knudsen / LBJ Photo Archive)This story was originally published on October 1, 2015, at High Country News (hcn.org).

In July, Montanans celebrated the addition of 8,200 acres, known as Tenderfoot Creek, to the Lewis and Clark National Forest. Most of the $10.7 million cost was paid for by the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund, which uses oil and gas royalties for conservation and recreation projects.

But last month, the 50-year-old fund, widely viewed as one of the nation’s most popular and most successful land conservation programs, was allowed to expire completely. Despite broad bipartisan support, and despite a deadline that was no surprise to anyone, Congress failed to take action to reauthorize it. That means that offshore oil and gas producers will no longer be paying into the chest that funds the program – and now that the funding connection has been broken, reinstating it will be very difficult, especially given the tone of this Congress. Instead, lawmakers will be dickering over how to divvy up former LWCF appropriations, which will now be going into the general treasury.

Earlier this summer, dozens of representatives on both sides of the aisle had signed a letter in support of the perpetually underfunded program, which has conserved more than seven million acres so far. LWCF purchases wildlife habitat, buys private inholdings within wildernesses and national parks, preserves cultural heritage sites, provides public access for fishing and hunting, and pays for urban parks, playgrounds and ballfields. (The Center for Western Priorities created an interactive map showing how LWCF has made national parks whole by paying to buy inholdings from private landowners.) And if put to a straight-up vote, reauthorization would pass both the House and Senate with bipartisan majorities.

But action on LWCF was derailed by far-right opposition, led by Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah, House Natural Resources chairman, reflecting the anti-public-land and anti-federal sentiments afoot in some quarters of the West. Bishop is floating his own reforms to the program, which include redirecting most of the money to state and local projects (in the 1970s, Congress removed a requirement that states get 60 percent of LWCF funding).

The sunsetting of the LWCF was greeted with dismay by conservationists and by many of the legislators from both parties who have long supported it, including Republican Sen. Steve Daines and Rep. Ryan Zink of Montana. At a breakfast organized by the Backcountry Hunters and Anglers in support of LWCF, Daines said, “I personally don’t think Rob (Bishop’)s view, and others have said this, necessarily reflects probably where most of the conference is now.”

Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Arizona had some scathing words for the House in a statement: “You can see just how extreme some House Republicans really are when a popular conservation program with a spotless, fifty-year history of bipartisan reauthorization expires thanks to their partisan games. They can’t pass a highway bill, they can’t fund the government, they’re still struggling with a defense bill, and now they insist that LWCF funding has to stop.”

Congress is authorized to allocate up to $900 million annually to LWCF, not from taxpayers’ dollars but from royalties paid by energy companies drilling on the Outer Continental Shelf. It rarely gives the fund anywhere close to that, though, and in recent years has sent about two-thirds of the allocation to the general treasury. As a result, the program has accumulated a $20 billion IOU, which Rep. Bishop cites as a reason not to continue funding it. But that money isn’t just lying around waiting to be spent, explains Mary Hollow, executive director of Montana-based Prickly Pear Land Trust, in the Helena Independent Record: “This is a paper account with nothing in it – there are only cobwebs,” she said. “The $20 billion has already been spent – diverted to fund other things … it’s inaccurate and unrealistic to think that if LWCF expires and we lose our authorization and revenue source that it would be business as usual.”

So what’s likely to happen next? “This is a sad day for everyone who cares about our national parks and outdoor conservation, recreation and wildlife. Congress has broken an enduring promise to the American people,” said Alan Rowsome, senior director at the Wilderness Society and co-chair of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Coalition, in a statement. But the coalition, the outdoor recreation industry, other conservation groups, and Backcountry Hunters and Anglers aren’t just mourning the program’s loss – they’ll be kicking efforts into high gear to get the LWCF reauthorized as quickly as possible.

And Congressional supporters are looking for those opportunities. Sen. Daines told the breakfast meeting that reauthorization has “a higher probability if we attach it to another piece of legislation,” so they’ll be looking for some piece of must-pass legislation before the end of the year, like the omnibus spending bill or a highway and transportation bill. He and Sen. Jon Tester, D-Montana, have also cosponsored legislation introduced by Sen. Richard Burr, R-North Carolina, that permanently reauthorizes the program, and Tester cosponsored a bill that goes farther, locking in the full appropriation of $900 million so it can’t be siphoned off for other uses.

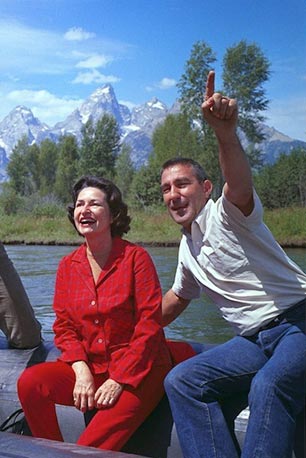

Approximately 8,000 acres, known as Tenderfoot Creek, was purchased this summer with primarily LWCF dollars and some non-federal funds, and added to the Lewis and Clark National Forest. (Photo: US Forest Service)

Approximately 8,000 acres, known as Tenderfoot Creek, was purchased this summer with primarily LWCF dollars and some non-federal funds, and added to the Lewis and Clark National Forest. (Photo: US Forest Service)

Sen. Grijalva and Rep. Mike Fitzpatrick co-sponsored a permanent reauthorization bill as well. When introducing it, Grijalva said, “Drawing out the uncertainty over the program’s funding every few years serves no one, especially when our constituents so strongly believe in the LWCF’s mission and value to the country. We should make it permanent, avoid prolonged budget battles and get back to the business of protecting our natural spaces. Anything less is a disservice to the legacy of Teddy Roosevelt and the generations of Americans who gave us the many beautiful American landscapes we enjoy today.”