The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) is an organization shrouded in mystery. This may be due mainly to the fact that the majority of people don’t even know of its existence. According to the BIS itself, the main purpose of the Bank is “to promote the cooperation of central banks and to provide additional facilities for international financial operations,” and to “act as trustee or agent in regard to international financial settlements entrusted to it under agreements of the parties concern.”

What this means is that the BIS simply enables central banks to work with one another. While its purpose has changed and evolved over the decades, the BIS has always been a club for central bankers – and in many ways it has aided some countries more than others. The Bank has a Board of Directors that “may have up to 21 members, including six ex officio directors, comprising the central bank Governors of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States. Each ex officio member may appoint another member of the same nationality. Nine Governors of other member central banks may be elected to the Board.”

The BIS also has a management wing in the form of a General and Deputy General Manager, both of whom are responsible to the Board and supported by Executive, Finance, and Compliance and Operational Risk Committees. However, its purpose has changed and evolved over the decades, however, it has always been a club for central bankers, yet in many ways it can aid some countries more than others.

How It Started

The origin of the BIS is in the United States, specifically New York City. The individuals involved were international bankers who, despite past differences, “worked together to establish a world financial order that would incorporate the federal principle of the American central banking system.” Among them were figures like Owen D. Young, J. Pierpont Morgan, Thomas W. Lamont, S. Parker Gilbert, Gates W. McGarrah, and Jackson Reynolds, “who, in conjunction with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, sought to extend the principle of central bank cooperation to the international sphere.”

Before delving further into the creation of the Bank and purpose it has served, and for whom, it’s wise to examine some of the more notable of these individuals to better understand why they got involved in the creation of an international bank.

Owen D. Young was already well placed for the US government; “with the cooperation of the American government and the support of GE, [he] organized and became chairman of the board of the Radio Corporation of America” and “in subsequent years he engineered a series of agreements with foreign companies that divided the world into radio zones and facilitated worldwide wireless communication.” Young had a strong belief that global radio service and broadcasting were important for the advancement of civilization. In 1922, he became chairman of General Electric, and along with GE President Gerard Swope, “urged closer business-government cooperation and corporate self-regulation under government supervision.”

During the 1920s, Young became involved in international diplomacy as the foreign affairs spokesman for the Democratic Party. At the behest of then-Secretary of State Charles Evan Hughes, Young and the banker Charles Dawes were recommended to the Allied Reparations Commission to deal with the breakdown in Germany’s reparations payments following World War I. The Commission resulted in the Dawes Plan, which allowed that “Germany’s annual reparation payments would be reduced, increasing over time as its economy improved; the full amount to be paid, however, was left undetermined. Economic policy making in Berlin would be reorganized under foreign supervision and a new currency, the Reichsmark, adopted.”

Young viewed improving the world financial structure as important to “the very survival of capitalism.” Furthermore, wrote Frank Costigliola in “The Other Side of Isolationism: The Establishment of the First World Bank, 1929-1930,” Young “sought rather the ‘economic integration’ of the world which would prepare the way for ‘political integration’ and lasting peace.”

John Pierpont Morgan, Jr. was already ensconced in the world of international banking, having inherited the JP Morgan Company from his father. During WWI, the House of Morgan worked hand-in-hand with the British and French governments, engaging in a number of tasks such as floating loans for the two countries, handling foreign exchange operations, and advising officials of each respective country.

Not only Young and Morgan, but each of the above mentioned individuals were heavily involved in politics and banking – and therefore had a personal interest in the creation of a global bank. The plan also fit into the US government’s own policies, writes Costigliola, as Washington wanted to “[keep] aloof from the political entanglements in Europe while safeguarding vital American interests by means of unofficial observers or participants.” The Federal Reserve was also interested in the creation of the BIS, as it would “[promote] both the ascendancy of New York City in world banking and the reconstruction of a stable and prosperous Europe able to absorb American exports.”

Thus, the idea of an international bank didn’t occur in a vacuum but rather, according to Beth A. Simmons, author of the article “Why Innovate? Founding the Bank for International Settlements,” its creation “was inextricably tied to the problem of German reparations in the context of Germany’s overall debt burden during the 1920s.” A slowdown in international lending to Germany began in 1928 as markets became extremely worried about the internal politics of the Weimar Republic. Due to the breakup of a center coalition government, and with the Social Democrats needing support from right-wing parties, the political situation began to fall apart as “government stability [was] threatened whenever budget debates exposed the basic social divide of unemployment insurance and increased industrial taxation on the one hand versus spending austerity and tax cuts on the other.”

Weimar’s budget problems came on the heels of the Reparations Commission determining that Germany’s total reparations came to $33 billion, which was twice the size of the country’s total economy in 1925. As long as foreign capital kept coming into Germany, things might have remained fine; but that situation changed in 1928. Between February 1929 and January 1930, negotiations were carried out to reschedule Germany’s reparations payments. “These negotiations were initiated by central bankers and private actors,” writes Simmons, “who were the first to link problems in the capital market with the need to reorganize Germany’s financial obligations.” Thus, it should come as no surprise that many of the individuals involved in creating the BIS were central bankers themselves, or engaged in international affairs and finance to some extent.

The idea for an international bank had already been explored to some extent by people like the economist John Maynard Keynes. But the idea for the bank truly took off during the Young Conference in 1929, when the Allies were attempting to exact Germany’s reparations debts for WWI. Belgian delegate Emile Franqui bought up the possibility of having a settlement organization to administer the reparations agreement, and the very next day, Hjalmar Schacht, president of the Reichsbank and chief German representative at the conference, presented a proposal to establish just such an organization.

The Bank for International Settlements would act as a lender to the German central bank in case the German currency weakened and the government found itself unable to make the reparations payment. In addition, it would give steps for how to proceed in the case of German default. According to Simmons, “if Germany did not resume payments within two years, the BIS would propose revisions collectively for the creditor governments (which would only go into effect with their approval)” and “the bank was responsible for surveillance and informing the creditor countries about economic and financial conditions in Germany.”

The US State Department had wanted a settlement to Germany’s reparations woes, as economic adviser Arthur N. Young observed that “a final reparations settlement [would] promote both political and economic stability in Europe, and thus tend to be of advantage to the United States.” But the US government as a whole didn’t want any type of linkage between reparations and war debts – due to the fact that, while each of the Allied nations were demanding reparations from Germany large enough to cover the country’s debts to the US, having such a linkage would mean that “Germany’s refusal or inability to pay that amount would put Washington in the position of having to agree to a debt reduction or bear the opprobrium and suffer the consequences of opening the door to financial chaos,” according to Costigliola.

However, several other countries had their own interests in stake in the creation of the BIS. French Prime Minister Raymond Poincare promised the French public that the reparations would cover the country’s debts to both the US and Britain, as well as cover the war damages. France was also interested in reaching an agreement on German debts, since they were developing trade interdependence with the Germans and stability was needed.

Britain also wanted to use the BIS as a means to ensure that the Germans would pay on their debts as scheduled. The Bank of England supported the creation of the BIS, wrote Simmons, “because of its potential role in stabilizing the position of the pound in the international monetary system. Britain’s relatively small gold reserves made it difficult to defend the pound without international monetary cooperation and the willingness of smaller powers to hold foreign exchange as reserves instead of gold.”

The meeting in Baden, Germany, in October of 1929 to draw up final plans for the BIS saw the heavy presence of US finance in the form of Melvin Traylor, from the First National Bank of Chicago, and Federick Reynolds, from the First National Bank of New York. There, the two men nominated Gates W. McGarrah, chairman of the board of the New York Reserve Bank, for the officer of BIS President. When the Bank of England leadership expressed anger, claiming the European public wouldn’t find the American domination of the Bank acceptable, they was effectively told that if they wanted American participation in the BIS, it would have to be on American terms. They agreed to appoint Pierre Quesnay of the Bank of France as the bank’s general manager, and the BIS was officially founded on May 17, 1930.

A Rocky Beginning

The role of the BIS quickly changed with the onset of the Great Depression, when it became unable to “play the role of lender of last resort, notwithstanding noteworthy attempts at organizing support credits for both the Austrian and German central banks in 1931.” Due to the Depression and Germany’s inability to pay, the issue of reparations went off the table. The crisis was further compounded when countries like Britain and the US began devaluing their currencies (i.e. printing more money). The BIS attempted numerous times to end the exchange rate instability by restoring the gold standard, and according the bank itself, “the BIS had little choice but to limit itself to undertaking banking transactions for the account of central banks and providing a forum for central bank governors to help them maintain contact.”

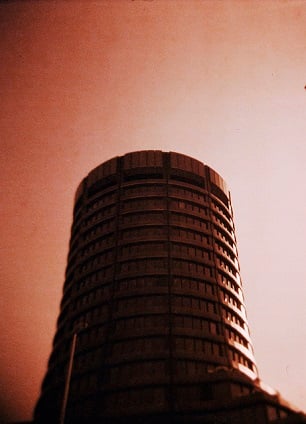

During the Second World War, all operations at the BIS were suspended. The situation again became dicey for the Bank once the guns stopped firing. Immediately after WWII, the global economic landscape had massively changed; a new system was needed, and in July of 1944 over 700 delegates from the Allied nations met at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, NH, for the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, which “agreed on the creation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and an International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (BRD), which became part of the World Bank,” writes Adam Lebor in his New York Public Affairs article “Tower of Basel.”

Under the agreements, the IMF would pay attention to exchange rates and lend reserve currencies to nations in debt. A new global currency exchange system was created where all currencies were linked to the US dollar and, in exchange, the US agreed to fix the price of gold at $35 an ounce. All of this meant that there would be no need for currency warfare or manipulation, – proving a threat to the BIS, because if the IMF was to be the center of the new global financial order, what need any longer was there for a BIS?

Wilhelm Keilhau, a member of the Norwegian delegation, even went so far as to propose a notion to eliminate the BIS. However, several other European nations noted the bank’s importance to finances on the European continent, and soon the move to eliminate it was rescinded.

Matters remained stable until the 1960s and 70s, but as the Bretton Woods system of “free currency convertibility at fixed exchange rates” coincided with a massive increase of international trade and economic growth, cracks began to show. The British currency was weak and, more importantly, the gold parity on the US dollar was straining due to “an insufficient supply of gold and from the weakening of the US balance of payments.” The Bretton Woods system collapsed in August of 1971, but the system of “managed floating” was created in its place, which allowed for flexibility of exchange rates within certain parameters. Later in the 1970s, the situation became still more dire with the creation of OPEC and the subsequent rise in oil prices, along with the Herstatt Bank failure.

The Herstatt Bank was central for processing foreign exchange orders, but German regulators withdrew the bank’s license forcing the bank to close up shop on June 26, 1974. Meanwhile, “it was still morning in New York, where Herstatt’s counterparties were expecting to receive dollars in exchange for Deutsche marks they had delivered” and when Hersttat’s clearing bank Chase Manhattan refused to fulfill the orders by freezing the Herstatt account, it caused a chain of defaults. It was this problem that led to the creation, in conjunction with the G-10 countries and Switzerland, of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, whose goal was to set the global standard for bank regulation and to provide a forum for bank supervisory matters.

Yet this newly created stability was short-lived as well. Oil prices had quadrupled in November of 1973, leading to stagflation, an increase in balance of payment imbalances, and major shocks in international banking. The Euro-currency markets grew as they began to be utilized more and more by OPEC countries – and oil-producing nations invested in European money markets, greatly increasing the money of European banks, which they thus could lend.

The European Coal and Steel Community began loaning money to developing nations at a faster and faster pace, and while this was largely beneficial to the world economy at the start, “it also implied that the international banking system was faced with an increase in country risk,” as many of the countries receiving loans were also getting more and more into debt. This concerned the then-BIS economic advisor Alexandre Lamfalussy, who warned of a threat of a crisis specifically focused on credit, saying in a 1976 speech that from “[looking at] the continuous growth of credits, the spread of risks to a large number of countries, and the change in the nature of credits, I draw the conclusion that the problem of risks has become a very urgent one.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.