A 100,000-acre spruce beetle kill drapes this alpine mountain park like a heavy wool blanket. Except for a green strip of young trees along the old logging roads that crisscross forested areas like these, 90 percent or more of the rest of the forest has been killed. Groundhog Park, La Garita Range, Rio Grande National Forest, south central Colorado, elevation 11,000 feet. Background: Mesa Mountain, elevation 12,994 feet. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

A 100,000-acre spruce beetle kill drapes this alpine mountain park like a heavy wool blanket. Except for a green strip of young trees along the old logging roads that crisscross forested areas like these, 90 percent or more of the rest of the forest has been killed. Groundhog Park, La Garita Range, Rio Grande National Forest, south central Colorado, elevation 11,000 feet. Background: Mesa Mountain, elevation 12,994 feet. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

We were awash for 19 days in a tumultuous sea of mountains and forests, drifting a course through the heart of the US Rockies on a 6,000-mile journey of observation. Our film, What Have We Done, the North American Pine Beetle Pandemic, was released in 2009. It was the story of what is now 89 million acres of forest across the North American West that have been attacked by native insects. These insects had been driven to unprecedented numbers by warming that is twice or more the global average. Most of the trees in impacted forests were killed in the wake of the beetles.

It has been four years since the Climate Change Now Initiative’s last post-film observation in 2010. Our epic crossing was different on that final journey. The mountainsides of impacted forests were not predominantly bright red. Some were red. Some were brown. And ghost forest of gray needleless conifers at times spread to the horizon.

Climate scientists have long warned that insect infestations will be greater on a warmer planet.

My wife was along on this trip, on what is usually a solo operation. It was the first of these incredible journeys on which she has been able to accompany me. At an average of 285 miles per day, this was a little tamer than most, but still a grueling but exquisitely beautiful 21-day adventure across the Rockies.

The mountain pine beetle – a single species of native beetle – had attacked an area that was 20 times larger than ever recorded. From 60 to nearly 100 percent of the trees in those forests were killed. It began in the late 1990s and was widespread from New Mexico to British Columbia. The reasons for the attack were many but largely, warming has virtually eliminated the cold temperatures that have previously kept beetle populations under control.

Lodgepole pine, the original target, once made up about 20 percent of western North American forests. They haven’t disappeared, but their ecosystem is in shambles and warming will very likely preclude the maturation of new lodgepole forests to take their place.

Dendroctonus ponderosae, the mountain pine bark beetle on a domino. Up to 10,000 of these beetles can attack a single tree. The first year, their larvae eat out galleries between the bark and the sapwood, cut off the tree’s circulation and it dies. The second year, the mature beetles fly and the tree turns red or brown. The third year, the needles brown more and begin to fall. By the fourth year, the trees are skeletons of grey sticks. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Dendroctonus ponderosae, the mountain pine bark beetle on a domino. Up to 10,000 of these beetles can attack a single tree. The first year, their larvae eat out galleries between the bark and the sapwood, cut off the tree’s circulation and it dies. The second year, the mature beetles fly and the tree turns red or brown. The third year, the needles brown more and begin to fall. By the fourth year, the trees are skeletons of grey sticks. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

This attack has dwindled to 1.6 million acres in the United States as of 2014 reports. The mountain pine beetles are running out of food. The attack has now evolved to new, different forest insect pests in other types of trees. The scale of these new attacks, like the last attack, appears to be like nothing seen before.

This is just the beginning. The first to fall are the most vulnerable and least able to adapt. Our forests at altitude are some of the most fragile and vulnerable ecosystems in existence. However, their disappearance is normal. It happens every time we have an abrupt climate change.

Berserk Beetles Attack

The beetles normally take two years to develop but a longer warm season has doubled their development rate to only a year. Climate scientists have long warned that insect infestations will be greater on a warmer planet. This attack is how that prophecy begins. Half the forests in British Columbia have fallen victim – 44 million acres in total if we include Alberta. This is an area 20 times bigger than Yellowstone National Park, bigger than New England, New York and New Jersey combined. There were so many beetles at the peak in the mid- to late 2000s that strong winds transported them 100 miles over the spine of the Rockies. It was said, “they fell like rain.”

Central Colorado, north of the La Garita Range, along the northeastern edge of the 2 million-acre spruce beetle attack in this area. Most areas above 10,000 feet in south central and southwestern Colorado are seeing a lot more heavy to exceptional kill. Sage Park, Rio Grande National Forest, elevation 10,200. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Central Colorado, north of the La Garita Range, along the northeastern edge of the 2 million-acre spruce beetle attack in this area. Most areas above 10,000 feet in south central and southwestern Colorado are seeing a lot more heavy to exceptional kill. Sage Park, Rio Grande National Forest, elevation 10,200. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

During the peak of the attack, all across western North America there were so many pine beetles that they began attacking other species like fir and spruce. The total of 89 million acres of mortality, at a conservative 80 trees per acre, amounts to 7 billion red conifers. And all this is due to only 0.74 degrees Celsius of warming by 2014, on average across the globe.

The beetles attack old, stressed trees in dense stands during drought. If conditions are optimum, the attacks can grow to millions of acres over 10 or 15 years. There is talk about how fire suppression has increased risks of beetle attack and it was especially loud in the early days of the attack, but now that most of the lodgepole forests across North America have been heavily impacted, this talk is revealing itself to be less and less meaningful.

The total lower 48 footprint of the mountain pine beetle alone, from 2000 to 2014, was 25.1 million acres.

Further separating recent events from history, there is no record of the attack crossing the Continental Divide, spreading to such wide-ranging geographic regions across the West or evolving to where the beetle was attacking more than just a single species of tree at a time. US Forest Service and logging industry management strategy for post-attack in the early days was that the trees would remain standing and ready for logging for decades. What we have found is that after three or four yours the wood gets too brittle to use for anything but pelletized fuel and after a few more years the trees’ tops break off in the logging process and hazards become too great to salvage any more wood.

Young trees are sprouting up in the oldest kills because the young are very vigorous. But their ecosystem has changed. These forests are no longer located in the climate where they evolved. In our current and exponentially warming climate, young lodgepole in these impacted forests will inevitably succumb to beetles, disease or fire before they mature. What remains will be ecosystem chaos.

Ecosystems Collapse Noiselessly

This forest collapse phenomenon is not new and it is not abnormal as far as forest occurrences go. This is one of the few ways that mature forests regenerate. At its most extreme, like is happening now, it is an ecological reordering that happens every time there is abrupt climate change. Our climate is now warming beyond the evolutionary range of the forests in the North American West. Ecosystems are collapsing, very likely in exactly the same way that has happened over 20 times in the last 100,000 years during previous abrupt climate changes. What regrows, if we can stabilize our climate, ultimately will be quite different because it will grow back in a different climate.

Whitebark pine kill, Sylvan Lake, southeast Yellowstone. Eastgate continues to show new pine beetle kill in the badly hit whitebark pine forest with what looks like redkill from pine beetle. There is budworm in this area too, and the white trunks stand out. In 2009, there was a big burn just east of here. The upper left mountain flank in this image shows a little burn scar to compare with the beetle damage. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Whitebark pine kill, Sylvan Lake, southeast Yellowstone. Eastgate continues to show new pine beetle kill in the badly hit whitebark pine forest with what looks like redkill from pine beetle. There is budworm in this area too, and the white trunks stand out. In 2009, there was a big burn just east of here. The upper left mountain flank in this image shows a little burn scar to compare with the beetle damage. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Warming shifts ecosystems to higher elevations in the mountains. But those ecosystems at higher elevations, like the lodgepole forests, have nowhere to go as warming occurs, and the forests literally disappear. Ultimately, brush, scrub and grasslands will take their place, leaving only the highest altitudes or the wettest areas forested. Even if we halted all fossil fuel greenhouse gas emissions tomorrow morning, there would still be enough warming in the pipeline to push many ecosystems in the West above the elevation of the tops of the mountains where they reside. Abrupt change impacts the most vulnerable ecosystems first. Then, the more robust ecosystems begin to fall. We are entering this second phase of abrupt change now.

In total, there were 3.8 million acres of new impacted forest across the US West in 2013. The spruce beetle attack was a half million acres, up from 317,000 in 2009. The fir engraver beetle, western pine beetle, Douglas fir beetle, ips beetle and subalpine fir mortality complex, in which the trees succumb to multiple infestations and infections simultaneously, impacted about 250,000 acres each, with most of these categories seeing a significant increase since the late 2000s. The total lower 48 footprint of the mountain pine beetle alone, from 2000 to 2014, was 25.1 million acres.

Normal “abrupt” climate change has happened naturally over 20 times in the last 100,000 years. Evidence comes from highly accurate sources that include ice sheet cores, sediment cores and cave formations. It happens every half-dozen millennia, give or take 3,000 or 4,000 years, and is what normally happens when we have “climate change.”

Sadly, the slow, steady warming of a few to several degrees Celsius over a century that climate scientists have been trying to prepare us for is decidedly not the most important way our climate normally changes. Abrupt change averages 9 to 15 degrees Fahrenheit globally, with 25 to 35 degrees Fahrenheit at high altitudes and latitudes and only modest warming at the equator. The changes usually happen in generations, or even decades, or at the most extreme, even a few years in Greenland. As of yet, there is no clear indication of how fast abrupt changes are at high altitude.

Mountain pine beetle at May Creek Campground, Beaverhead/Deer Lodge National Forest Montana. West from Yellowstone into Idaho and Montana, wherever there is forest, there are beetles or budworm: The Lemhi Range, the Beaverkill and the Lost River Range are all impacted to some extent. Several campgrounds have active logging to remove hazard trees. The southern extent of the Lemhi Range is particularly hard hit with redkill from mountain pine beetle. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Mountain pine beetle at May Creek Campground, Beaverhead/Deer Lodge National Forest Montana. West from Yellowstone into Idaho and Montana, wherever there is forest, there are beetles or budworm: The Lemhi Range, the Beaverkill and the Lost River Range are all impacted to some extent. Several campgrounds have active logging to remove hazard trees. The southern extent of the Lemhi Range is particularly hard hit with redkill from mountain pine beetle. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Evidence of past abrupt climate change is widespread in ice cores, ocean sediments, cave formations and corals across the globe. But computer models are only recently, in 2015, beginning to model past abrupt changes. Future projections are not yet possible. Because of this, the climate science consensus has yet to recognize them as a means to direct the creation of policy.

We are undergoing the beginning of a grand reordering of ecological systems. This is more than simply a harbinger of things to come. An extinction bomb has gone off and it will not stop going off until we stabilize our climate.

In Canada, the mountain pine beetle attack is moving into a new phase. While the kill is smaller than what it was in the 2000s, it has now moved into the high latitude boreal forest of the subarctic and jumped species again to the black and jack pine forests of the North – the largest and most sensitive forests on the planet.

Despite the return of normal and even above normal rainfall across the Rockies over the last half-dozen years, beetle kill continues to advance. This is because a little warming creates a lot more evaporation. It is an apparent drought and is driven by the nonlinear relationship between temperature and evaporation. To the trees, it’s the sum of rainfall and evaporation that matters.

Across the Continental Divide 22 Times

In 21 days, our little film expedition made 17 different camps from Santa Fe to Missoula. New significant mountain pine beetle attacks were seen in most forests we visited. Spruce beetle, fir beetle and budworm seemed to be everywhere this trip. The most extreme infestations of spruce beetle were generally at altitude in Colorado and far northern New Mexico, but severe attacks of all beetles and budworm were virtually everywhere there was forest.

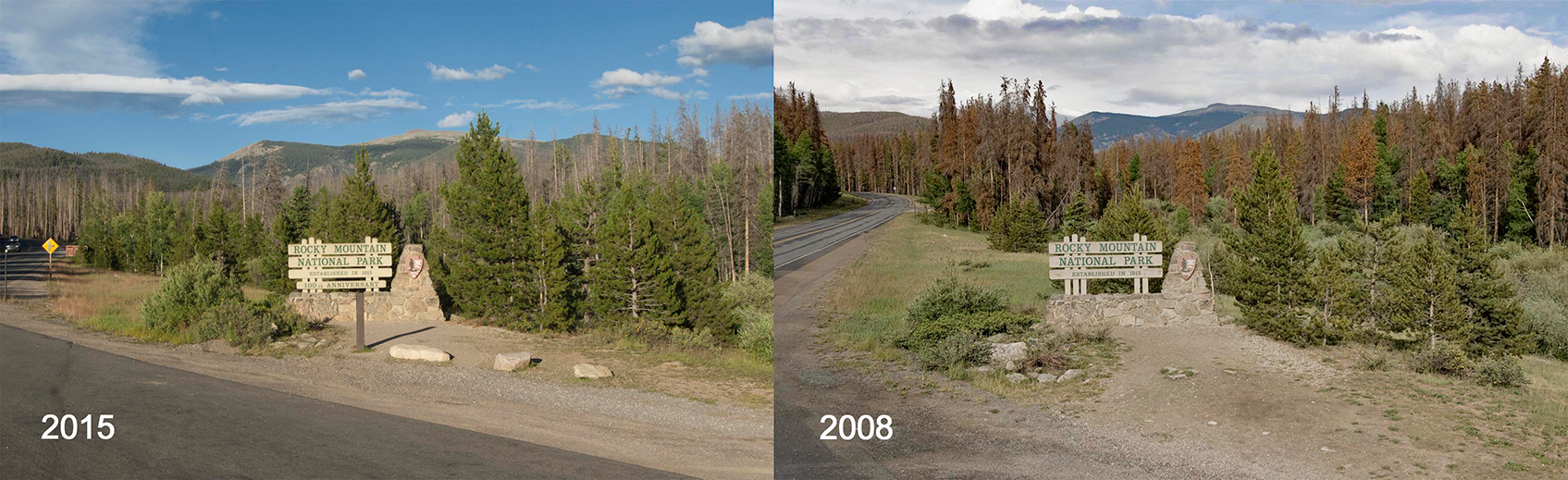

Rocky Mountain National Park Westgate entrance monument comparison (Click here to view larger in a new window). The peak of the redkill in this area was 2008. Note the tall trees between the road and the monument that have been logged to prevent them from falling on the road. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Rocky Mountain National Park Westgate entrance monument comparison (Click here to view larger in a new window). The peak of the redkill in this area was 2008. Note the tall trees between the road and the monument that have been logged to prevent them from falling on the road. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Our course passed through 19 national forests and two national parks. It was cold, it was sunny, it rained, but there was no snow last summer (it does usually snow on us every summer at altitude in the Rockies). We had more than a few campfires and saw mountain range upon mountain range extending day after day in a blur of green, red and brown conifers, little towns, big mountains, camp meals, interstates, gravel roads, sunsets, wildlife, fabulous vistas and, where needles have already dropped, ghost forests of skeleton trees.

Hallmark of Climate Change: Increasing Extremes

This ecosystem collapse is not being caused by the warming per se. It is the increase in extremes that matter. Species evolve with the ability to cope with certain weather extremes. Increase those extremes and unless species can migrate, they don’t do so well. If they don’t die outright, they get sick and mortality increases. Across the American West, annual tree mortality has doubled from 1.5 to 3 percent per year, not counting the pine beetle attacks. When compounded over time, the average age of the forest drops to just a few human generations after 20 to 30 years.

The reverse is true as well. Lodgepole pine relies on 40 below zero temperatures to kill pine beetles. Because extremely low temperatures at night during the winter warm the most with climate change, the beetles win.

The Never Summer Range, just to the west of the northern section of Rocky Mountain National Park. Spruce beetle attack in the Never Summers is heavy above 10,000 feet. Dead lodgepole (foreground left) remain after the mountain pine beetle swept through in 2008. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

The Never Summer Range, just to the west of the northern section of Rocky Mountain National Park. Spruce beetle attack in the Never Summers is heavy above 10,000 feet. Dead lodgepole (foreground left) remain after the mountain pine beetle swept through in 2008. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Warming enhances warming-related extremes nonlinearly. For example, NASA and Columbia researchers have shown that extreme heat that once happened across 0.1 to 0.2 percent of the Northern Hemisphere every year now happens across 10 percent every year. This means we have already experienced – with just a little more than 1 degree Fahrenheit of warming – an increase of heat extremes of 10 to 100 times.

If lodgepole pines had legs, they would migrate to a more hospitable climate. The problem is that most of the life forms on this planet cannot migrate. They are stuck with the ecosystem where they live. As extremes continue to increase disproportionately, risks of ecological catastrophe similarly increase.

A Happy Ending?

We are currently implementing emissions reductions policies that are less stringent than in the early 1990s. The treatment of climate pollution has been delayed for so long, and we have emitted so much more climate pollution, that annual emissions are now only about 4 percent what remains of 200 years worth of accumulation in our sky. Complete cessation of emissions will still result in up to 7.5 degrees Fahrenheit warming because of the great delay of impacts relative to when emissions were made.

The same influences that have masked this beetle pandemic from common knowledge have also masked 20 years of valid climate science findings. Almost all impacts are happening ahead of schedule. For example, Antarctica has begun to lose ice 100 years ahead of projections.

New findings about “net warming” are maybe the most important of all the science that has been obscured and can be summed up by the complicated but simple statement: Killing coal produces more warming than doing nothing.

Net warming considers both global warming and global cooling pollutants, but current policy (all of it) is based only on warming pollutants. The reason that net warming is not considered is we simply have not had the knowledge to understand how global cooling pollutants work until the late 2000s. Scientists have understood global warming pollutants to be a tremendous threat for nearly 30 years, so they suggested we reduce their emissions to minimize the risk. But new science has revealed a new twist.

Now we know that cooling from global cooling smog pollutants emitted from burning coal is actually greater in the short term (20 to 50 years) than the warming produced from carbon dioxide emitted right alongside the smog. After 20 to 50 years the cumulative effect of the cooling smog pollutants maxes out, but because carbon dioxide is so long-lived, their cumulative warming effect continues to increase. This is ever so important because every bit we warm increases the risk of crossing a threshold into an abrupt climate change.

But the most important thing of all is that the same influences that have so badly obscured valid climate science have also masked the ease and economic feasibility of the only climate pollution solution that matters today. This solution is called direct air capture of carbon dioxide. We have done this since World War II and in the early 2000s research began to show new technologies that were vastly less costly than the old ones.

Ponderosa pine on Rock Creek, Lolo National Forest, Montana. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Ponderosa pine on Rock Creek, Lolo National Forest, Montana. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

But a few pieces of well-timed research, one co-authored by a BP executive, which evaluate only the mature World War II technologies, and use the basic physics inaccurately, have so overshadowed the larger body of work that direct air capture is not considered an alternative.

We can still avoid the worst impacts of climate change, but we are not going to do this with current emission reductions policy alone. Everything has a cost, and this will cost trillions. But, to put things in perspective, the United States spent an average of $2 trillion per year on health care from 2000 to 2009.

This attack of a tiny insect needs to be viewed for what it is – the complete destruction of large regional ecosystems. We don’t get these forests back unless we put our planet’s climate back where it was. More destruction like this will come faster in the future as impacts increase nonlinearly. After over 20 years of delay, the urgency is greater than ever that we implement more meaningful climate policy than what is currently being proposed.

Postscript: A detailed narrative of the entire trip, all the camps, forests and mountain ranges, along with a lot more photos, can be seen at ClimateDiscovery.org. See more photos of previous expeditions here.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.