The reeds and grasses are as tall as Sebastián Pérez Méndez, if not taller. The vegetation is so thick it’s hard to see the water in the Suyul Lagoon that he and other local Maya Tzotzil residents are working hard to protect. Pérez Méndez crosses the road to point out where aquatic plants serve as a natural filter for the water as it flows out the lagoon, located in the highlands of Chiapas, in southern Mexico.

“The water is under threat,” he said. Pérez Méndez is the top authority of the Candelaria ejido, a tract of communally-held land in the municipality of San Cristóbal de las Casas. “We’re not going to allow it.”

Communities in Chiapas are organizing to protect the Suyul Lagoon and communal lands from a planned multi-lane highway between the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas and Palenque, where Mayan ruins are a popular tourist destination. Candelaria residents continue to take action locally to protect the lagoon. They also traveled from community to community along the proposed highway route, forming a united movement opposing the project.

It all started back in 2014 when government officials showed up in Candelaria looking for ejido authorities, including Pérez Méndez’ predecessor. It was the first residents had heard about plans for the highway. The indigenous inhabitants had not been consulted and were not shown detailed plans.

“They realized that [the government officials] were only seeking signatures,” Pérez Méndez said.

No one person or group is authorized to make a decision that would affect ejido lands, however, and there are strict conditions in place to ensure elected ejido leaders are accountable to members, he explained. An extraordinary assembly was held to discuss the highway project.

Candelaria residents paint over graffiti to fix up a roadside sign proclaiming their opposition to the highway project. (Photo: WNV / Sandra Cuffe)

Candelaria residents paint over graffiti to fix up a roadside sign proclaiming their opposition to the highway project. (Photo: WNV / Sandra Cuffe)

The Candelaria ejido was established in 1935, a year after a new agrarian law enacted during the Lázaro Cárdenas administration led to widespread land reform throughout Mexico. More than 2,000 people live in the 1,600-hectare ejido, and more than 800 of them are ejidatarios – legally recognized communal land holders whose rights have been passed down for generations. Only ejidatarios as a whole have the power to make decisions on issues like the highway project.

“The ejido said no,” said Guadalupe Moshan, who works for the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, or FrayBa, supporting Candelaria and other communities in Chiapas. “They didn’t sign.”

Candelaria leaders sought assistance from FrayBa in 2014, after they were approached by government officials and pressured to sign a document indicating their consent to the highway project that would involve a 60-meter-wide easement through communally-held lands. Officials told community members that the highway was already approved and that they would be well compensated, but that there would consequences if they refused to sign, Moshan said.

“They told them they would suspend government programs and services,” she explained. In the days following the extraordinary ejido assembly rejecting the project, there was unusual activity in the area, according to Moshan. Helicopters flew over theejido, unknown individuals entered at night, and trees were marked, she said.

Protecting the Suyul Lagoon remains at the heart of Candelaria’s opposition to the planned highway. The lagoon provides potable water not only for Candelaria, but also for several nearby communities, said ejido council secretary Juan Octavio Gómez. Aside from the highway itself, project plans eventually shown to the community leaders include a proposed eco-tourism complex right next to the lagoon. That isn’t in the communities’ interest, Gómez explained.

“Water is life. We can’t live without it,” he said. “Without this lagoon, we don’t have another option for water.”

Fed by a natural spring, the Suyul Lagoon never runs dry. Local residents are careful to protect the water and lands in the ejido, where the majority of residents live from subsistence agriculture, sheep rearing and carpentry. They engage in community reforestation, but have plans to plant more trees, Gómez said.

The Suyul Lagoon is also sacred to local Maya Tzotzil. Ceremonies held every three years in its honor involve rituals, offerings, music and dance.

“It is said that it’s the navel of Mother Earth,” Pérez Méndez said.

Candelaria residents didn’t sit back and relax after rejecting the highway project in their extraordinary assembly. They have been organizing ever since. The Suyul Lagoon lies just outside the Candelaria ejido, but it belongs to ejidatarios by way of an agreement with the supportive land owner. Aside from the highway project and potential eco-tourism complex, the lagoon has caught the attention of companies, whose representatives have turned up in the area expressing interest in establishing a bottling plant.

It’s cold in February up in the highlands, but community members have been out all day, erecting a fence around the Suyul Lagoon to protect it from intruders. White fence posts are visible under the treeline across the sea of reeds. Like so many other local initiatives, fence materials are collectively financed by the ejido and the labor is all voluntary, communal work.

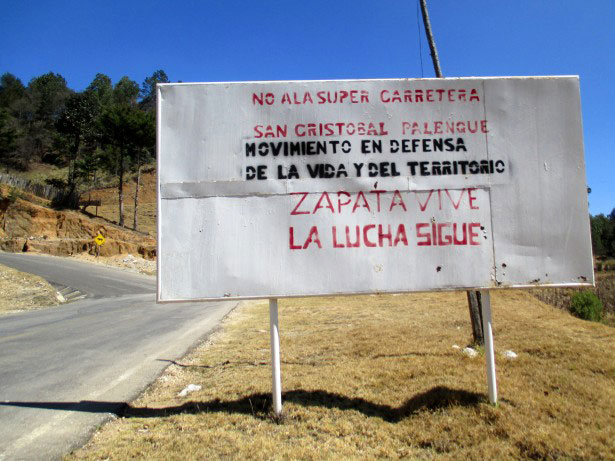

While residents continue stringing barbed wire from post to post, others take paintbrushes to one of their roadside signs. Locals have erected large signs next to roads in and around their ejido, announcing their opposition to the tourist highway.

A sign along the road leading to Candelaria informs passersby of opposition to the planned superhighway. (Photo: WNV / Sandra Cuffe)

A sign along the road leading to Candelaria informs passersby of opposition to the planned superhighway. (Photo: WNV / Sandra Cuffe)

“We’re also already organized with the other communities,” Pérez Méndez said. “All the communities reject the superhighway.”

After they were approached by government officials, Candelaria ejido residents traveled from community to community along the entire planned highway route. Some communities hadn’t heard of the project at all, while others said they were pressured into signing documents indicating their consent, Pérez Méndez said. As a result of Candelaria’s visits, community organizing along the highway route led to the formation of a united front of opposition, the Movement in Defense of Life and Territory.

Candelaria also recently got together with other indigenous communities in the highlands to issue a joint statement rejecting the tourist superhighway and a host of other government and corporate projects and policies.

“Our ancestors, our grandfathers and our grandmothers have always taken care of these blessed lands, and now it’s our turn to [not only take] care of the lands, but also to defend them,” reads the February 10 communiqué.

“The neoliberal capitalist system, in its ambition to exploit natural assets, invades our lands,” the statement continues. “The government and transnational companies are violently imposing their mega-projects.”

Back along the edge of the Suyul Lagoon, Candelaria residents continue to string barbed wire from post to post. They’ve been at it for a while now, according to Pérez Méndez, but they’ve now stepped up their efforts and hope to finish the fence by the end of the month.

Pérez Méndez surveys the progress, protected from the unrelenting sun and icy wind by his hat and white sheep’s wool tunic. He becomes pensive when asked if he thinks communities will be able to defeat the highway project.

“Yes,” the ejido leader said, after giving it some thought. “We can stop it.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.