Part of the Series

Beyond the Sound Bites: Election 2016

Bernie Sanders’ campaign, which proposed replacing the Affordable Care Act (ACA), with a Medicare for All system, has sparked a much-needed debate over the need for a single-payer health system. But this bold proposal didn’t win him the election. And now that Hillary Clinton has become the presumptive nominee against Donald Trump, the debate over health care reform is about to become extremely narrow.

With the media and candidates in full general election mode, Sanders’ argument that we must do better than Obamacare will soon be replaced by Trump’s insistence that we must do worse. Clinton will almost certainly respond by pushing the status quo, which remains broken. Critical dialogue, at least on the national stage, will likely be in short supply.

Obamacare, while responsible for many positive developments, is not a solution to our health care crises.

The Clinton campaign, prompted by Sanders’ strong showing and her relationship with the drug and insurance industries, declared war against single-payer this year. Her allies — establishment economists and so-called “left-leaning” (industry-supported) think tanks — promptly followed her lead. These efforts, as Adam Gaffney explains in the New Republic, were attempts “to kill the dream of single-payer,” a “cherished policy goal of the left.”

Yet, for all the (often dubious) attacks that Clinton loyalists made against Sanders’ proposal, they have placed the existing law under virtually no scrutiny. In fact, Clinton and her supporters have issued bold claims that the ACA renders more reform — and even critical discussion — pointless. “We finally have a path to universal health care,” Clinton said. “And I don’t want us to start over with a contentious debate.”

But does the ACA really achieve these lofty heights? Can it lead to universal health care? The unfortunate reality is that Clinton is wrong. Obamacare, while responsible for many positive developments, is not a solution to our health care crises. The law is hampered by at least three major structural flaws: It does not lead to universal health care; it fails to slow costs enough to make it sustainable; and millions of Americans who do have health insurance are nevertheless left underinsured and exposed to financial ruin.

These limitations are very real, regardless of one’s view on single-payer. The ACA needs to be analyzed on its own merit. Such an analysis shows that the law cannot credibly be sold as a long-term solution or as a path to universal health care. It is important the public has an honest discussion about these realities, even though we cannot expect this discussion to take place within the spectacle that is the 2016 presidential election.

Former Health Administrator: Obamacare Is Progress, Not a Solution

While Clinton doesn’t want a “contentious debate,” the debate among liberals and the left doesn’t have to be so contentious, says Dr. Donald Berwick, former administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, in an interview with Truthout. There is room to appreciate what the law can do, he argues, while also understanding its limits.

“I feel the ACA is a massive step forward — a tremendous achievement. But we are still left with a system that fails to solve many problems,” said Berwick, who is currently president emeritus and senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. “Even with the law, we still have a complex system that is highly expensive to maintain and somewhat captive to the status quo. It lacks teeth to push back on costs.”

“The ACA is a massive step forward. But we are still left with a system that fails to solve many problems.”

Berwick, who is also a clinical professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, comes at the issue from a unique perspective. In 2010-11, as Obama’s recess appointee to head the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, he was in charge of delivering health care to more than 100 million Americans, and helped to implement the ACA during its crucial early stages. He eventually resigned due to heavy opposition from Senate Republicans. Obama has since filled the position with industry executives straight from K Street’s revolving door; Berwick’s successor, Marilyn Tavenner, is now the head lobbyist for the private health insurance industry at America’s Health Insurance Plans.

Berwick speaks proudly about the progress made under the ACA and recognizes it was created in a “difficult political climate” — the same climate that would eventually force him out of the job. Still, its limitations compelled him to run for governor of Massachusetts in 2014 on a campaign fueled by his staunch advocacy of single-payer health care. “On his first day as governor of Massachusetts, Donald Berwick promises to set up a commission tasked with finding a way to bring single payer to the Bay State,” reported Talking Points Memo, describing him as “Obamacare’s Founding CEO.”

He surpassed anyone’s expectations in the primary, perhaps an indicator of Sanders’ strong showing on the national stage. “Note to politicians: Backing ‘Medicare for all’ is looking less and less like electoral poison,” observed Carey Goldberg of Boston’s NPR affiliate, following Berwick’s second place showing in the 2014 primary.

Berwick’s story is instructive. His direct affiliation with the law makes him a proud advocate of what it does well. His experience with the law and health reform more broadly, however, has shown him that it must be replaced with something more ambitious.

What the ACA Does Well

The ACA’s successes cannot be denied. Most notably, the percentage of uninsured Americans has dropped from a peak of 18 percent to a low of just under 12 percent as of the last quarter of 2015, according to Gallup. If you include those on Medicare, that number dips below 10 percent. That leaves more than 30 million people without insurance, down from about 46 million. These numbers would be better if 19 shameful governors hadn’t opted out of a Medicaid expansion, after a ruling by the US Supreme Court. This has led to a “coverage gap” impacting as many as 3 million Americans, according to estimates from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Obamacare did not establish any precedent of universality or a human right to health care.

The law also prohibits the denial of coverage to patients with pre-existing conditions, gives states a chance to create statewide universal plans (as Colorado is attempting to do) and forces large employers to meet minimum standards on 10 “essential health benefits,” including mental health, addiction and maternity care. Finally, the Congressional Budget Office projects the law to modestly slow the rate at which costs grow, though it does not (as some advocates have falsely claimed) lower costs or stop them from rising.

Clearly, the law has helped millions of Americans. But there are millions who it cannot help due to structural limitations on the issues of universality, costs and underinsurance.

The ACA Is Not a Universal Plan

The most important and obvious problem with the ACA is simple: It is not a universal plan. It has never been a universal plan, and there is no language or provisions that change this. While Clinton has made vague statements about building on the law to create universal health care, she doesn’t have a plan for how to make that happen.

This lack of a strategy for achieving universal coverage is not disputed, even among the architects of the law, although it is not unusual for people in politics or the media to imply otherwise. Around 30 million Americans remain uninsured and the most optimistic projections from the Congressional Budget Office — made prior to the Supreme Court’s ruling on Medicaid expansion — indicated that, at best, 93 percent of Americans would be insured in 2019, leaving out more than 22 million people.

Of the 30 million Americans who have no insurance, thousands will die as a result of being uninsured.

But you could hardly blame some people for believing otherwise. Many liberal writers have either wrongly described the ACA as “universal,” or have otherwise oversold what it means for the country. A good example comes from Vox’s Dylan Matthews, who recently wrote a hagiographic ode to the Barack Obama presidency, referring to Obama as a “towering figure in the history of progressivism.” In the article, he cited Obamacare as the most important reason for this, portraying it as some kind of transformative turning point for the country.

“He signed into law a comprehensive national health insurance bill, a goal that had eluded progressive presidents for a century,” writes Matthews. More telling is this description of the legacy of Obamacare (emphasis added): “It established, for the first time in history, that it was the responsibility of the United States government to provide health insurance to nearly all Americans.”

Matthews doesn’t seem to understand how much the word “nearly,” undercuts his argument. His effusive praise could be fitting to describe whoever does end up passing a universal health care system, but that person is not the president right now. Why would it be the government’s responsibility to cover “nearly all” Americans, but not “all” Americans? It makes no sense.

Obama should not be remembered as the savior of the US health system because Obamacare did not establish any precedent of universality or a human right to health care; it merely tweaked the rules of the marketplace and added subsidies to try and help health care become a more accessible and affordable commodity. Like Gatsby’s green light, the “goal that had eluded progressive presidents for a century” eluded Obama and will elude Clinton, should she be elected. It is debatable if universal health care could really be labeled a “goal” of a President Clinton; the Democrats have effectively abandoned the idea of a national health plan entirely, in favor of the “market solutions” in the ACA.

If Matthews wants to know how short “nearly” universal health care is to actual universal care, he should have a conversation with some of the 30 million Americans who have no insurance, thousands of whom, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health, will die as a result of being uninsured. As usual, the consequences fall disproportionately on the poor. According to Forbes, “about 28 percent of poor Americans and 24 percent of near-poor Americans didn’t have coverage, versus 7.5 percent of Americans who weren’t poor.”

Rising Costs: The “Primary Concern” of the Uninsured

The primary goals of the ACA were improving access and affordability. While the law has had success in the former, its progress on affordability has been far less impressive. “Curbing costs is more complicated [than increasing access],” observed the Economist, rightly noting that “American health care is inefficient and wasteful.”

This is an understatement. Compared to other industrialized nations, the United States is off the charts in health care spending. It devotes more than 17 percent of GDP to health spending. The average member nation of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a coalition of 34 wealthy countries with a “shared commitment to market economies,” spends around 11 percent. This amounts to $8,233 per person in the US, more than double the average for OECD countries ($3,268).

“Even though we are covering more people, costs are going way up for those with insurance.”

When the ACA was designed, its advocates hoped they could help control these costs. But the most recent data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services shows the ACA is failing to do this. “The health share of US gross domestic product is projected to rise from 17.4 percent in 2013 to 19.6 percent in 2024,” the report concludes. This means nearly a fifth of the US economy will be devoted to health care spending. The projections are largely the result of trillions in wasteful, administrative costs for private insurers, including $273.6 billion attributable to the ACA.

Private insurance companies transfer this burden to US “consumers,” who are constantly paying higher premiums and co-pays. “One of the things that [is] going on is that we are shifting costs to patients,” Berwick said. “So even though we are covering more people, costs are going way up for those with insurance.”

Premiums went up by 5.4 percent in 2015 and much sharper increases are predicted in 2016 and beyond. On June 1, The Associated Press (AP) reported that the largest insurer in Texas is proposing increasing premiums “by an average of nearly 60 percent, a new sign that President Barack Obama’s overhaul hasn’t solved the problem of price spikes.” The federal government has no power to “roll back the increases,” the AP reports.

Affordability issues often keep Americans from using their insurance, or buying insurance at all. The US Department of Health and Human Services, the chief proponent and administrator of Obamacare, has documented much of this. “Nearly 75 percent of all uninsured people think that having health insurance is important,” concludes its 2016 study on uninsured Americans. These uninsured Americans, it continues, “are primarily concerned with the affordability of coverage.”

Underinsurance Leaves Millions Exposed

Even with the improvements made by the ACA, many Americans who have insurance are still underinsured: They have plans that do not protect them from major financial problems. The Commonwealth Fund estimates 31 million Americans are underinsured, a number that “has doubled since 2003.” Obamacare, which has many high-deductible plans, does not solve this problem. “Rising deductibles — even under Obamacare — are the biggest problem for most people who are considered underinsured,” The Hill reports.

Underinsurance often results in patients forgoing care they need due to the costs they would incur, despite having insurance. Consider that the least expensive plan in Massachusetts (as of May 31) costs a single individual $208 per month, has $6,550 in estimated out-of-pocket costs and has a deductible of $2,500. Even after a patient meets the deductible, one is still on the hook for the following expenses (which represent just a fraction of the out-of-pocket obligations): 35 percent of surgical costs, $1,000 per ambulance ride, $750 for an emergency room visit and $1,000 for inpatient drug treatment.

“For better or worse, we treat health care in the United States as a commodity.”

This burden only ends once a patient meets the maximum out-of-pocket limit ($6,875 per individual, $13,700 for a family). Yet, as the Department of Health and Human Services observes, “nearly eight in ten of all people [eligible for a plan] without insurance have less than $1,000 in savings and about half have less than $100 in savings.” How does someone with less than $100 in the bank pay, for instance, $1,000 for inpatient drug treatment or $750 to visit the ER? Inevitably many simply don’t get the treatment they need.

Subsidies can help cover premiums for those with lower incomes, but for those with bronze plans (the lowest tier of plans with the least expensive premiums), it provides no help on cost-sharing expenses (such as deductibles and co-pays). For cost-sharing subsidies, one must purchase a “silver plan,” with a higher premium. Lower deductibles require costlier premiums, while lower premiums expose one to higher deductibles. When many people can’t afford either, it is a sure sign the health care system is fatally flawed.

These expenses have made medical debt the largest cause of bankruptcies in the US; it results in more collections than credit card debt. A 2013 Commonwealth Fund study shows that 37 percent of Americans have forgone care or failed to fill a prescription due to costs, by far the highest such rate among wealthy nations. “The US has always been an outlier when it comes to costs, access, and affordability. Far too many people go without care or can’t afford to be sick, even when they have health insurance,” said Cathy Schoen, lead author of the study.

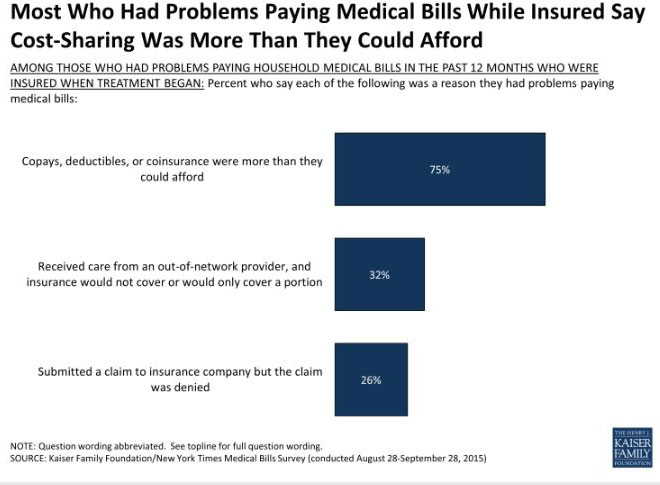

The ACA does not fix this problem, according to a New York Times/Kaiser Family Foundation report, described as “the first detailed study,” on medical debt since the ACA went into effect. The 2016 report concludes that 20 percent of insured adults under 65 have had problems paying their “medical bills.”

(Courtesy of Kaiser Family Foundation)

(Courtesy of Kaiser Family Foundation)

(Courtesy of Kaiser Family Foundation)

(Courtesy of Kaiser Family Foundation)

Health as a Commodity: A Moral Failing

Now that the presidential primary is winding down, the ACA will likely receive very little serious criticism in the dominant media and on debate stages. Republicans will likely scream about the perils of socialized medicine and death panels. The most prominent Democrats will likely tout the law as something it is not: a pathway to universal health care. With Sanders no longer considered viable, his argument that the US must cover every American and rid the system of premiums and co-pays is in danger of fading into the background of the electoral circus. But if we truly want a country where health care is a right for everyone — and not “nearly” everyone — it is important that we are honest about the future of health care in the US under Obamacare.

“For better or worse, we treat health care in the United States as a commodity,” writes Howard Waitzkin of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. “We buy and sell it, and would-be patients who don’t have enough money to buy it must either rely on limited public assistance or go without care. In very real terms, it’s not just health care that we have turned into a commodity, it’s health itself.”

The very idea of health care being sold as a commodity is a moral outrage. Beyond that, it has also proven to be a wasteful, inefficient system that leaves many millions without care. The Affordable Care Act, written with extensive input from the insurance industry that profits off our broken system, failed to change this. For all the fanfare surrounding the ACA, health care is still a product and not a human right. This, as much as anything else, is why the ACA will never lead to a truly just, inclusive, universal health care system.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.