Wednesday, July 27, should have been the day that 27-year-old Shaylene Graves walked out of prison a free woman. After eight years in prison, Graves, known as Light Blue or simply Blue to her friends, was looking forward to her first meal out of prison and the welcome-home party her family was planning.

Her family never got to throw that party. At 6:30 am on June 1, Graves’ mom Sheri was sitting in her car waiting for her oldest son Michael. As they did every weekday morning, the two were planning to drive from their home in Corona to Irvine where Sheri worked as a nurse and Michael as a barber. As she was backing the car out of the driveway, Sheri’s cell phone rang. On the other line was an officer at the California Institution for Women (CIW), the prison where Shaylene was finishing her sentence. He told Sheri that her daughter was dead.

Michael grabbed the phone and asked how his sister had died. “He said, and you can quote me on this, ‘We found her hanging. She hung herself,'” Michael told Truthout.

“You’re saying my sister committed suicide a month before she was getting out of prison?” Michael asked. The voice on the other line paused before adding that Graves had had a cellmate, throwing doubt onto his initial statement that Graves had hung herself. He did not say anything more.

Graves’ death is the latest to rock CIW, which is currently at 135 percent capacity: 1,886 women in a prison designed for 1,398. Overcrowding isn’t new; even before California completed its conversion of Valley State Prison for Women to a men’s prison, transferring approximately 1,000 women to two other prisons, CIW was operating at capacities ranging from 125 to 185 percent.

CIW had one suicide this past April and, as of May 31, nine unsuccessful attempts. Between 2013 and 2015, the prison had 65 suicide attempts and five suicides. CIW’s suicide rate is five times the rate for all other California prisons and eight times the rate for women’s prisons nationwide. In January 2016, Lindsay Hayes, project director at the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives (NCIA), who audited suicide prevention policies at all California prisons in 2013 and re-audited several in 2015, noted that CIW continued to exhibit poor suicide prevention practices.

Even those not prone to suicidal ideation find it difficult to maintain hope at CIW. The overcrowding has led to a widespread inability to access programs, as well as delays and inadequate medical and mental health care. Several women at the prison have stated that the drug trade is thriving — and that even those not involved are negatively impacted.

No one is sure what happened to Shaylene. Since that early morning phone call, her family has been searching for answers — and coming up empty-handed.

“I’m Here for My Sister”

That morning, after the call, Michael took his shocked mother into the house, then he and his younger brother L.G. drove the 15 minutes to CIW to find out what had happened to their older sister.

At the CIW visitors’ entrance, two uniformed officers were standing on the walkway, seemingly in conversation. When they noticed the brothers, Michael said, they placed their hands on their guns. “I put my hands up and said, ‘I’m here for my sister.'” In response, the officers, keeping their hands on their guns, stepped in front of the brothers. Several other guards joined them.

Michael asked if there was surveillance footage of Shaylene’s death. He also asked to see his sister. The answer to both questions was, no. He was told that the death was under investigation and prison officials could not tell him anything. Frustrated, the brothers left.

They came back at noon with their mother, aunt and uncles. This time, the family made it through the front door. They identified themselves and asked to speak with the warden. In response, both Sheri and Michael say, prison staff called the local police. Two officers showed up — one waited outside while the other remained inside the lobby as Sheri asked first to speak with the warden, then for the record of what had happened to her daughter and the prison’s protocol around death in custody. Though CDCR’s operations manual, including its policy for when a person dies in custody, is available online, staff told her that it was an internal policy that could not be shared. No one could tell them when they would be able to retrieve Graves’ belongings. The coroner’s office told Sheri that it would mail her a report in six to eight months.

According to Rosie Thomas, the prison’s public information officer, CDCR is investigating Graves’ death and cannot disclose information about the circumstances. When asked about interactions between Graves’ family and prison staff that morning, she wrote in an email that “such information cannot be disclosed to protect the integrity of the investigation” and would only confirm that personnel in a position of authority spoke with family members. According to several women at CIW, Graves’ cellmate was initially sent to suicide watch and then to administrative segregation, a form of isolation, as the investigation continues.

“She Always Had a Smile on Her Face”

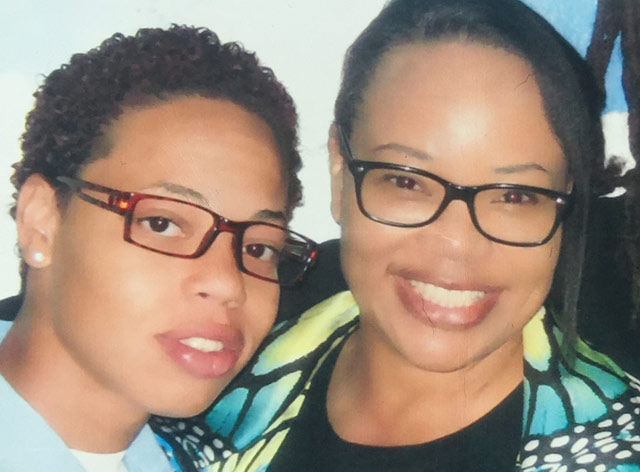

17-year-old Shaylene Graves travels to Sacramento to watch a state championship basketball game. (Photo: Sheri Graves)Janelle Chambers met Graves in 2008 while incarcerated at the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) in Chowchilla. Three years later, the two became roommates. Though they shared a cell with six other women, the two connected and quickly became good friends. “She always had a smile on her face,” Chambers told Truthout. “You could be having the crappiest day, but as soon as you saw Blue, you felt better.” As she walked through the prison, Graves greeted each person she passed. “She’d make you wanna come out of being mad. Her smile — and her saying ‘What’s up? How you doing?’ — instantly made you feel her energy, her good vibe.”

17-year-old Shaylene Graves travels to Sacramento to watch a state championship basketball game. (Photo: Sheri Graves)Janelle Chambers met Graves in 2008 while incarcerated at the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) in Chowchilla. Three years later, the two became roommates. Though they shared a cell with six other women, the two connected and quickly became good friends. “She always had a smile on her face,” Chambers told Truthout. “You could be having the crappiest day, but as soon as you saw Blue, you felt better.” As she walked through the prison, Graves greeted each person she passed. “She’d make you wanna come out of being mad. Her smile — and her saying ‘What’s up? How you doing?’ — instantly made you feel her energy, her good vibe.”

Mianta McKnight agrees. McKnight, who spent 18 years and one day in prison, still remembers her first day at CCWF’s auto body detailing program. “I wanted to know everything,” she told Truthout. Graves, who was also a student, took the time to explain each tool and make sure that McKnight understood how to use it. She remembers Graves singing along to the music played in their classroom — and that she always brought a snack to share. “She was a happy person,” she recalled.

Chambers was paroled in 2012. The night before her release date, she, Graves and a third roommate pulled their mattresses off their bunk bed frames and placed them on the floor for a sleepover. “We listened to music all night, we talked, laughed, had pillow fights,” she recalled. The next morning, the two women walked Chambers as far as they could. Though she was ecstatic to leave prison, Chambers was sad to leave Graves. “We kept hugging while they [prison staff] repeatedly called my name over the loudspeaker,” Chambers said. “I heard someone say, ‘Who the heck is late to parole?'” Thinking back on that morning, Chambers said, “Somebody who had a friend like Blue. I didn’t want to leave her in that ugliness.”

Chambers and Graves stayed in contact for the next four years, writing letters and talking on the phone three to four times a week. As Graves’ release date drew closer, they began making plans. “We talked about all the food she was going to eat,” remembered Chambers, who lives near a casino and planned to bring Graves there. “She had never been anywhere where she could order a mixed drink,” she said, noting that Graves was 19 years old when arrested.

“There’s Nothing Like This at Chowchilla”

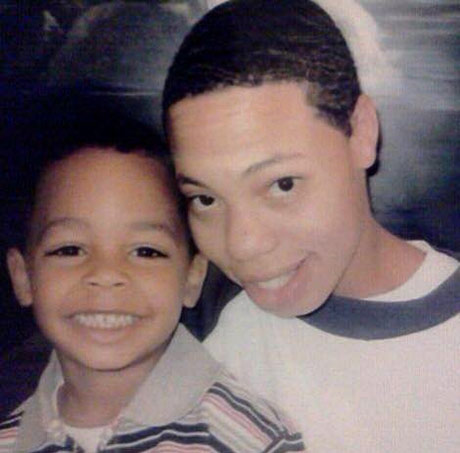

Shaylene Graves’ son visits her at the women’s prison in Chowchilla in 2012. (Photo: Sheri Graves)In April 2015, Graves was transferred from Chowchilla to CIW to be closer to her family, particularly her 76- and 77-year-old grandparents for whom the 300-mile drive was becoming more difficult. “It was much easier for us to visit,” Sheri told Truthout. “We had no idea of the conditions of the place.” But once Graves arrived at CIW, she began describing the prison’s overcrowding and associated high levels of drug use and mental health problems, during her near-daily phone calls. Though she only had one roommate, rather than seven, she described the prison as “out of control.”

Shaylene Graves’ son visits her at the women’s prison in Chowchilla in 2012. (Photo: Sheri Graves)In April 2015, Graves was transferred from Chowchilla to CIW to be closer to her family, particularly her 76- and 77-year-old grandparents for whom the 300-mile drive was becoming more difficult. “It was much easier for us to visit,” Sheri told Truthout. “We had no idea of the conditions of the place.” But once Graves arrived at CIW, she began describing the prison’s overcrowding and associated high levels of drug use and mental health problems, during her near-daily phone calls. Though she only had one roommate, rather than seven, she described the prison as “out of control.”

“There’s so much drugs here,” she told her mother more than once. “There’s nothing like this in Chowchilla.”

Chambers, who had never spent time at CIW, said that Graves described the prison as “drug-infested” with people owing debts for drugs and “so many zombie-like people, people getting ready for the next hit, fighting all the time because of the [drug] debts.”

Between May 2015 and May 2016, CIW had 48 incidents involving a controlled substance. By comparison, CCWF, which is at 140 percent capacity with 2,803 women, had 29. At CIW, 31 of the incidents involved methamphetamine; CCWF had less than half that number.

“Jackie,” currently incarcerated at CIW, blames the overcrowding for what she calls “an extreme increase in the internal drug trade in the prison system and all the associated fights, lockdowns and increased restrictions.” Writing from prison, she stated, “It is a generally impossible environment to survive in, much less access any real rehabilitation.” In another letter, she noted that a prison administrator told her that CIW had 11 suicide attempts in October 2015 alone. (CDCR records put the number at 12.) “The internal drug trade is alive and well and no one seems to be able to stop it. That is, in my opinion, where most of the suicide attempts come from — unpaid drug debts, hopelessness and oppression.”

Despite the environment, however, Graves remained hopeful. According to her mother, she was participating in a women’s empowerment program. Seeing the number of women whose low self-esteem plummeted even further while in prison, she began making plans for Out of the Blue, an organization to help people upon their release. “Within the last month or two, she was really gung-ho about it,” Sheri recalled, remembering the numerous times that she had had to hand the phone to her boyfriend, an accountant, to answer Graves’ questions about starting a nonprofit organization.

While she never said anything to her family, in the days before her death, Graves told Chambers that she was having problems with her new roommate. “She’s always trying to fight,” Chambers recalled Graves telling her. But staff refused to move either woman.

According to Colby Lenz, a volunteer legal advocate with the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP),others incarcerated at CIW have confirmed that Graves had repeatedly begged prison staff to be moved out of her cell, a practice known as a “bed move.” Staff ignored her requests.

This is not the first time that women’s complaints about cellmates have been ignored. In a January 2016 letter, “Misty” described approaching an officer and requesting that her new cellmate, who had stuck her with a hypodermic needle, be moved. “She had physically overstepped my boundaries and would not move out when I asked her to,” Misty explained. Instead of moving Misty or her cellmate, the officer told two other women, one of whom was actively using drugs, that Misty had informed him that her cellmate had drugs in their cell, thus identifying her as a snitch. The women told others in the housing unit, some of whom, says Misty, were also involved in drug use and distribution. “I’m being faced with theft, violence and made-up stories to feed to the police so that I cannot get any assistance,” Misty wrote.

In April 2016, Kathy Auclair, who lived in the same housing unit as Graves, attempted to commit suicide. Like Graves, she had repeatedly asked for a bed move. Despite having a seizure disorder, she had been assigned to an upper bunk. In addition, her locker in the cell was broken and her belongings, including photos of and letters from her children, had already been stolen once. Afraid of losing even more, Auclair could not sleep. In January, she began experiencing throbbing headaches and intense pain in her neck, spine and throat. By March, even breathing was painful. But medical staff dismissed her symptoms as merely a cold. As the pain worsened and her requests for a bed move were ignored, Auclair gave up and tried to hang herself in the shower. Another woman found her, loosened the noose and called for help.

Auclair was taken to an outside hospital. There, she was diagnosed with valley fever, an air-borne fungal infection that, if left untreated, can cause severe pneumonia, ruptured lung nodules and meningitis. When she was returned to the prison, she was placed on suicide watch, then medical isolation. She was allowed the hospital-prescribed medications but not the supplemental nutritional drink the doctors ordered because of her valley fever-induced weight loss. Auclair lost 18 pounds in two weeks until, with the help of the CCWP, she was able to access the supplement.

On Friday, July 8, within hours of each other, two women, both in the same unit as Graves, attempted suicide. According to reports made to the CCWP, the first was taken to the hospital in an ambulance; the second was sent to suicide watch.

On June 30, instead of making plans to welcome her home, Graves’ family and friends gathered for her funeral. They still don’t know what happened, but they want answers.

“The prison system failed to protect her life,” Sheri wrote two days after her daughter’s death. “She had to forfeit her right to freedom in order to pay her debt to society, but wasn’t supposed to lose her right to life and protection while incarcerated.”

“CDCR needs to be held accountable,” said McKnight, who is now an advocate with Justice Now, an Oakland organization working with people in California’s women’s prisons. “We’re held accountable for the wrong that we do — both in society and inside the prison. That should apply to CDCR too. Just because they’re bigger doesn’t mean they’re better.”

What would this accountability look like? “It would be no more suicides,” stated McKnight. “It would be people taken care of humanely instead of being ignored and treated like animals.” But ideally, reflects McKnight, who was arrested at age 17 and incarcerated until she was 35, “it would be a world with no prisons. People aren’t meant to be locked in cages.”

Graves’ brother Michael agrees. “Why are women being put in prison and being treated like animals? Where’d it all come from? That’s the main thing.”

The Graves family is still grieving, but they’re determined to keep fighting for answers — and for change. They may be facing an uphill battle. “There’s a pattern of CIW and CDCR withholding information from family members grieving their loved ones and seeking answers,” stated Lenz, who has worked with several families whose loved ones have died in prison. “Family members have faced disrespect and mistreatment. Prison officials are generally discouraging if family members ask for medical records and other documentation. A lot of families have given up and don’t believe they’ll ever get answers.”

But Graves’ family has vowed not to give up. “I’m not stopping until no family has to put up with what we went through,” said Michael. “I loved her that much and that makes it easy for me to continue to fight, even if I’m in pain.”

February 2022 Update: In 2022, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation agreed to pay a $3.5 million settlement to the family of Shaylene Graves following the airing of evidence that corrections officers failed to respond to clear signs that Graves’s cellmate was publicly threatening her life. According to ABC7, Attorney James DeSimone said corrections officers also “failed to respond for at least four hours to an escalating argument and loud banging sounds … the night she was killed.” As part of the settlement, her mother Sheri Graves will be allowed to make a presentation to CDCR about her concerns about Graves’s treatment while in prison and what could have been done to save her life.

Shaylene Graves, 17, walks on Monterey Beach during a family vacation. (Photo: Sheri Graves)

Shaylene Graves, 17, walks on Monterey Beach during a family vacation. (Photo: Sheri Graves)

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.