To Kwa Wan is one of Hong Kong’s poorest districts. There’s little resemblance to the shine and glamour of the central shopping district with its imported brands and boutiques. Here, the cheap plastics and household appliances crammed into little shops echo the way people squeeze into tiny, claustrophobic apartments.

It’s also a district marked for urban redevelopment. A new train line is under construction, guaranteed to push up already-staggering property prices the moment it’s opened.

On a fairly unremarkable street, in a space known enigmatically as the House of Stories, the volunteer group Fixing HK is getting ready for another night of repair and outreach.

Max Leung, the group’s spokesperson, summed up their mission by saying, “We volunteer to fix their homes, but we also want to fix their hearts!”

It’s very straightforward: Volunteers of Fixing HK provide repair services to needy members of the community, doing everything from domestic DIY jobs to fixing mobile phones and computers. They then use the access this repair work gives them to serve up a generous side dish of political education.

The group was set up after the headline-grabbing 2014 Umbrella Movement, where protesters camped out at major city intersections from September to December demanding electoral freedoms like universal suffrage.

The protests drew plenty of attention to Hong Kong’s pro-democracy struggle, but also drove deep divisions in society. People’s positions began to harden, making dialogue more and more difficult. Family members found themselves on different sides. Activists setting up street booths found themselves preaching to the converted, while those who disagreed with their stance were sometimes outright hostile.

“The media you consumed determined your position,” Leung said. “We needed to break out of that echo chamber.”

A small group of people camping out by the Legislative Council building in Admiralty decided that work had to be done not just in the sites of sit-ins, but within communities. Among them were workmen and community organizers, so they decided to marry their skills to create an initiative that would open up opportunities to push their cause while also meeting an immediate need.

The group has also bridged divides among the protest movement. While leftists often work on social justice issues like land rights and labor, separatists tend to focus on the political system, demanding complete independence from China. However, since Fixing HK’s focus is on political education and awareness, both of these groups are able to participate.

Largely organized over WhatsApp, Fixing HK now meets every Wednesday in To Kwa Wan’s House of Stories. Although there are about 70 people in the chat group, about 20 volunteers show up at each meeting, according to their schedules and commitments. Early efforts required plenty of cold calls, knocking on doors to explain their service to the district’s residents. Now, they’re well-established enough for people to contact them instead.

“The number [of clients] has shot up,” Leung said. “Now we do about six or seven cases each night, 40 to 50 a month.”

They go out in teams, with a workman (or two) at the core, accompanied by other volunteers — often students, social workers or activists.

“The workmen buy us time to start a conversation,” Leung explained. “You’re together for an hour, and it can be kind of awkward otherwise, so it’s easy to start talking.”

The issues that concerned the Umbrella Movement protesters continue to fester. There’s a lack of democracy when it comes to choosing the head of government; instead of putting it to the popular vote, the chief executive of Hong Kong is elected by a pro-Beijing, pro-business Election Committee. Capitalist interests mean that gentrification carries on apace throughout the city, pushing the cost of living up.

Fixing HK’s goal, then, is to connect the everyday concerns of the people they meet to the broader political struggle. Working in a poor district like To Kwa Wan, the volunteers often encounter people living in subdivided units, flimsy pieces of plywood carving out personal spaces in an already tiny flat.

“We talk to them about their lifestyle and what they care about,” Leung said. “We ask about their rent and it’s often very expensive. We can then point out that there isn’t enough public housing because the government is influenced by big tycoons, and it’s a problem in the system.”

Catherine Ip poses in the small flat she’s lived in for decades. (Photo: WNV / Kirsten Han)

Catherine Ip poses in the small flat she’s lived in for decades. (Photo: WNV / Kirsten Han)

Catherine Ip is 60 years old, but doesn’t look it. It’s the second time she’s reached out to Fixing HK — she needed a power socket fixed, and some racks put up in her kitchen. She’s lived in her flat for about 40 years — maybe 50 she muses, before shrugging — and her accumulated belongings are piled in the narrow hallway so that visitors can only enter single file.

The main repairman for this case is Brother Leung, an electrician whose Umbrella Movement experience involved building roadblocks in Mongkok and clashing with police. He switched off the power at the mains before carrying out his work, plunging the flat into darkness. Without the whirring of the fans, it immediately became oppressively hot.

Ip chattered away as Brother Leung and his assistant, Ah Yin, worked. She’s a diabetic who has battled depression; photos of herself at dance classes — everything from jazz to burlesque — line the doors of glass cabinets so she remembers that happiness is possible.

She pointed out the large cracks in her ceiling, bits of plaster having fallen off to reveal the rough concrete. It’s a job beyond Fixing HK’s ability, and Ip said she can’t get anyone else to do the repairs — other workmen have been turned off by the need to work around the clutter of her flat.

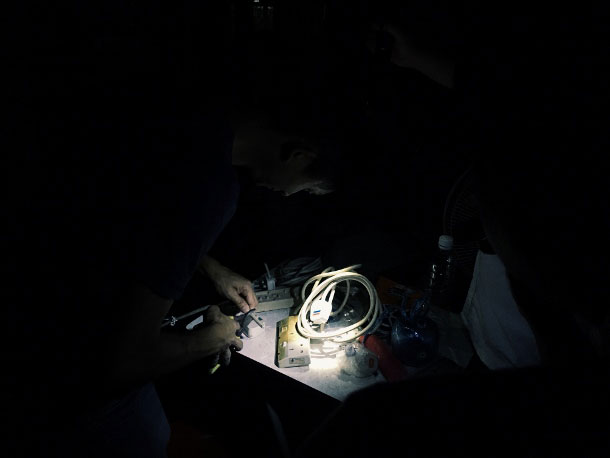

Brother Leung fixes a power plug in the dark while Ah Yin and Catherine Ip hold up small flashlights. (Photo: WNV / Kirsten Han)

Brother Leung fixes a power plug in the dark while Ah Yin and Catherine Ip hold up small flashlights. (Photo: WNV / Kirsten Han)

The talk turned to politics as Brother Leung and Ah Yin got out the power drill to put up the racks. Standing in the crowded hallway, Ip spoke about the To Kwa Wan District Councilor Starry Lee, the chairwoman of the pro-Beijing Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong. Although Ip had previously supported Lee, there’s now a sense that the councilor has become disconnected from the community she claims to represent.

Leung left to head back to the House of Stories, where another client was looking to pick up a refrigerator, but Brother Leung and Ah Yin stayed to finish their tasks.

As far as activism goes, it’s a fairly soft approach. There is no instant call to action, only a slow dialogue prompting reflection and, hopefully, an eventual change in mindset. Doing this week after week requires not just commitment, but also a firm belief that things are changing, even if the result is not immediately visible.

“The workmen are amazing,” Leung said. “They’re like freelancers — they only get money when they work. So every night they choose to come to do this, they’re actually not earning.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $24,000 by the end of today. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.