While the world watched the Olympics, and reporters echoed Donald Trump’s latest absurdities, Black and Indigenous freedom fighters were holding space in revolutionary ways, and their struggles continue.

On the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota, Natives have been encamped for 146 days, in an ongoing effort to thwart construction of the Dakota Access pipeline. In Chicago, Black organizers with the #LetUsBreathe collective have created a living, breathing community space in the shadow of the infamous Homan Square police compound — a facility that some call a “black site,” where people have been held for days on end without being able to contact loved ones or an attorney and where some have been tortured.

The camps in Standing Rock territory have brought my own people — Native people — together in a collective struggle beyond anything I’ve witnessed in my lifetime. With a full spectrum of our people in attendance, from elders who held Wounded Knee in 1973 to young families who’ve come with their children and pets in tow, our peoples have come together to thwart the construction of a 1,172-mile oil pipeline that would imperil the Standing Rock Sioux’s drinking water and disturb sacred and cultural sites. Like many Natives around the country who are using up their vacation days and scraping together gas money to join this historic stand, I spent a few days in Standing Rock recently. It was overwhelming to not only see so many of my people, from so many walks of life, gathered together in common cause, but to also see so many faces from Native justice movements around the country. One after another, I would see old friends and co-strugglers, arriving and contributing whatever skills they could to strengthen the camps.

“We’ve been taught by the Oceti Sakowin Council here that this kind of gathering of the Seven Council Fires hasn’t happened since the Battle of Little Big Horn, when the Lakota banded together to beat down General Custer,” Miwok protester Desiree Kane told me in an interview.

With entire families and tribal elders gathered in prayerful camps now populated by over 2,000 demonstrators, some have expressed shock that the state has pulled out previously provisioned drinking water for the protesters. For those on the ground, the news was troubling, but unsurprising. “No one here is surprised the State pulled out clean water for the camp,” said Kane. “This is all just a 2.0 version of the oldest fight on the continent.”

In Chicago, where I returned home after my journey to the frontlines of #NoDAPL, the #LetUsBreathe collective has been maintaining its Freedom Square encampment for 34 days. Staffed by volunteers, Freedom Square provides free books, free meals and a wide variety of educational workshops and cultural programming in the over-policed, financially neglected community of North Lawndale. Originally formed in concert with a blockade organized by the Black Youth Project 100, Freedom Square is a testament to the kind of investments #LetUsBreathe organizers say the City of Chicago should be making in Black communities — rather than spending four million dollars a day on Chicago’s infamously violent police department.

As neighborhood children flocked to Freedom Square to partake in community meals and enjoy dance lessons and other workshops provided at the site, it became a place where self-determination, love and abolitionist ideology meet the struggle of real world expression. Instead of simply denouncing the police, #LetUsBreathe organizers have committed themselves to an exploration of what building safety and community looks like, without involving the state, while also endeavoring to improve the lives of those living in the community. With concrete demands around police brutality, a highly successful school supply drive for neighborhood youth, and ongoing cultural programming, Freedom Square is a celebration of Black life, Black love and Black resistance.

Native protesters Dean Dedman and Remy show their support for #FreedomSquare from the frontlines of #NoDAPL. Dedman has played a key role in documenting the #NoDAPL protests, while Remy, an arts trainer with The Indian Problem, has helped produce art on the front lines. (Photo: Desiree Kane)

Native protesters Dean Dedman and Remy show their support for #FreedomSquare from the frontlines of #NoDAPL. Dedman has played a key role in documenting the #NoDAPL protests, while Remy, an arts trainer with The Indian Problem, has helped produce art on the front lines. (Photo: Desiree Kane)

Freedom Square has made a priority of improving the lives of Black people living in an oppressed community, but the occupation is clearly more than a neighborhood-based project. It is a direct action that models human potential in a moment of significant social unrest — an aim that many of Chicago’s Black Lives Matter protests have aspired to.

While many Black Chicago organizers are focused on defending the lives of their own people, expressions of solidarity and intersectional analysis have repeatedly emerged in the city’s protest scene. Last month, the grassroots group Assata’s Daughters devoted a section of a rally about anti-Black police violence to Indigenous issues, and the connectivity between state violence against Native peoples and Black people.

Chicago’s Black organizers are aware that Natives are likewise struggling, both with police violence and threats to their life-giving water supplies. “The fight to prevent the pipeline from encroaching on Native land illustrates the ways in which the horrible legacy of genocide against our Indigenous family continues to be resisted,” Black Lives Matter Chicago organizer, Aislinn Pulley explained in an interview. “Like the fight for Black lives, the fight for Indigenous rights reflects a struggle for self-determination,” says Pulley. “The foundation of American empire required the erasure of both Indigenous and Black humanity. These fights for liberation are intrinsically linked, and [that] is why we continue to stand in unflinching solidarity with our Indigenous family.”

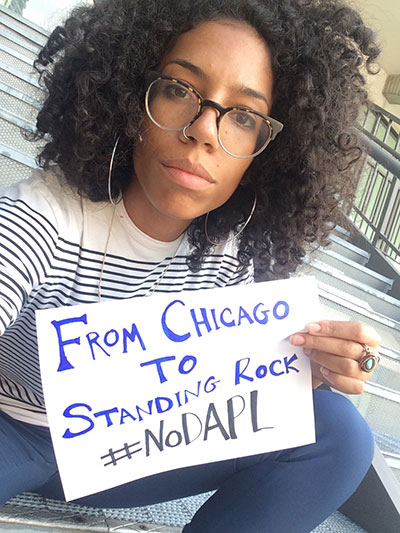

Atena Danner, a Chicago organizer with the Lifted Voices direct action collective, shows support for #NoDAPL on social media. (Photo: Courtesy of Atena Danner)In North Dakota, the connectivity of these struggles is also on the minds of some of those resisting the pipeline. Kwavol Hi’osik is a 34-year-old Akimel O’otham #NoDAPL protester who organizes with the South Mountain Freeway Resistance in her native Arizona. Having travelled to the frontlines of #NoDAPL to join this collective moment of Native resistance, Hi’osik reflected on the connections between Native and Black struggle.

Atena Danner, a Chicago organizer with the Lifted Voices direct action collective, shows support for #NoDAPL on social media. (Photo: Courtesy of Atena Danner)In North Dakota, the connectivity of these struggles is also on the minds of some of those resisting the pipeline. Kwavol Hi’osik is a 34-year-old Akimel O’otham #NoDAPL protester who organizes with the South Mountain Freeway Resistance in her native Arizona. Having travelled to the frontlines of #NoDAPL to join this collective moment of Native resistance, Hi’osik reflected on the connections between Native and Black struggle.

“These kinds of situations are always placed onto communities of color. Understanding the lack of food systems, environmental racism, all of these are connecting issues,” Hi’osik told me in an interview. Seeing the leadership of women and femmes as a common element in Black and Brown struggles, Hi’osik noted, “As women, we organize ourselves daily between our communities and households. So, it’s not uncommon for the women to offer solutions and to be doing the work.”

Speaking to the uniqueness of the historical moment, when two encampments are slowly forcing an awareness of Black and Indigenous issues, Hi’osik suggested that both Black and Native movements are experiencing a different kind of propulsion in the age of social media. “We have instant connection at our fingertips and young people are using these tools in the war.”

Hi’osik also sees connectivity in the spirituality of Black and Brown strugglers and organizers. “One connecting issue is the strong and heavy presence of spirituality and community,” she said. “That is the basis of all of our struggles and the thing that unites us.”

Cody Hall, a Cheyenne River Sioux organizer and spokesperson for the Red Warrior Camp at Standing Rock had these words to offer to the organizers who are maintaining Chicago’s Freedom Square: “Please, stand your ground and speak with your spirit, and never let the oppressors take the narrative from you, because peace is power.”

Encampment, as a protest tactic, has deep historic roots. It means merging the freedom dreams of an oppressed people with the gritty, on-the-ground realities of holding space — often in harsh conditions. Both encampments have held fast in the face of storms and excessive heat and both face possible, if not probable, state reprisal in the coming days. But as #LetUsBreathe organizer Kristiana Colón recently wrote, “Liberation is not some distant utopian goalpost where a journey of political struggle concludes.”

Liberation, as both Black and Native strugglers are reminding us in real time, is the work of living our resistance and our freedom dreams as we create manifestations of both in the world.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.