Part of the Series

Beyond the Sound Bites: Election 2016

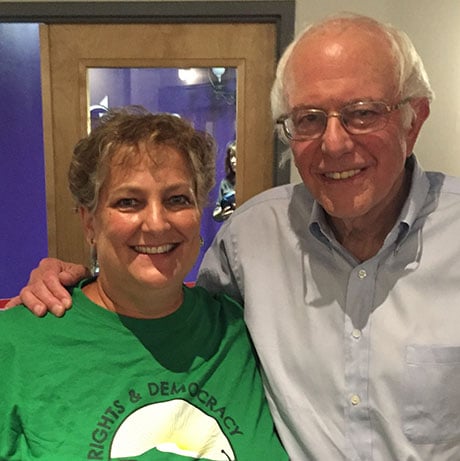

Vermont political candidate Mari Cordes stands with Bernie Sanders. “I have known and worked with Mari Cordes for many years,” Sanders has said. “She is exactly the type of change maker we need in the State House.” (Photo: Courtesy of Mari Cordes)When Our Revolution — the new organization founded by Sen. Bernie Sanders — kicked off in Burlington, Vermont, a nurse and long-time union organizer, Mari Cordes, introduced the iconic senator in front of the many thousands watching across the country. While Cordes is a major advocate for social change in Vermont, she is not a national figure. But some might call her a pioneer whose story may be the epitome of the kind of “political revolution” that Sanders says is “just getting started.”

Vermont political candidate Mari Cordes stands with Bernie Sanders. “I have known and worked with Mari Cordes for many years,” Sanders has said. “She is exactly the type of change maker we need in the State House.” (Photo: Courtesy of Mari Cordes)When Our Revolution — the new organization founded by Sen. Bernie Sanders — kicked off in Burlington, Vermont, a nurse and long-time union organizer, Mari Cordes, introduced the iconic senator in front of the many thousands watching across the country. While Cordes is a major advocate for social change in Vermont, she is not a national figure. But some might call her a pioneer whose story may be the epitome of the kind of “political revolution” that Sanders says is “just getting started.”

Cordes is among several Vermont progressives, many of whom have worked with Sanders in the past, who have already had success in winning down-ticket primaries this year against what Cordes described in an interview with Truthout as “the Democratic establishment in Vermont.” She was endorsed personally by Bernie Sanders in her successful primary challenge for a seat in Vermont’s House of Representatives, against an incumbent Democrat. Since then, she has been among the first candidates endorsed by Our Revolution. She was also endorsed by Rights and Democracy (RAD), a Vermont-based group she helped found, which has similar goals as Our Revolution, emphasizing down-ticket races at the local level.

Cordes is a nurse with a passion for social justice (she was an anti-war tax resister for many years) who ran for local office and won against the political establishment. Her story is a test case in what Our Revolution hopes to accomplish in spades in the coming years. The goal of the “down-ticket strategy” is to transform the Democratic Party by replacing timid, establishment incumbents with passionate progressives who share Sanders’ vision for a world where no one starves, or goes without housing or health care.

There is no doubt that beating out establishment Democrats in elections across the country would be major progress. But can Our Revolution lead to our revolution? Some on the left are skeptical. They question the emphasis on down-ticket races within the Democratic Party as a viable path to revolutionary change and worry the group will be too compromised by the party from the start. Indeed, most Black Lives Matters (BLM) chapters and Occupy in years past, largely refrained from endorsing any political candidates for any office.

There are many unknowns about what electoral activism in the post-Bernie world may look like. What we know for sure is that the Sanders’ message of democratic socialism caught on with much of the public and has prompted millions of Americans — especially young people — to become engaged in the world around them. This has created a major opportunity to mobilize for a better world. And it is an opportunity that would be tragic to squander.

Our Revolution and the Down-Ticket Strategy

“Those who know me well, they know that it is not my personality to look backward … I prefer to look forward,” said Bernie Sanders at the launch of the new organization that aims to continue the goals of his political campaign, which had just ended. “But I do think it is important to say a few words about what we accomplished together.”

Sanders, who reminded his audience that real change always comes “from the bottom up,” listed a number of statistics that, despite being well known to his supporters, still manage to inspire awe: the campaign won 13 million votes, 22 states, 1900 pledged delegates (46 percent of the total) and the “overwhelming support” of young people of all demographics. “When you capture the young people of this country, it means that our ideas, our vision, is the future of this country,” Sanders said.

It is significant that young people, in particular, have adopted a vision that embraces human dignity and resists the corporate greed that dominates politics in the United States. It suggests there is reason for hope in an unjust world, and that people hoping for large-scale change needn’t feel isolated — they know there are millions who share their hope, their fears and even their anger.

However, the election will be over in just a few weeks. What happens then? Sanders will go back to his seat as a senator — one with far more influence than he had when he first joined the Senate 10 years ago. But from the ashes of his campaign, he launched (but will not run) “Our Revolution,” a group that hopes to maintain this grassroots support and push into down-ticket elections across the country. Our Revolution’s website lays out its mission: “Through supporting a new generation of progressive leaders, empowering millions to fight for progressive change and elevating the political consciousness, Our Revolution will transform American politics to make our political and economic systems once again responsive to the needs of working families.”

A “Lot to Prove”: Controversies and Critiques

The launch of Our Revolution was not without controversy. Most notable was the fact that a large portion of the group’s staff quit the organization just as it began, citing problems with Jeff Weaver, the long-time Sanders staffer who helped run his campaign. The departing staffers questioned Weaver’s vision and judgment and frowned on the group’s tax status as a 501(c)(4), which they argued could result in dark money — untraceable donations — being used by the group.

“Jeff [Weaver] has gone on the record admitting that he wanted to form the organization as a 501(c)(4) for the express purpose of accepting billionaire money,” said Claire Sandberg, one of the staff members who quit, in an interview with Democracy Now!

Groups designated as 501(c)(4) can’t have political activity as their primary purpose and are not obligated to share donor information. Robert Maguire of the Center for Responsive Politics (CPR), however, told Truthout in an interview, the term “‘primary purpose’ is not clearly defined.” Maguire also said the staff’s reservations about the status was “a little hard to understand.”

“There is nothing inherently wrong about starting a 501(c)(4),” said Maguire. “There are thousands and thousands of these groups, but the ones we are concerned with are ones without any grassroots support [that] serve exclusively as front groups for political campaigns.”

But these ethics are not the only issue. Sandberg, who was Sanders’ digital organizing director during the campaign, argues that this designation was a strategic blunder that prohibited the group from coordinating with campaigns. She recently approvingly retweeted a link to an Atlantic article which argued that the “political revolution” had failed Tim Canova. The Florida Democrat was endorsed by Sanders over Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, the former head of the DNC who had to resign when it was revealed she was trying to sabotage Sanders’ campaign in leaked e-mails. She is considered by many Sanders supporters to epitomize the Democratic establishment — and she easily beat Canova in August.

“I would absolutely say the prohibition on coordinating hurt the Canova campaign,” Paul Schaffer, the former data and analytics director for Our Revolution, said to the Atlantic.

The kerfuffle made headlines and put the new organization under close scrutiny. “Turmoil is, of course, not foreign to the internal dynamics of movements, but it always needs to be honestly interrogated for the truths it encompasses. Our Revolution, off to a bit of a rocky start, will have a lot to prove,” wrote James Schaffer in Nonprofit Quarterly.

To be sure, the debate over how best to harness the energy from Sanders’ campaign is an important one among the left. And Our Revolution’s strategy of emphasizing down-ticket campaigns and working within the Democratic Party has its detractors.

“Sanders’ strategy of transforming the Democrats will not succeed,” said Ashley Smith, a frequent contributor to the Socialist Worker, in an interview with Truthout. “This is not a new strategy but an old one that has been tried many times before when the left was stronger. It failed each time.” The better course, Smith maintains, is to build an alternative to the Democratic Party — to start a “long struggle to build a new left and a new party that fights for the 99 percent in workplaces, communities and in elections.”

The Socialist Worker published a pair of criticisms, including one titled “Is it Really ‘Our Revolution’?” that argued the group lacks a proper forum for debate or discussion for its supporters and members. “Sanders’ speech [launching the group] did not explain at all what campaign promises these candidates would be expected to make. It was clear that at least the vast majority of them would be running in the Democratic Party, but this issue was never openly discussed,” wrote Daniel Werst, lamenting the lack of any discussion of Green Party candidates. “Candidates marked as ‘progressive’ by Our Revolution have been chosen and will be chosen without any open debate by the membership.”

Our Revolution did not respond to a request for comment.

Noam Chomsky Says Down-Ticket Strategy Holds Promise

Smith and his newspaper raise important questions. But the down-ticket strategy seems to have broad support from many on the left, including radical critics of capitalism and the Democratic Party. ZNet, a website/media organization with strong anti-capitalist views, for instance, aired Our Revolution’s launch video on its website and has urged left writers to focus less on Donald Trump and more on the organization and its prospects. Social critic Noam Chomsky also sees promise in the strategy.

“These [down-ticket approaches] seem to me very sensible initiatives. That’s the way to build an authentic political movement, and it’s not entirely within the [Democratic] party. If it really grows, and the bureaucrats block it, it can take off independently,” said Noam Chomsky in an interview with Truthout. “[It] might succeed in doing what the Greens [members of the Green Party] have lacked interest in doing — one reason why they remain so marginal. I’ve been urging something like this for a long time, as have many others. There have been some good steps in this direction, but the Sanders momentum might make a big difference.”

That Chomsky and the editors of ZNet see promise in Our Revolution reflects one of the ways in which Sanders’ candidacy has transformed politics on the left. In some ways, Sanders provides a bridge between radicals and more mainstream progressives, in a way that Ralph Nader and Jill Stein could not. This potential “unity” should not be overstated, though. As noted, many feel that nothing revolutionary can come in collaboration with the Democratic Party. Much of this skepticism is warranted. But the worst possible approach may be to shun the masses who vigorously trust and support Sanders, his flaws and capitulations notwithstanding, because no revolution is possible without a unified working class.

Vermont: “A Heavy Burden” to Lead

Of course, so much of these debates is still theoretical. But as noted above, in Vermont, the down-ticket strategy is happening already. In addition to the support of Sanders and Our Revolution, Mari Cordes also had the support and endorsement of another local group that is emphasizing down-ticket races: Rights and Democracy, a group in Vermont that was launched in April 2015 and aims to “Bring Bernie’s Revolution Back Home.”

“We feel a great burden as Vermonters, who have been working with Bernie Sanders for years, to show that we can help lead the way in the political revolution,” said James Haslam, who spent 15 years as the director of the Vermont Workers’ Center, which was instrumental in fighting for single-payer health care in the state, before it was abandoned by Gov. Peter Shumlin. “Having a corporate Democrat promise to fight for single-payer to win progressive support and then turning his back on it was a learning experience. We can’t just push politicians, we must have allies in a position to help complement the grassroots work we have been doing for years.”

Cordes also sees her connection to Vermont and Sanders as a “motivating factor” in running for office. “He has been a major inspiration for me on so many issues,” she told Truthout. “I think the most important point he makes is that change comes from the bottom up. If you think about Occupy, some say it fizzled out. I don’t think so. I think it framed the issues beautifully and in a way that made Sanders more appealing. They touched on many of the same themes.”

Cordes is not the only, or even the biggest success story for the movement in Vermont. David Zuckerman, a state senator, is another Progressive Democrat and longtime Sanders ally, who had a big night during the primary. He beat a powerhouse Democrat, speaker of the Vermont House of Representatives Shap Smith, to get the nomination for lieutenant governor.

The lieutenant governor position in Vermont may not be the most consequential job on the planet, but it is often a position that puts candidates in line for a gubernatorial candidacy down the line. And given that the outgoing Vermont governor is best known for abandoning his supporters on single-payer health care, putting someone like Zuckerman in that role could have very real benefits.

The state senator, known for his farming background and long dark hair, said that like Sanders, he felt resistance from the Democratic Party establishment during his primary. As reported by Seven Days, an alternative weekly in Vermont, Zuckerman, “managed to reach voters without the help of the Vermont Democratic Party’s contact list. The party denied him access after he declined to declare himself a ‘bona fide’ Democrat, as he put it, ‘if it means putting the Democratic Party above policy.'”

The reference to a ‘bona fide Democrat’ is another issue fairly unique to the Green Mountain State, which is home to the most viable third party alternative in the country, the Vermont Progressive Party, which was founded during Sander’s campaign for mayor of Burlington in the 1980s. The Progressive Party has members in the State House and in Burlington’s City Hall and in 2008 its gubernatorial candidate finished second to the incumbent Republican Jim Douglas, ahead of the Democratic candidate, Gale Symington.

Zuckerman, who is the first state senator in the party’s history, is now doing what several other candidates have been doing, in part to avoid splitting the tickets and helping the Republicans. He (like Cordes) is running as a “fusion” candidate; he is a Progressive-Democrat, which put him up against Democrats in the primary, while still remaining a Progressive. This approach has its critics, but, as Cordes says, it “rankles the establishment.” It also means these candidates won’t lose votes to the Democrats in the general election (and had they lost, they would not take votes away from the “bona fide Democrats”).

Zuckerman and Cordes, with the support of Rights and Democracy and Our Revolution, will have their day with the voters come Election Day. Should they win it, the victories may be seen as an important part of the “political revolution” Sanders is hoping to start.

Activism in the Post-Bernie Era

Even if Our Revolution is successful in electing its candidates in the coming years, the country will have a lot of work to do. There are many progressive groups and, as Nonprofit Quarterly said, Our Revolution has “a lot to prove.” But whatever its fate, it should not discourage other efforts at mobilization, in and out of electoral politics.

One group, Brand New Congress, also made up of former Sanders staffers and volunteers, is hatching an effort to recruit enough candidates to make sure there is a progressive on the ballot in every single congressional election for 2018. It is a monumental endeavor, and will include, if things go well, bringing candidates to the reddest districts in the country to at least force the incumbents to answer to someone. Saikat Chakrabarti, the Sanders campaign’s director of organizing technology, is heading up this mammoth task. Chakrabarti, who studied computers at Harvard University, told Truthout that when working for Sanders people would always ask him, “If Bernie wins, how is he going to get anything done with the Congress that he has to work with?” Their response to this question is Brave New Congress. “Basically, we’re trying to offer America a big change that can happen immediately in 2018 instead of a long, drawn-out fight to win back congressional seats one at a time,” Chakrabarti said.

Further, and perhaps more importantly, the existence of Our Revolution ought not to discourage more direct forms of resistance. “It is crucial that pressure continues to come at the grassroots, not just in elections,” Zuckerman said. Indeed, at the launch of Our Revolution, Bernie Sanders cited the labor movement, the civil rights movements and other important acts of resistance in America. Most of this change did not come from the voting booth, but from outside of it. In 2008 Howard Zinn decried the “election frenzy” that “seizes the country every four years because we have all been brought up to believe that voting is crucial in determining our destiny, that the most important act a citizen can engage in is to go to the polls and choose one of the two mediocrities who have already been chosen for us.”

Zinn added:

Would I support one candidate against another? Yes, for two minutes — the amount of time it takes to pull the lever down in the voting booth. But before and after those two minutes, our time, our energy, should be spent in educating, agitating, organizing our fellow citizens in the workplace, in the neighborhood, in the schools. Our objective should be to build, painstakingly, patiently but energetically, a movement that, when it reaches a certain critical mass, would shake whoever is in the White House, in Congress, into changing national policy on matters of war and social justice.

If Zinn’s words sound hyperbolic, it is worth noting that his ambitions are not less achievable than what Bernie Sanders proposes, nor are they mutually exclusive. In fact, in some ways, they may be more achievable, since there are so many institutional biases inside the electoral system. The most encouraging part of the Sanders campaign is that, along with concurrent grassroots movements, it demonstrated the scale and intensity of those who wish to fight for social justice. The goal, after all, is not merely better candidates, but a better world.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.