Could the recent mobilization held at Saramurillo in the Northern Peruvian Amazon be remembered as the one that finally brought much needed justice to indigenous peoples affected by over 40 years of irresponsible oil activity? In mid-December 2016, 49 agreements were signed between Peruvian government officials and indigenous peoples. Will things be different this time, will the accords be complied with? In the wake of too many state promises left unfulfilled and the constant oil spills on their territories, hopes are nevertheless high for the thousands of native peoples who united during 117 days in the native community of Saramurillo to demand respect for their rights and to call for an end to the oil destruction of the Peruvian Amazon.

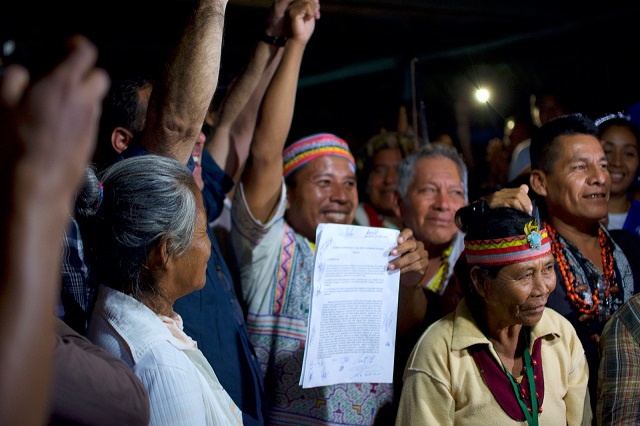

A high level commission headed by Peru’s Prime Minister Fernando Zavala pledges to comply with the agreements in Saramurillo on December 19, 2016. (Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

A high level commission headed by Peru’s Prime Minister Fernando Zavala pledges to comply with the agreements in Saramurillo on December 19, 2016. (Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

Coming from five river basins of the Marañón, Corrientes, Pastaza, Tigre and Chambira, this broad coalition at Saramurillo was formed by different Amazonian peoples such as the Kukama, Urarinas, Achuar, Kichwa and Quechua. Approximately 3,000 people were present at the peak of the protest. All have suffered the impacts of pollution on their territories owing to Peru’s two oldest Amazonian oil fields and pipeline.

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

The agreements concluded this three-and-a-half-month long protest, which began on September 1st 2016. Indigenous peoples sustained a blockade of a section of the Marañón river as a means to press for their demands until November 29th. After several failed attempts at dialogue, and instead of militarizing the conflict, the Peruvian government responded this time by renewing the dialogue on site in Saramurillo with a state commission headed consecutively by Minister of Justice & Human Rights Marisol Pérez Tello, Minister of Energy & Mining Gonzalo Tamayo, and Minister of Production Bruno Giuffra in December 2016. “The main problem here is employment,” affirmed Peru’s Minister of Energy & Mining, “tell me, indigenous leaders, who amongst you haven’t been working for the oil companies?” Hundreds of people gathered at the traditionally built community centre stared at him in silence. Our Executive Director and legal counsellor to the indigenous people Sarah Kerremans testifies: “I almost fell off my chair when hearing the Minister’s opening words to hundreds of indigenous fathers and mothers with exhausted yet hopeful hearts and minds after 117 days of pacific protest. One Achuar leader stood up to break the silence, he was very gentle when he spoke: “We know you duty holders from Lima have difficulties to understand what we really mean, but don’t worry, we will not get tired of explaining our legitimate demands, not even if we have to do so for several days, over and over again. It will necessarily be an intercultural debate.” It was a strong statement that set out the rules for this long debate, which resulted in 49 signed agreements.”

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

The Peruvian region of Loreto — a micro Venezuela, whose local economy has depended upon oil for the past 4 decades, entered a severe economic crisis in 2015 when the international oil price per barrel dropped. Yet the indigenous peoples’ first demands at Saramurillo were not about jobs. Sarah, a fundamental rights specialist who has been involved in numerous dialogues, round tables and prior consultation processes between indigenous peoples and the Peruvian state over the last three years, sees a trend: “This is part of a broader strategy. First of all, the Peruvian state has not been a guarantor for fundamental rights in Loreto for a long time. When indigenous peoples claim their rights after four decades of oil activity on their ancestral lands — fundamental rights such as the right to clean water, their territories and the right to life itself, they are not listened to. There seems to be a tendency to use the idea of jobs creation, or even the so called “empresas comunales” to meet these demands. This might work for a while and does give the impression of direct satisfaction and immediate attention in places where there was little attention before. But after a while, community members see that the problem remains the same over the long term. So one of the main issues put on the table in Saramurillo was not about employment, but rather the immediate and effective remediation of the thousands of contaminated sites in oil lot 192 (operator: Pacific Stratus Energy, former operator Pluspetrol), oil lot 8 (current operator: PlusPetrol) and along the 800 km long pipelines (operator: Petroperu) which cross the Amazon.”

Indigenous leader James Rodriguez Acho speaking during the debate alongside Peru’s Minister of Production Bruno Giuffra. (Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

Indigenous leader James Rodriguez Acho speaking during the debate alongside Peru’s Minister of Production Bruno Giuffra. (Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

Important Agreements for the Past, Present and Future

The process that allowed the agreements was not simple nor was it free of tensions. The debate became a space where indigenous democracy and republican democracy sought to understand each other in order to restore trust and seek justice for the demands. Unlike the usual technical roundtables, the methodology insisted upon by indigenous peoples at Saramurillo was for an intercultural political debate in the presence of a Minister of the state.

The debate between the Peruvian state and indigenous peoples united in Saramurillo, December 2016. (Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

The debate between the Peruvian state and indigenous peoples united in Saramurillo, December 2016. (Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

The Saramurillo accords notably call for the effective remediation of contaminated sites to begin in 2017. Alongside of this, agreements include an independent inspection of the Northern Peruvian Pipeline in the first half of 2017, as well as other pipelines that cross Blocks 192 and 8, with the participation of indigenous representatives.

Peru’s Minister of Energy and Mining, Gonzalo Tamayo, alongside indigenous leaders of federations united in Saramurillo during the debate in late November 2016. (Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

Peru’s Minister of Energy and Mining, Gonzalo Tamayo, alongside indigenous leaders of federations united in Saramurillo during the debate in late November 2016. (Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

“With regards to the pipeline in the Marañon river, we are speaking of an emergency: the rainy season is now underway and the crude from over 12 oil spills last year alone will uncontrollably spread and contaminate the drinking water of the Marañon river, the city of Iquitos, and the Amazon further downriver. The goal of the current government: to continue to exploit oil in the Amazon as soon as possible, despite the corrosion of the old pipelines and despite the many social and environmental problems. So, is that still viable? We hear a new language in the discourse of indigenous leaders in this part of the Amazon and this led to an important agreement to implement a parliamentary commission to discuss this”, comments our Executive Director Sarah Kerremans.

Indigenous peoples returning Petroperu barges back to the pumping station until the debate with the state is completed on December 2016. (Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

Indigenous peoples returning Petroperu barges back to the pumping station until the debate with the state is completed on December 2016. (Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

Under the Saramurillo accords, a community environmental monitoring law and nationwide discussions on Peru’s energy future, in particular with regards to the Amazon region, could see the day through the introduction of a bill by the the Congressional Commission on Andean and Amazonian Peoples, Afro-Peruvians, the Environment and Ecology.

“Oil has not served to improve our Loreto region”, observes Kichwa advisor Jose Fachin. “The economy of indigenous peoples cannot be dependent upon oil activity, neither can Loreto. We want to potentiate our own resources, train ourselves and diversify local economy, and not suffer from pollution. That is why we have to work on an investment plan so that people can improve their quality of life without oil activity, which has been imposed upon us.” In this regard, specific agreements were reached regarding health, education, sanitation, electrification, infrastructure, access to social programs, and a special development plan for various income-producing projects in the communities as compensation for damages. The first stage of this development plan was initiated during a dialogue with a Multisectorial Commission in January 2017, and is due to present its first progress report in June 2017.

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

Accords also aim to investigate the impacts of the four-plus decades of oil operations in Blocks 192 and 8 through the establishment of a Truth Commission involving the government, indigenous organizations and oil companies in order to identify the improvements that can be made.

Not everything was agreements: issues such as land titling in protected areas and payments for easements related to the Petroperú pipeline went unresolved. But even so, through the implementation of the Saramurillo accords, indigenous peoples hope to see concrete results in the immediate, mid and long term since there is a commitment of five years with the current government.

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

More Unity, More Strength

In the face of too many previous agreements left unfulfilled, more unity is the best strategy forward, affirm the indigenous federations united in Saramurillo. Two months on from the signing of the accords, they continue to stand together, ready and vigilant as to the compliance of the accords made by this new government, which “wants do things differently and wants to fulfil” in the words of Peru’s Prime Minister Fernando Zavala during his visit to Saramurillo on December 19th 2016 to pledge government support for the accords.

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

(Photo: Sophie Pinchetti)

Whether there was sunshine or rain, the strategic alliance of these indigenous federations brought together native Amazonian peoples from different languages and ethnicities who ate, slept, laughed, cried, stood strong and hoped side by side. A new horizon, cultural pride and dignity rose through this struggle for territorial defence and their collective and individual rights. “Today, indigenous peoples have united like never before”, declares Shipibo leader and President of ACONAKKU James Rodriguez Acho. “This unity is going to pervade”, insists Achuar leader & President of FEPIAURC Daniel Saboya Mayanchi, “because it is not just the unity of federations or river basins, it is the unity of communities and community members who are at the essence and giving this credibility.”

While the mobilization at Saramurillo on the ground may have come to a close for now, the indigenous unity built during this landmark mobilization is still growing in strengths. This month, more indigenous organizations joined in the platform of the five river basins. The coalition now includes 15 indigenous organizations, each one representing villages affected by oil activity in the Peruvian Amazon. Together, these organizations are uniting to show that their struggle for the land, water and life itself continues.

Watch our short film on the story of Saramurillo, sharing the voices of indigenous peoples united in this struggle. Also available in Spanish language.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.