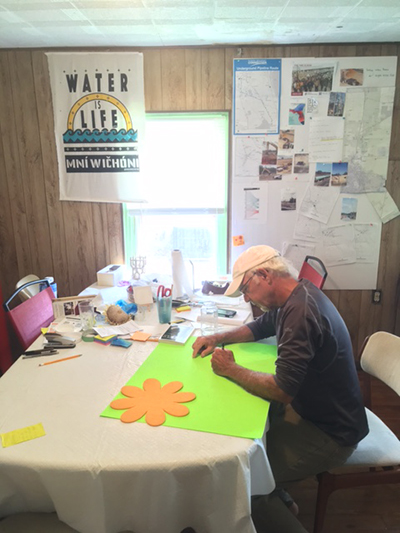

Pete Ackerman, 66, and Kaithleen Hernandez, 21, sit together in a small house in Dunnellon, Florida, with maps and documents splayed out on the walls and the tables around them. They are planning a demonstration for June 9, 2017, which will take place at a large industrial gas compression facility called the Central Florida Hub Compression Station, in Davenport, Florida, 100 miles south of Dunnellon. Ackerman rented the house to serve as an “action center” for those organizing against the large natural gas pipelines being constructed through the southeast United States. They call it the Water is Life House.

Kaithleen Hernandez holds a “Water is Life” sign during a protest against the Sabal Trail pipeline in Florida. (Photo: Pete Ackerma“The location of the demonstration on Friday is symbolic,” Hernandez tells Truthout. “It’s where the Sabal Trail pipeline hooks into the Florida Southeast Connection pipeline. It’s where they are going to turn the gas on. This compression station is the biggest one along the route. You can hear it for miles away.”

Kaithleen Hernandez holds a “Water is Life” sign during a protest against the Sabal Trail pipeline in Florida. (Photo: Pete Ackerma“The location of the demonstration on Friday is symbolic,” Hernandez tells Truthout. “It’s where the Sabal Trail pipeline hooks into the Florida Southeast Connection pipeline. It’s where they are going to turn the gas on. This compression station is the biggest one along the route. You can hear it for miles away.”

Hernandez is referring to Sabal Trail Transmission, LLC — a joint venture of the corporations Spectra Energy Partners, NextEra Energy, Inc. and Duke Energy. The project consists of three separate pipelines: Transco’s Hillabee Expansion Project, Sabal Trail and the Florida Southeast Connection. The biggest and longest of those pipelines is Sabal Trail, a 36-inch, 515-mile long pipeline large enough to pump 1.1 billion cubic feet gas per day. Sabal Trail will carry Marcellus-sourced fracked natural gas piped “backwards” down an existing 10,200-mile Transco pipeline to Alabama, through south Georgia and terminating in central Florida. The Marcellus shale formation stretches across Pennsylvania and West Virginia, and into southeast Ohio and upstate New York, and is the largest source of natural gas in the United States.

Ackerman, a Quaker and former Vietnam War protester, chose Dunnellon as an organizing hub because the town (population 1,700) is a site for one of Sabal Trail Transmission’s large compressor stations. These stations are needed about every 40 to 100 miles along pipelines to re-pressurize the gas. Compressor stations aren’t benign. They release volatile organic compounds (VOCs), particulate matter and other gases. Plus, they’re loud. Many Americans living near compressor stations have reported nosebleeds, trouble breathing, dizziness and nausea, and complain about the 24/7 noise.

Pete Ackerman works at the Water is Life House in Dunnellon, Florida, preparing for Water Protectors’ June 9 action. (Photo: Pete Ackerman)The residents of Dunnellon — which is located in a county that voted overwhelming for Donald Trump, who is now considering easing President Obama’s tougher rules on pipeline safety — aren’t too happy about the pipeline. At a public hearing in 2014, residents from the town turned out in force to voice their concerns and objections, especially about the pipeline running within half a mile of the town’s two public schools.

Pete Ackerman works at the Water is Life House in Dunnellon, Florida, preparing for Water Protectors’ June 9 action. (Photo: Pete Ackerman)The residents of Dunnellon — which is located in a county that voted overwhelming for Donald Trump, who is now considering easing President Obama’s tougher rules on pipeline safety — aren’t too happy about the pipeline. At a public hearing in 2014, residents from the town turned out in force to voice their concerns and objections, especially about the pipeline running within half a mile of the town’s two public schools.

“We’re here for a reason,” Ackerman told Truthout. “This is much more than an environmental issue or an issue just for progressives. It’s a huge safety issue. People are worried and they’re angry.”

Although the company building the pipeline expected the gas to be flowing by now, the pipeline is still inactive. Protests and rallies have been constant during the pipeline construction phase along the entire route. Direct actions have also been common. Water Protectors have anchored themselves together in the pipeline itself, attached themselves to pipeline construction equipment and blocked roads. These actions have forced delays in the project since October of 2016.

Hernandez was one of those who participated in a direct action. She was arrested with Alexa Oropsea in January of 2017 for locking themselves together under a Sabal Trail pipeline truck that was hauling equipment to finish construction on a segment of the pipeline.

“I Had to Do Something”

“I was born in Miami. I’ve seen the effects of climate change first hand. This state is on the front lines and I have to do something about it,” Hernandez told Truthout from the Water is Life House. “Not only is this about climate, but I saw what was happening in North Dakota with [the Indigenous-led resistance to] DAPL, and I knew what I had to do. I had to do something here.”

In October of 2015, before Sabal Trail received a permit to construct, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) outlined “very significant concerns” about the proposed route. In a letter to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the agency in charge of oversight and permitting of the pipeline, the EPA recommended that the pipeline be rerouted to avoid more than 1,000 acres of wetlands, the Floridan Aquifer, which supplies drinking water to 20 million people in Florida, Georgia and other environmentally sensitive areas.

The Floridan Aquifer is located in a sensitive and unique geological formation called karst, which is a special type of landscape that is formed by the dissolution of soluble rocks. Karst regions contain aquifers that are capable of providing large supplies of water. However, the characteristics of karst geology also make the region susceptible to ground subsidence (the collapse of land), sinkhole collapse and groundwater contamination.

The pipeline tunnels under 699 bodies of water (including lakes, rivers and streams) and 1,958 wetland systems. It winds through farmlands and forests, through small and large towns and near schools. More than 80 percent of people that live along the route are in impoverished neighborhoods and communities of color.

Bobby Billie, a sixth-generation Seminole and clan leader of the Council of the Original Miccosukee Simanolee Nation Aboriginal Peoples, has been actively fighting the Sabal Trail pipeline. He stands at the Fort Drum Creek, an important cultural place for his people, where the Sabal Trail pipeline was drilled through. (Photo: Shannon Larsen)The pipeline also crosses culturally important and historic territories important to Florida’s tribes. In early January, the Seminole Tribe of North Florida opened four “heartland” protest camps along the pipeline route encouraging people to act as Water Protectors and to observe the pipeline construction and document violations that they witness.

Bobby Billie, a sixth-generation Seminole and clan leader of the Council of the Original Miccosukee Simanolee Nation Aboriginal Peoples, has been actively fighting the Sabal Trail pipeline. He stands at the Fort Drum Creek, an important cultural place for his people, where the Sabal Trail pipeline was drilled through. (Photo: Shannon Larsen)The pipeline also crosses culturally important and historic territories important to Florida’s tribes. In early January, the Seminole Tribe of North Florida opened four “heartland” protest camps along the pipeline route encouraging people to act as Water Protectors and to observe the pipeline construction and document violations that they witness.

Florida Indigenous leader Bobby C. Billie, a sixth-generation Seminole and clan leader of the Council of the Original Miccosukee Simanolee Nation Aboriginal Peoples, has been actively fighting the Sabal Trail pipeline.

He watched as the pipeline companies tore through culturally and environmentally important areas to the tribe such as Fort Drum creek in central Florida. On January 23, 2017, Billie led a rally at the Florida state capital in Tallahassee where protesters called for FERC, the Army Corp of Engineers and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to revoke Sabal Trail’s permits.

“We cannot just leave things the way they are,” Billie told Truthout. “If we do, it will affect the future of all life. … We need to get together and do something about it. Gas and oil does not belong on top of the Earth. It belongs from where they dug it up.”

Shannon Larson, who works closely with Billie, has documented the damages to Fort Drum Creek and other important sites. They just recently returned to the site where the pipeline was drilled through the Fort Drum creek.

The Sabal Trail pipeline being constructed through the sensitive wetlands around Fort Drum Creek. All Cypress trees within the right of way were cleared and Oak trees that were several hundred years old were cut down. (Photo: Matthew Schwartz)

The Sabal Trail pipeline being constructed through the sensitive wetlands around Fort Drum Creek. All Cypress trees within the right of way were cleared and Oak trees that were several hundred years old were cut down. (Photo: Matthew Schwartz)

“I just broke down. It’s just devastating that it will never be back the way it was before. The sounds of the animals are gone. The birds are gone. It’s just devastating,” Larsen told Truthout.

Activists are not just worried about the potential direct impacts to water if the pipeline breaks. They’re also worried about the large amounts of natural gas that natural gas pipelines release directly into the atmosphere. “If we do not do something, the rich people making the money off of oil and gas, they are going to kill us all,” Billie told Truthout. “The money is not going to save us. That is just imagination, a dream. And by the time we wake up, it is going to be too late.”

In a recent study completed by the Environmental Defense Fund, scientists estimated that annual emissions of about 80 billion cubic feet are escaping every year from thousands of key nodes along the nation’s natural gas interstate pipeline system. This equals the 20-year climate impact of 33 coal-fired power plants.

Even though all these risks were studied and acknowledged by the EPA’s own scientists, two months after sending the letter, the agency abruptly reversed course and said after meeting with representatives of Sabal Trail they believed the company “fully considered avoidance and minimization of impacts during the development of the preferred route.”

In February of 2016, FERC issued Sabal Trail Transmission a certificate of public convenience and necessity to construct and operate the Sabal Trail pipeline.

Since construction began in September of 2016, a man has been shot and killed by Florida police after shooting a rifle at the pipeline, farms have been damaged and destroyed, thousands of people have attended protests and rallies organized along the route, dozens of Water Protectors have been arrested for taking direct action to stop the pipeline and lawsuits have been filed.

The properties of hundreds of private citizens have been condemned. In one of the most publicized cases, two brothers, James and Robert Bell, in Mitchell County, Georgia, who owned 100 acres of land were sued by Sabal Trail, LLC, under Florida’s eminent domain law. The brothers lost but then counter-sued the pipeline company for trespassing, saying Sabal Trail contractors entered their land without consent. Again, the brothers lost. The judge awarded Sabal Trail $47,000 in legal fees for defending the trespassing accusation.

“It is my contention they are going to use this brief, this judgment, to bully anybody and everybody who stands against them,” James Bell told WABL News after the hearing.

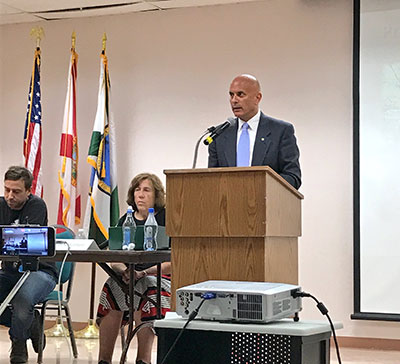

Tim Canova is a law professor at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale and chair of Progress For All, a community action group in Hollywood, Florida. He is nationally known for taking on Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz, the former head of the Democratic National Committee, in the 2016 Florida primary, losing in November by only 6,000 votes. He’s leading the political fight against the Sabal Trail pipeline and is angry that Sabal Trail was given authority by the federal government to use eminent domain to build the pipeline.

Tim Canova moderates a Sabal Trail pipeline forum in Hollywood, Florida, on May 23, 2017. Cecile Scofield, an expert on liquid natural gas facilities, also presented. (Photo: Geoff Campbell)“Eminent domain is supposed to be the taking of private land for public use, not for private use. They gave this power to a private consortium,” Canova told Truthout. “You know something’s wrong there.”

Tim Canova moderates a Sabal Trail pipeline forum in Hollywood, Florida, on May 23, 2017. Cecile Scofield, an expert on liquid natural gas facilities, also presented. (Photo: Geoff Campbell)“Eminent domain is supposed to be the taking of private land for public use, not for private use. They gave this power to a private consortium,” Canova told Truthout. “You know something’s wrong there.”

John Quarterman, head of the WWALS Watershed Coalition — which advocates for the Withlacoochee, Willacoochee, Alapaha, Little and Suwannee River watersheds — has fought the Sabal Trail pipeline since it was first announced in 2013. He points to many different incidents in which the pipeline company has damaged the environment and the people in the communities it goes through. He documented these offenses on WWALS’s website. The real kicker, Quarterman says, is that the reason the utilities gave for needing the pipeline is completely bogus.

“This pipeline is totally unnecessary and [its unnecessary nature] was admitted to by Florida Power and Light. They stated in their 10-year plan they submitted to the Florida Public Service Commission (PSC) in 2016 they need no new electricity capacity until 2024 and yet extra capacity was the justification they used to receive FERC permit,” Quarterman told Truthout.

While Florida utilities were fighting to secure permits for the Sabal Trail pipeline, they were also fighting to make it more difficult for Floridians to put solar panels on their rooftops, spending more than $20 million in 2016 attempting to amend Florida’s constitution to impose new barriers to the expansion of rooftop solar energy generation. A handful of other groups, heavily financed by utilities, spent another $6 million promoting the amendment. In November, voters rejected the proposed amendment. The utilities gave at least $9 million to legislative campaigns and to Republican Gov. Rick Scott.

“Elected officials don’t represent the people anymore, they represent the fossil fuel companies,” Canova said.

Even though Florida is the “Sunshine State,” it lags way behind in solar development, in no small part due to lobbying efforts by Florida’s big utilities. According to the Florida Public Service Commission’s 10-year site plan, utilities plan to increase their solar generation, but solar will make up only a tiny fraction of all energy generation supplied by the regulated utilities in the next 10 years. According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), about nine-tenths of planned new electrical capacity is natural gas-fueled and one-tenth is renewable, mostly solar. This is despite the fact that Florida ranks third in the nation for rooftop solar potential.

As the utilities were throwing millions into fighting distributive solar, they were also trying to get residents of Florida to pay for their new natural gas pipeline, the Sabal Trail.

A map of the southeast pipeline project consisting of three separate pipelines — Transco’s Hillabee Expansion Project, Sabal Trail and the Florida Southeast Connection. (Map: Sable Trail Transmission, LLC) Guaranteed Rate of Return

A map of the southeast pipeline project consisting of three separate pipelines — Transco’s Hillabee Expansion Project, Sabal Trail and the Florida Southeast Connection. (Map: Sable Trail Transmission, LLC) Guaranteed Rate of Return

“The narrative I see here is that the fossil fuel industry is addicted to their guaranteed rate of return — 10, 11 percent rates of return — and it doesn’t want to start converting to solar because it will start to diminish the profitability of their existing investments,” Canova told Truthout.

What is that guaranteed rate of return for Florida Power & Light (FPL) and Duke Energy on the Sabal Trail pipeline? Precisely 11.6 percent.

“New pipelines are capital-intensive and expensive,” Jonathan Peress, a natural gas and electricity market design expert with EDF, said in an interview with Truthout. “The Sabal Trail pipeline was designed to spread the costs of the pipeline on captive ratepayers.”

To get that $3.2 billion they needed to build the pipeline from Florida residents, the utilities argued that Sabal Trail was necessary to meet future electricity demand in the state even though they directly contradicted that statement in the 10-year plan they submitted to the PSC. The PSC consists of five members, all directly appointed by Republican Gov. Rick Scott, who has a financial stake in Spectra Energy, one of the pipeline builders. They voted to allow FPL and Duke Energy to make Florida ratepayers pick up the tab.

In other words, the utilities aren’t taking any of the risk for investing in new infrastructure; the public is. Peress sees what he calls a “disturbing trend” of utilities imposing costs on ratepayers so that their affiliate companies, in this case Sabal Trail Transmission, LLC, can earn shareholder returns. Ratepayers costs are being converted into shareholder return.

Peress pointed out existing pipeline capacity isn’t even being used. According to a 2015 US Department of Energy report, average pipeline capacity utilization for the interstate pipeline system between 1998 and 2013 was only 54 percent.

Even those in the pipeline industry agree. Kelcy Warren, the infamous CEO of Energy Transfer Partners, the natural gas and propane company behind the Dakota Access pipeline, and based in Dallas, Texas, stated at an August 2015 earnings call that, “The pipeline business will overbuild until the end of time.”

“Why not overbuild,” says Canova. “Especially if they can get the public to pick up the tab?”

Although, as Matthew Schwartz from the South Florida Wildlands Association points out, FPL and Duke Energy are aggressively building new natural gas plants along the route of the Sabal Trail including one in Okechobee, Florida; one in Citrus County, Florida; and one still in the permitting process in Hendry County, Florida.

“The pipeline will bring in cheap fracked natural gas,” Schwartz told Truthout, adding that the pipeline “is basically creating a complete dependence of our energy infrastructure on natural gas for years to come and is becoming impossible to move us in a serious way into what Florida has an abundance of, which is solar energy.”

Advocates for renewable energy and Water Protectors see the Sabal Trail pipeline being used by Florida’s utilities to increase Florida’s reliance on natural gas but also as a way to export the gas in liquid form overseas.

Liquid Natural Gas Exports

According to the EIA the United States is expected to become a net exporter of natural gas by 2018. This trend is driven partly by the building of new liquid natural gas export facilities and the glut of natural gas being drilled in the US. Prices overseas are higher than what companies get in the United States. Liquid natural gas is volatile and dangerous. If the liquid is spilled, it expands rapidly and can catch fire when it hits the air. This type of fire burns extremely hot and cannot be extinguished. In 2014, there was a blast at a liquid natural gas facility in rural Washington State that injured workers and forced an evacuation of everyone within a two-mile range of the facility. This came after the deadly 2010 natural gas pipeline explosion that killed eight people in San Bruno, California.

Cecile Scofield spent years fighting a liquid natural gas facility in Fall River, Massachusetts, in the early 2000s. She was eventually successful. When she moved to Florida in 2009, she never dreamed she would find herself in the middle of a liquid natural gas facility construction boom.

“What no one is talking about is that a lot of these [liquid natural gas] facilities being built all over Florida have no one watching over them,” Scofield told Truthout. “After FERC walked away, Floridians are left with no oversight. No one making sure they are sited correctly. No one making sure they are safe.”

Scofield is referring to a decision made on September 4, 2014, by FERC that was almost completely ignored by the media besides industry publications. FERC issued an order that “disclaimed jurisdiction” over liquefied and compressed natural gas operations that were not directly on the water.

In other words, says Scofield, anything built inland and then trucked or moved by rail to sea for export is now out of the commission’s jurisdiction.

“Ultimately, their decision means that most of these new [liquid natural gas] facilities being built in Florida right now have no oversight from anyone, in the siting, construction or safety,” Scofield told Truthout. “The FERC process wasn’t perfect, but there were requirements, exclusion zones and standards. I could request and find important safety information. I could get a feel for the project. Now, nothing.”

Norman Bay, a former chair of FERC, vehemently disagreed with the decision to “disclaim jurisdiction,” and wrote a scathing dissent. Because of that decision, new inland liquid natural gas facilities have sprung up all around Florida and more are being proposed. Most can be easily connected to the Sabal Trail pipeline. Once the gas is liquefied, energy companies then truck it or move it on trains to a port to be exported.

Although FERC has never turned down a permit for a liquid natural gas facility, without its oversight in siting and construction, Florida has turned into an unregulated mine field of liquid natural gas exports, with small facilities popping up in neighborhoods, close to schools and hospitals, with little to no oversight.

“I’m scared to death. This is a travesty. I expect the government to protect the public and they’re just not,” Scofield told Truthout. “There is no way most of these facilities would pass muster in the FERC process.”

“We Are Living Victory”

On the June 9 day of action, when Hernandez and Ackerman plan to gather with hundreds of others at the Central Florida Hub Compression Station, in Davenport, Florida, they hope to raise even more awareness about the pipeline and build power for the fights to come.

“The gas isn’t on yet,” said Hernandez. “We can help give more time for the legal fight to proceed. It’s important to harness the energy from these events and build community. It’s important we don’t lose sight of what we are fighting for. We are the light at the end of the tunnel. This isn’t just about one pipeline. It’s up to us to come together and keep this movement going.”

On March 23, Sierra Club and the Gulf Restoration Network asked FERC to halt construction of the Sabal Trail pipeline. They requested that FERC “correct its use of materially false or inaccurate information to authorize the project; prepare a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement; and stay construction and operation of the Project pending completion of the actions.”

Previously, on September 16, 2016, the Sierra Club, Flint Riverkeeper and Chattahoochee Riverkeeper filed a lawsuit in the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia challenging FERC’s approval of the project, arguing that FERC failed to analyze the climate impacts of the project and the power plants it would serve, and also failed to adequately analyze alternate routes that would have less impacts on the environment and communities of color. That lawsuit is still pending.

Ackerman knows what they are up against, but he’s not daunted. He points to the ways in which pipeline resistance efforts around the country — and the world — are connected.

“We aren’t a bunch of isolated independent struggles,” he said. “We are united in this effort, not only in this country but worldwide. We are living victory. We know what the future is going to be and it’s not going to be fossil fuels.”

Canova is also looking to the future.

“I’ve had people say, what’s the point, why keep fighting? It’s already built. And maybe they have a point — and yet we got to keep fighting it to the very end,” he said. “We’ll have to convert to solar and wind and alternative energy sources eventually. People know that is what is needed.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $24,000 by the end of today. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.