Julia Boss’s daughter was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in 2015, just before her ninth birthday. Like many people who are self-employed, Boss purchased a health insurance plan through the federal marketplace with high out-of-pocket costs. Until she reached a $6,000 deductible, Boss paid $251 for a vial of insulin and $381 for a box of cartridges for an insulin injection pen that her daughter uses at school. Boss also paid $198 for emergency glucagon kits that could save her daughter’s life should her blood sugar levels suddenly drop.

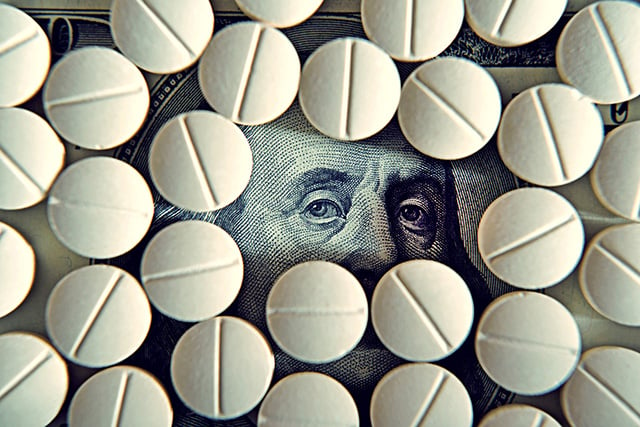

Boss had no choice but to pay huge costs to keep her daughter alive. Her story echoes many that have emerged in media coverage over the past year as public outcry grows over rising prescription drug prices. Notorious cases of price gouging by the likes of Valeant Pharmaceuticals, Mylan and Martin Shkreli have drawn plenty of media attention and left the public fuming, but greedy pharmaceutical executives are not the sole focus of Boss’s frustration. Boss says insurance companies have been lying to her — and the rest of us — about drug prices, and she found herself paying more than her insurance plan does for insulin before hitting her deductible.

“[I feel] cheated and lied to, yes,” Boss told Truthout. “Though devastated might be the best word.”

When it comes to insulin and other pharmaceuticals, drug companies are not competing to offer consumers the lowest price, they are competing to offer benefit managers the highest rebate on list prices.

In 2016, Boss switched from a “bronze” to a “silver” insurance plan with a higher premium and lower deductibles, but drug companies had also raised the price of insulin and glucagon, so she still paid hundreds of dollars out of pocket each month until hitting a $4,100 maximum. After moving her family from Washington to Oregon, Boss briefly paid a $50 copay for insulin cartridges before her daughter developed an allergy to the product and was forced to switch to another brand that was not preferred by the insurance company.

“By then I had started to notice how uncomfortable the pharmacists looked when I picked up my daughter’s prescriptions, and I had started following #insulin4all activists on Twitter — people who have been working hard for years to bring public attention to insulin prices,” Boss said. A storm was certainly brewing on social media, where diabetes patients were regularly posting pictures of their receipts from the pharmacy.

“I’ve seen [social media] posts from people who go to pick up insulin at the pharmacy, field the pharmacist’s inevitable, ‘you do know the price on this?’ question, and then go out to cry in the car,” Boss said. “Every one of those people feels cheated, especially when they know insulin prices have increased by over 1,000 percent in 20 years.”

In November 2015, Boss founded the Type 1 Diabetes Defense Foundation (T1DF), a group determined to get to the bottom of high insulin prices and hold the profiteers accountable.

Secret Drug-Pricing Deals Keep Consumers in the Dark

Like other specialty drugs, insulin prices have risen dramatically in recent years and continue to go up like clockwork. For example, Eli Lilly and Co. raised the price of Humalog, a fast-acting form of insulin that Boss’s daughter used before developing an allergy to it, from $2,657 per year to $9,172 from 2009 to 2017: a 345 percent increase. Along with competing insulin manufacturer Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly raised the price of its flagship insulin product again this year, despite government investigations into pricing schemes and class-action lawsuits accusing the companies of price-fixing.

Why are insulin prices so high? Boss says that in order to answer this question, we must examine the relationship between drug manufacturers and insurance companies. There are actually two prices set for insulin and other specialty drugs: the “list price” put on the open market by manufacturers like Eli Lilly, and the “net price” insurance plans pay after extracting fees and hefty rebates from manufacturers. T1DF estimates these backroom deals cut between 50 to 75 percent off the list price of various insulin products, based on market reports and public statements by pharmaceutical companies. That means Boss’s insurance plan was paying much less for insulin than Boss paid out of pocket before meeting her deductible.

This isn’t just the case for insulin. Data compiled by the IQVIA Institute of Human Data Science shows that the net prices insurance companies pay for most drugs are increasing at much slower rates than the list prices that consumers without insurance (or consumers who haven’t yet met a deductible) would pay out-of-pocket at the pharmacy.

Rebates lowering the net price of a drug much lower than its original list price are negotiated by companies called “pharmacy benefit managers,” which oversee prescription drug plans for employers and insurers. Benefit managers like CVS Caremark and Express Scripts control the formularies, or lists of specific brand name and generic drugs, offered to members under insurance plans, so they can demand fees and deep rebates from manufacturers in exchange for access to millions of customers.

Pharmacy benefit mangers typically profit from a percentage of the rebates they pass on to insurers, and a lack of transparency in their pricing systems has generated controversy in recent years as observers raise questions about whether savings are actually passed on to patients that need them. The federal government and several states have launched investigations into deals struck between manufacturers and pharmacy benefit managers.

So, when it comes to insulin and other pharmaceuticals, drug companies are not competing to offer consumers the lowest price, according to TIDF. Instead, they are competing to offer benefit managers the highest rebate on list prices. The higher drug companies set their list prices, the higher the rebate they can offer benefit managers. This feedback loop explains why the price of insulin keeps going up even though the drug has been around for decades.

A trio of lawsuits filed by T1DF earlier this year goes even further, alleging that manufacturers and pharmacy benefits managers acting on behalf of insurers have illegally conspired to use this “kickback scheme” to inflate the price of insulin, blood sugar test strips and emergency glucagon kits under secret agreements in order to maximize profits on both sides. Patients with high deductibles and copays are gouged as a result. A separate lawsuit alleging the insulin manufacturer Novo Nordisk misled investors about secret rebate deals with pharmacy benefit managers makes similar claims.

How Insurance Companies Mislead Their Customers

Drug manufacturers paid about $179 billion in rebates in 2016, with 30 percent going to government programs like Medicare and 50 percent used to place drugs on insurance formularies, according to analysts at Credit Suisse. Analysts estimate about 90 percent of the rebates secured for insurers by pharmacy benefit managers are “recycled” back into the system in order to reduce insurance premiums. However, the amount that actually trickles down to consumers is currently up for debate. Insurers often use high list prices to calculate pharmacy benefits rather than the lower net prices secured with rebates. Meanwhile, the rebating system is pushing list prices of specialty drugs like insulin higher and higher.

Insurance plans with low copays and deductibles shield many people from ever-increasing drug prices, but people with no insurance or plans with high out-of-pocket costs like Julia Boss face excruciating prices when they go to the pharmacy. In fact, T1DF claims this system leaves some people living with diabetes and other chronic conditions paying more for drugs than insurance companies do — even if they have insurance. Alex Azar, a former Eli Lilly executive and President’s Trump’s latest nominee for health secretary, admitted as much in a speech at the conservative Manhattan Institute last year.

Boss says insurance companies get away with this because price negotiations between manufacturers, benefit managers and insurers are done in secret, and insurance plans do not disclose the post-rebate “net price” they actually pay for drugs to their customers. Instead, when patients check their insurance drug benefits, they see drug prices that are much closer to the original list price that manufacturers start with before the backroom negotiations and rebates bring the net price down.

“In the current system, insurers are misleading all their customers, even those who don’t pay based on list price,” Boss says.

Under this system, Boss explains, both consumers with great insurance (low deductibles and copays) and those with barebones coverage see a higher drug price than their insurer actually pays when they check their benefits. Here’s how Boss put it in an email to Truthout. Remember, the “list price” is the original cost of a drug set by manufacturers, and “net price” is the price insurers actually pay after secret rebates:

Imagine what would happen if insurers instead reported net cost to plan in that column (that’s possibly $70 or less for a 10 ml vial of analog insulin with list price $270, based on current rebating estimates). The marketing executive would know her insulin prices aren’t breaking the employer’s bank, and would keep that in mind when she’s asking for a raise. The Affordable Care Act-insured freelancer who’s paying $270 for every vial of insulin that keeps her child alive would ask, “what in the world is happening to the other $200?” And the landscaping worker with no health insurance would ask why he’s paying a $300 cash price for a life-saving medicine that costs insurers only $70.

This is particularly harmful for people with diabetes, and not just because some patients cannot afford drugs they need to survive. Under this system, it’s easy for people to blame their co-workers with chronic conditions for driving up insurance prices for everyone else on an employer’s plan, when in fact drug prices have been inflated by a secret system of kickbacks negotiated behind closed doors by wealthy corporations. This has also allowed conservatives to blame rising premiums under the Affordable Care Act on the same people who have been devastated by discriminatory drug pricing, according to T1DF.

Meanwhile, when people living with diabetes and other chronic illnesses cannot afford the medicines that keep them healthy, they are more likely to end up in the hospital with severe complications, driving up health care prices and premiums for everyone else.

The sheer opacity of the drug-pricing system allows all the players to deflect blame onto each other while protecting their individual profit margins. Pharmaceutical companies have received the most heat from lawmakers and the media, but they say they need to set high prices to pay for rebates negotiated by pharmacy benefit managers on behalf of insurance companies. Pharmacy benefit managers claim they save consumers billions, but last week the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry’s main lobbying group released a report suggesting that insurance companies are not passing these savings on to their customers. Rebates and discounts have grown over the past decade, but workers with employer-sponsored coverage have seen out-of-pocket spending on deductibles and coinsurance rise by 230 percent and 89 percent, respectively.

When Truthout asked insurance industry group America’s Health Insurance Plans about the report, spokeswoman Cathryn Donaldson pointed a finger back at manufacturers.

“The bottom line is, the original list price of a drug — which for many drugs is set not by the market, but solely determined by the drug company — drives the entire pricing process,” Donaldson said. “And if the original list price is high, the final cost that a consumer pays will be high. It is that simple: The problem is the price.”

The focus on rebates, Donaldson said, is a “deliberate tactic” to obscure more serious issues around transparency and lack of competition among drug companies. However, she did not address questions about the insurance industry’s practice of reporting those high list prices to their own customers, even when insurers are not paying them.

Of course, the pricing scheme that drives up the price of insulin and other drugs is not the only reason why people in the United States pay some of the highest drug prices in the world. Pharmaceutical companies are always looking for ways to extend the life of their patents, and laws barring the re-importation of drugs prevent US customers from finding cheaper options in neighboring countries. Expect all of these issues — including secret rebate negotiations — to come up this week when the House Energy and Commerce Committee calls insurers, manufacturers and benefit managers into a hearing examining the drug supply chain. An emerging debate over proposed reforms aimed at increasing transparency in Medicare’s drug program is also expected to thrust the issue into the limelight.

If policymakers do their homework, it may only be a matter of time before consumers learn the truth about high drug prices.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.