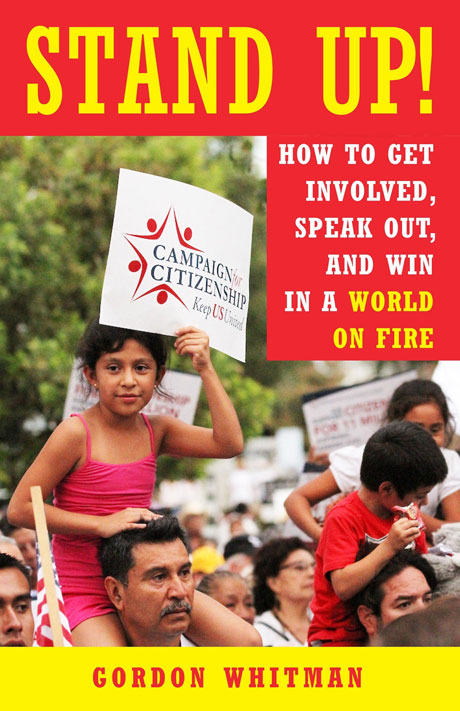

Are recent election results in Alabama, Virginia and New Jersey a sign that resistance to Trump will reshape American politics? In Stand Up! How to Get Involved, Speak Out, and Win in a World on Fire, veteran organizer Gordon Whitman argues that the only way to move from protest to power is through the kind of face-to-face organizing that has powered every successful social movement in US history. As Congressman Keith Ellison says about this new book, “Grassroots organizing is our best hope. If you’re serious about making change from the bottom up, read Stand Up! and pass it on.”

The following is an excerpt from the introduction of Stand Up! How to Get Involved, Speak Out, and Win in a World on Fire:

Each of us faces a moment of truth when we have a chance to take a risk for something larger than ourselves. Sometimes the knock at our door asking us to stand up, get involved, speak out, take leadership, do something is so faint we miss it. Other times we hear the knock but we aren’t sure how to respond. Is it really for me? Am I the right person? Won’t someone else step forward?

The knock at Mario Sepulveda’s door was unmistakable. It came as a deafening explosion of falling rocks. On August 5, 2010, Mario was operating a front-end loader, deep in a one hundred-year-old copper mine in Northern Chile. After years of neglect — which had led to scores of workers losing limbs and lives — the mine finally collapsed, trapping Mario and thirty-two other miners two thousand feet underground.

In the minutes that followed the collapse, some men ran to a small reinforced shelter near the bottom of the mine. Without thinking ahead, they broke into an emergency food supply cabinet and began eating the meager supply of food meant to keep two dozen miners fed for just two days. Other miners went searching for their comrades. Once the mine settled, a small group, including Mario, explored narrow passageways looking fruitlessly for a way out. The shift supervisor took off his white hard hat and told the others that he was no longer their boss. Now they were all in charge.

Amid the fear and confusion, Mario began organizing the other miners. He’d seen the massive slab of rock blocking their escape. Later, he told Héctor Tobar, author of Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine, and the Miracle That Set Them Free, “At that moment I put death in my head and decided I would live with it.” Mario told the men (women weren’t allowed to work in the mine) that they might be underground for weeks. They needed to ration their cookies and condensed milk. Once they accounted for all thirty-three miners, he reminded them that that number was the age at which Jesus was crucified, a sign that they were meant to live. He encouraged them to organize daily prayer meetings, which brought the men closer and helped them overcome the frictions of being buried alive with little hope of rescue.

Mario was not alone in taking leadership. One of the most important actions that he and the shift supervisor took was to give every man a role — from setting up lighting to mimic day and night, to carting water and caring for the sick. The men organized daily meetings where they debated and voted on life-and-death decisions about rationing their food and organizing their living space. Above ground, their mothers, sisters, and wives organized to put pressure on the Chilean government, which dragged its feet before mounting a full-scale rescue. The miners’ survival was a team effort.

Yet Mario’s decision to stand up on the first day likely saved his own and the other men’s lives. By carefully rationing their meager supply of food, they were able to survive for weeks on daily crumbs. As important, by organizing themselves, they preserved their humanity. They sustained the belief that they would ultimately escape their underground tomb. When some men gave up hope, others pushed them to keep fighting to stay alive.

Few of us will experience the extreme deprivation faced by the Chilean miners during their sixty-nine days underground. Yet the challenges they overcame — finding a way to share scarce resources, keeping hope alive despite repeated setbacks, not lashing out at the people around them — are similar to those we grapple with in our own lives. And, like the miners, we all ultimately depend on one another for our survival.

Today, in one way or another, almost all our lives are being made less secure by three inter-connected crises — growing economic inequality, hardening racism, and accelerating climate change. These are the equivalent of the falling rocks and darkness that put the Chilean miners to the test. Like the mine collapse, the changes that are pulling our society and planet apart are not simply the result of unfortunate accidents. They flow from decades of disinvestment from people and communities. They are the result of intentional political decisions that have used racism to pit us against each other and concentrated wealth and power in the hands of a small number of people at the expense of everyone’s safety and wellbeing.

Just as the miners had to face the reality that there was no simple way out of the mine (one of the many safety violations found was the lack of escape ladders), we need to recognize that conditions are not going to get better by themselves. No one is coming to save us. There’ll be no hero on a white horse. There is no app, no high-tech solution. All we have to fall back on is one another, our human capacity to organize ourselves to create a better society.

Once we decide to stand up and speak out, we’re entering a world of wolves, of powerful forces that want us to keep quiet or disappear. They will not give up their privilege without a fight. We need to bring all the wisdom we have about how to make change. We cannot rely on good intentions or use Band-Aids to treat the symptoms but not the sickness. We need to bring people who are on the sidelines into public life so we have enough people power to win. We need organizations and movements with leverage to negotiate changes in the laws and policies that shape our lives. We need to be able to govern our communities, states, and countries. That political work can be aided by technology. But it succeeds only through the kind of face-to-face relationships that have sustained every social movement in history.

We have the power we need to create a just and fair society. People who profit off misery tell us to suck it up. “This is just the way it is. You can’t fight city hall. Your voice is irrelevant.” This is a lie, no truer than the idea that some people are worth more than others. There is almost nothing we cannot change — if we choose to get involved, if we open our hearts to others, if we see that this isn’t about helping another person, but about our own liberation, if we don’t try to do it alone, if we learn from those who’ve risked their lives to fight oppression, if we have the courage to confront people in power even when we’re uncertain or scared.

To shift the balance of power in our society, many more people need to let go of the idea that nothing can be done or that they have nothing to offer. When we hesitate to engage in politics as more than dissatisfied voters, we hand our power to those who are already powerful. We live in a society that tells us that we’re on our own, even as a small number of corporate executives exercise outsized control over our lives. Over the past forty years, the people who run the largest companies in the world have succeeded in depressing wages for most workers, increasing profits, and shrinking government as a safety net in hard times. These changes have caused great suffering and shorter life spans. They’ve also cut us adrift from each other. We distrust not only big institutions but also one another and ourselves. We seek community but doubt it exists. We want our voices to be heard but question if anything can change.

I wrote Stand Up! as a tool to help interrupt this cycle of cynicism. When we organize, we experience being an agent of change rather than an object of someone else’s imagination. This is about more than just being good people. It’s about our survival. In a society where wealth is ever more concentrated and the planet is at risk, opting out is not an option. If we don’t act now, our lives and those of our children and their children will be immeasurably diminished. It will become increasingly hard to afford higher education, find stable work, and walk the streets without fear of violence.

Ella Baker — the organizing conscience of the civil rights movement — said about her work, “My basic sense of it has always been to get people to understand that in the long run they themselves are the only protection they have against violence and injustice.” That means nurturing people’s capacity to lead their own organizations. As she said, “Strong people do not need strong leaders.”

Stand Up! offers a step-by-step framework for becoming an effective social-change leader and building better organizations. It’s designed to motivate more people to dive in and take greater risks for racial and economic justice. If you are already involved in social change, the book is meant to help deepen your commitment — to answer the question, How do I make a life out of this justice work and bring others with me?

Five Conversations That Can Change the World — and Our Lives

Stand Up! is structured around five conversations that can help people build and lead powerful organizations. Our capacity to talk with one another is the most reliable tool we have for changing the world. We all know the difference between a lecture and a conversation. When we talk at people rather than with them, most people will take a pass. Some may show up again or respond to the action we asked them to take, but their commitment is unlikely to grow. Any results will probably be short-lived. We need to engage in dialogue with people if we want to see them develop into leaders or to build organizations that can persist against powerful foes.

Conversations take time and can be difficult. They’re powerful because they create a “pool of shared meaning” that makes it possible for people to think together. The choices we make about strategy and tactics are better when they stem from dialogue. People feel a sense of ownership and responsibility for them. Social change boils down to building durable human relationships that make it possible for large numbers of people to act with power and purpose — which is why Stand Up! is structured around conversations.

Each of the five conversations in the book is meant to make us better leaders, more aware of our emotions (purpose), clearer about the experiences and values that drive our choices (story), able to build closer relationships across difference (team), more powerful in the world (base) and more courageous and effective in confronting oppression (power). These are habits of the heart. They help us become better people, with greater awareness and consciousness in the world. The conversations and the practices that flow from them are not magic solutions though; they’re things we already know instinctively, but don’t always do under stress. That’s why they need to be practiced and repeated (wash, rinse, repeat) so they become who we are and what other people expect from us.

Note: Footnotes for this excerpt can be found in the book .

Copyright (2017) by Gordon Whitman. Not to be reposted without the permission of Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $50,000 in the next 10 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.