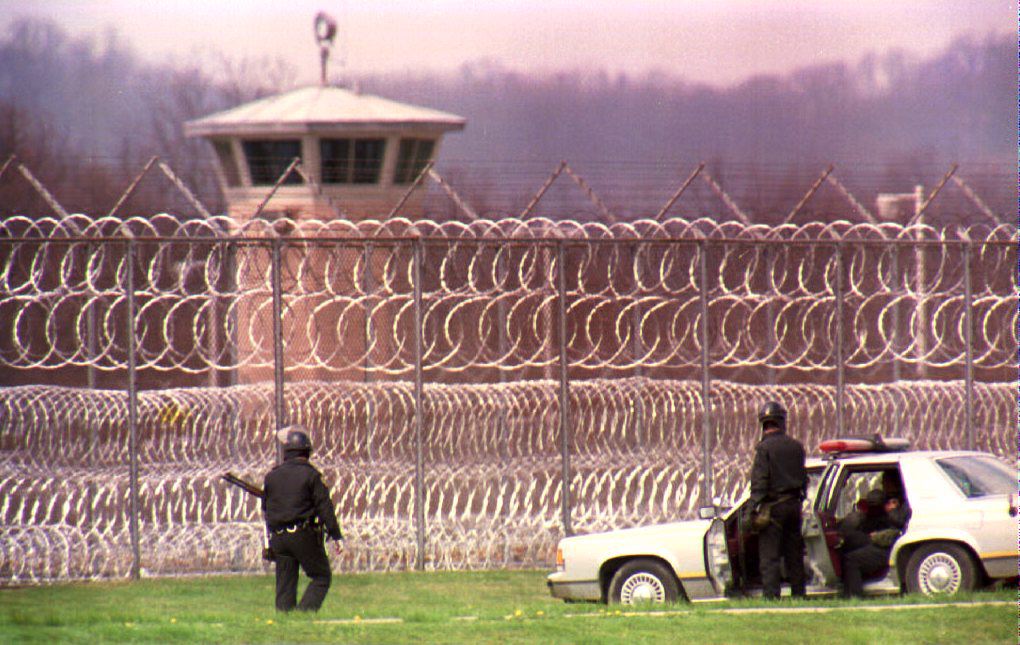

This month marks the 25th anniversary of the Lucasville Uprising, the longest prison revolt involving fatalities to occur in the history of the United States. Survivors of this 11-day prisoner takeover of the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility (SOCF) have been active and inspiring participants in the present movement for prisoners’ rights, gaining attention that was unavailable to them in 1993. In light of the growing momentum in prisoner uprisings, including the recent South Carolina prison riot that was the deadliest in the past 25 years, the Lucasville Uprising offers timely lessons on the interplay between repressive state forces and prisoner-led movements.

The Lucasville Uprising often gets lost in the retelling of prison rebellions because it occurred during the prison boom, a period of accelerating mass incarceration during which the widespread use of “three strikes” policies began, long-term solitary confinement grew into Supermax prisons, and prison construction and expansion skyrocketed.

Dan Berger and Toussaint Losier describe these years, from 1980 to 1998, in their new book Rethinking the American Prison Movement as a “largely bleak period for the prison movement … splintering the elements that had made [it] a potent force,” while prison rebels “found it more difficult to sustain the broad coalition that had been a key part of earlier phases of the movement.” Unlike Attica and other uprisings occurring during the civil rights era, or the present wave of prison strikes, the state’s narrative about Lucasville as a “dangerous riot” dominated coverage, overshadowing the political nature of the uprising and the prisoner’s legitimate grievances. Lucasville survivors continue to struggle against this shadow today.

The Takeover at Lucasville

The first wave of prisoner-led resistance actions occurred during the civil rights era of the 1960s and 1970s. The 1971 Attica Uprising is perhaps the most well-known of those rebellions, often remembered for the scale and sheer horror of its final day. After four days of protest, state and local police forces retook the prison, fatally shooting 29 prisoners and 10 guards and staffers while wounding more than 100.

The Lucasville Uprising came after the end of the civil rights era of prisoner resistance, when uprisings, occupations and sustained stand-offs with the authorities were common, yet before the contemporary prisoner-led movement that has emphasized coordinated actions across prisons.

The uprising resulted from the imposition of repressive policies in the facility, dubbed “Operation Shakedown” by SOCF Warden Arthur Tate. This series of changes encouraged snitching, saw forced rivals cell together, strictly enforced arbitrary rules and tolerated zero dissent or complaints. This turned SOCF into a powder keg of simmering violence. When a group of Muslim prisoners took a stand for their religious freedom, this powder keg exploded. Prisoners attacked guards, unlocked doors and expanded the protest into an entire cellblock occupation and hostage situation.

Eleven days later, nine prisoners and one guard had been killed, but prisoner leaders managed to get the state to accept to a list of 21 demands in exchange for a peaceful surrender rather than repeating the National Guard raid that caused so much bloodshed at Attica. Instead, the state’s revenge came after the surrender. Ohio indicted more than 40 prisoners, destroyed the bulk of physical evidence, and bribed or threatened some prisoners into testifying against those who led the negotiations, clearly violating the conditions of surrender they had agreed to. Five men were sentenced to death, and dozens more to long sentences — mostly on the basis of informant testimony, often before biased juries in communities that are economically dependent on prison jobs.

Ohio also overhauled its prison system and implemented highly controlled prison settings, a trend occurring throughout the US in the mid- and late-1990s. Officials advocated for the construction of Ohio State Penitentiary, a new Supermax prison outside of Youngstown, as a direct result of the Lucasville Uprising, where many of those convicted of uprising-related charges have now spent decades in solitary. In Ohio and elsewhere, prison regimes adopted long-term solitary confinement as a means to isolate prisoner leaders and quell any attempts at coordinated resistance.

Starting in 2010, prisoners disrupted that trend by organizing a resurgent wave of resistance actions across the US, despite their highly controlled environments, shutting down prisons and coordinating massive protests across Georgia, followed by California and Alabama, and then a nationwide strike on the 45th anniversary of the Attica Uprising on September 9, 2016. Since 2016, we’ve seen a continual increase in coordinated protests, uprisings and national calls to action that show no sign of stopping. A new era of prisoner resistance has begun, and the survivors of the Lucasville Uprising continue to play a major role.

Lucasville Survivors Continue to Resist

Less than a month after the 2010 work stoppages in Georgia, three Lucasville survivors on death row — Imam Siddique Hasan, Jason Robb and Keith LaMar — started a hunger strike at Ohio State Penitentiary to protest their convictions and the inhumane conditions of their incarceration. These three prisoners had each spent 19 years in solitary confinement at that point, with no human contact, no access to legal resources and few opportunities to communicate with each other or the outside world.

The 13-day hunger strike was remarkable because they won. They successfully leveraged media attention and support, including the backing of Staughton and Alice Lynd. These renowned activist-lawyers and historians helped prisoners sue the Ohio State Penitentiary years prior, filed appeals for George Skatzes, another Lucasville death row prisoner, and wrote a compelling history of Lucasville. At the time, the Lynds were also in communication with prisoners resisting solitary confinement at the Pelican Bay Secure Housing Unit (SHU) in California. Hearing of the solidarity both during the 1993 uprising, in the Georgia work-stoppage and in this successful Supermax hunger strike, a core group of Pelican Bay SHU prisoners were inspired to start the first California hunger strike six months later.

The Lucasville survivors continued to struggle, engaging in multiple hunger strikes between 2011 and 2016, consistently defending and expanding the concessions they’d won during the first hunger strike. Whenever a hunger strike or work stoppage occurred elsewhere, the Lucasville survivors and their outside supporters would discuss it and try to reach out to the participants. Imam Hasan encouraged his supporters to push for national coordination at every opportunity, often finding other prisoners who were talking about the same thing. In 2015, after connecting with Free Alabama Movement prisoners, outside support networks grew strong enough to make that coordination a reality. Prisoners chose September 9 as a national day of action and put the call together as rebellions and strikes in Alabama and Texas demonstrated their timeliness.

Media Attention

In contemporary prison rebellions, one of the oft-stated goals for prisoner organizers is to gain greater attention from the media, especially in mainstream outlets. Because prisons are purposefully hidden from public view, and the punishments inside obscured by administrators, prison rebels understand the virtues of employing a “strategy of visibility,” to highlight their grievances and/or demands, according to Dan Berger’s 2014 book, Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era. Imprisoned organizers use a variety of tactics to express their political voices and create alternative civic spaces to combat the extreme social and physical isolation embedded in current prison regimes.

“It starts with the people’s support,” Greg Curry, another Lucasville Uprising survivor, said over the phone, “and then the media amplifies the people’s support. I think the internet and the people’s support is the biggest thing, they allow us to be heard. And if not heard, at least allowed to be in a situation where we can’t be ignored.”

In the current wave of struggle, contraband cell phones and independent media have played major roles, allowing prisoners to release videos and statements depicting both the terrible conditions they endure and the acts of resistance in which they engage. Lacking this technology in 1993, Lucasville rebels had to use other innovative methods of communication.

The planned Muslim protest strategy at Lucasville was to barricade one cell pod and demand access to media outlets to air their grievances and bring more oversight from the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction’s (ODRC) central office. When this action spontaneously expanded to the taking of a full cellblock and nine hostages, the prisoners’ desire for media attention shifted from an objective of the protest to a defense tactic.

Recognizing that coverage would prevent the Ohio National Guard from coming in shooting, the prisoners tried to communicate with reporters directly. They hung sheets out of the windows, came into the yard with an enormous white flag and rigged up loudspeakers. The state responded first by using helicopters to cover the prisoners’ voices, then by cutting electricity and water to the occupied block. It wasn’t until the body of correctional officer Robert Vallandingham appeared on the yard that the state accepted negotiating with the prisoners.

Through negotiations and the one-by-one release of additional hostages, the Lucasville prisoners won access to a news reporter, who would enter the facility to take statements and describe the situation. Later, they would also negotiate access to public radio and television addresses. This process allowed the prisoners to both disseminate their 21 demands, many of which were that the ODRC simply follow its own rules. The negotiations additionally exposed the prison to several embarrassments, including one hostage guard converting to Islam during the uprising — a Black man who worked at this white-staffed, rural southern Ohio prison and who went on to publicly criticize the administration.

Unfortunately, these remarkable events didn’t gain much exposure from the media establishment, which remained largely unsympathetic to prisoners’ concerns and well-being. It wasn’t until D. Jones’s Shadow of Lucasville documentary film came out 20 years later that the uprising received the kind of multimedia exposure that our current media environment would have produced immediately. Instead, mid-’90s news outlets eagerly released unconfirmed reports of “bodies stacking up” in a bloody race war that prison authorities had expected, but that prisoner leaders actually mitigated. After the rebellion was over, this media establishment helped Ohio galvanize public outrage about the 10 deaths, particularly around the fatality of officer Vallandingham, creating a new spectacle to obscure the picture of SOCF that prisoner negotiators had exposed.

This experience helped Lucasville prisoners understand the complex relationship between mainstream, alternative and social media platforms, despite their decades of restricted access to most forms of media. Independent media coverage of the prison strike announcement and the concurrent actions in the South soon generated enough attention that mainstream media outlets were compelled to cover the story.

Since the 2016 nationally coordinated work stoppages, the alternative media landscape has grown and/or expanded to include more coverage of prison struggles and abolitionism. By strategically using these platforms, Lucasville survivors and others have been able to reach mainstream outlets even 25 years after the uprising to voice the injustices found in Ohio prisons and beyond. The more that prison rebels link their own struggles to different examples of oppression and resistance, the less able prison authorities are to dismiss or frame prison rebellions as anomalies.

Negotiating Demands

Prisoner-led movements are often faced with the challenge of issuing demands and holding the authorities to concessions. In Lucasville, the prisoners negotiated through the fences during the standoff, with the help of trusted civil rights attorney Niki Schwartz. They got the state to accept a 21-point agreement to reform the system and peacefully conclude the uprising — an agreement that prison authorities promptly violated, eroding their credibility and any motivation for peaceful resolutions to future disturbances. Upset by how he was manipulated by the state and the injustices faced by the prisoner survivors, Schwartz continues to advocate for them to this day.

Negotiation with unreliable and dishonest prison officials continues to obstruct progress of the prisoner-led movement today. In 2011, California strikers in Pelican Bay ended their first hunger strike when the state promised reform and conceded a few minor demands as a gesture of good faith. Prisoners had to resume and expand the strike repeatedly over the next two years because prison officials didn’t follow through, eventually leading to the 30,000 participant rolling hunger strike from July to September of 2013. Two people died on hunger strike, pressuring California prison officials’ to fulfill their promises. The much larger and longer wave of hunger strikes ended not with concessions by the prison authorities, but with the prisoners winning a lawsuit. The limited gains of this lawsuit were significantly eroded within the first year.

Lucasville prisoners found themselves in a similar situation in 2013. Hasan, LaMar, Robb and Curry went on a hunger strike demanding access to on-camera interviews with media in coordination with the 20th anniversary Re-Examining Lucasville Conference. When the ACLU offered to file a lawsuit, the prisoners, like those in California, ended their hunger strike, moving their protest into the courts. The ACLU has backed out of the case after further review, but independent pro-bono attorneys continue to pursue it.

In Ohio, California and elsewhere, prisoners continue to struggle with a lack of good options when their reasonable humanitarian demands are stonewalled by prison officials. From 2011 to the present day, Lucasville prisoners have adopted a long view of struggle. By using numerous hunger strikes and rallying committed support, they’ve gained concessions from officials in writing, which they must defend through persistent daily interactions with staff. These imprisoned rebels have charted a course to attain gradual and progressive victories, which connects them with humanity, but they have yet to win anything like justice or basic human rights.

In a phone call with the Truthout, Robb describes this process as a long fight to assert prisoners’ basic humanity:

For people to actually see us for who we really are, and us being ourselves … that’s the power. Take away that stigma and disinformation … because we’ve been able to do that, [we have] changed things. I understand why it’s frustrating. It’s aggravating. You have to be comfortable with who you are and realize what you are able to live with and not live with. … Are you willing to die to be treated like a human being? I am. In a heartbeat. By any means.

State Retaliation

As described above, the state of Ohio broke the peace agreement and went after negotiators. While Schwartz recruited the best possible lawyers, the state used underhanded means to remove them. Informants were recruited and Anthony Lavelle, the prisoner Staughton Lynd believes was most likely to have actually killed the guard, testified against the other prisoner leaders. This is how prosecutors secured their death penalty convictions despite, as prosecutor Daniel Hogan later admitted in an interview with D. Jones, that we may never “know who hands-on killed the Corrections Officer Vallandingham.” There is a massive amount of carefully presented evidence to suggest the re-opening of these cases.

For example, despite faulty informant testimony and manufactured evidence against death row Lucasville prisoner Keith LaMar, the courts denied him the same access to re-examine evidence that had been granted other Lucasville defendants, and rejected his appeal in the midst of the 2011 hunger strike. LaMar’s words about the strike were being published online nationally at the time, leading supporters to suspect the decision was a form of retaliation. In a later hearing, a judge said LaMar’s claim that the evidence against him was provided by informants who were coached and bribed with extra privileges was “meritless.”

Hasan and the prisoner negotiators were careful to protect themselves. In a personal correspondence, Hasan said,

We know that throughout the history of prisoner uprisings, the prison authorities get very upset. They become very vindictive and they throw their own playbook out of the window. … The prison authorities want to become the judge, the jury and the executioner themselves. So they jump on people, they kill people, they come up with excuses and they try to make false justifications as to why prisoners are injured. So we wanted religious leaders and the media to witness it so that we did not have to worry about being assaulted during the initial stages of surrender. In addition to that, we wanted people to be given medical treatment, because then you would have photos of how people were, most of them didn’t have their faces busted or severe injuries. So if something happened to them after the fact, then it would be safe to say it was a result of retaliation.

Curry, Lamar and the hundreds of prisoners who surrendered on the yard the first night of the uprising had a different experience, even though they were outside when the uprising started. “We were ordered to line up and march into K-block’s gym,” LaMar describes in his book Condemned, “Where we were stripped naked and forced, with our hands now fastened behind our backs, to sit on the cold floor like animals.” Later they were moved in groups of 10, still naked, into cells designed for one person and deprived of food for at least 24 hours. In that cell, William Bowling killed Dennis Weaver in a fight over sandwiches when food was finally delivered. LaMar’s non-cooperation with investigators about this murder is what led to his targeting by prosecutors and death penalty conviction before an all-white jury.

Like LaMar, Curry was on the yard when the uprising started and surrendered the first night, but having refused to cooperate with investigators, he was likewise targeted. At a trial full of informant testimony and outright lies by prosecutors, the jury gave him life without parole instead of the death penalty. So guards set out to finish what the prosecutors were unable to do, promptly attacking Curry with harassment and confinement in a “sweatbox” cell with no ventilation, food or air conditioning for an extended period of time. Curry attributes this retaliation to the state’s desire to obliterate any sign of rebellion.

Lessons of Violence

Lucasville teaches us to expect the criminal legal system to work hand-in-hand with correctional officers’ drive for revenge against prison rebels. Laws exist for purposes entirely unrelated to justice, and the utmost attention must be paid to the aftermath of any prisoner resistance action. For example, 16 prisoners were indicted for the single murder at Vaughn Correctional Center after the brief takeover in February 2017.

Nowadays, Hasan and Jason stress the use of nonviolent tactics, hoping that appearing sympathetic to liberal publics will protect prisoner rebels from retaliation, but this hasn’t always proven to be true. Nonviolent marchers at Kinross Correctional Facility in Michigan report being hit with tear gas canisters point blank and hogtied in the rain for hours after their September 9 demonstration. Cesar DeLeon and LaRon McKinley were force-fed for more than seven months to break their hunger strike in Wisconsin. Kelvin Stevenson was nearly beaten to death with a hammer for participation in the nonviolent Georgia work stoppage. Countless other prisoners across the country have been transferred to the torture of long-term solitary confinement, deprived of food and harassed in forms more diverse than we can recount here. These are just the stories that escape correctional facilities and public records embargoes.

The survivors of Lucasville recognize that what matters most is the court of public opinion, which compels them to struggle for access to media, public support and widespread attention. Organizations such as the Anarchist Black Cross and the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee exist to support prisoners facing repression, amplify prisoners’ voices and get their stories to the media. By building networks of support that focus on challenging state repression behind bars, supporters can help buffer against retaliation and reduce the legal consequences that prisoners face by participating in the movement.

These efforts at outside support are essential both to counter dominant prison narratives that demonize prisoners and to protect and encourage further resistance. In Imam Hasan’s words,

The fear that the prison authorities [put] into prisoners is preventing them from standing up and rising up to bring about corrective changes. Some people don’t want to get involved because they understand the retaliation…. They might get abused, assaulted, beat with hammers, choked out, some prisoners get choked to death — many things might happen. [For us,] the shift came about because people had the utmost respect for those involved in Lucasville, [knowing] we were ready to stand up and to take the necessary chances to bring about revolutionary changes. Lucasville rocked the state of Ohio, [causing] people throughout the state to take a serious look at the kinds of deprivations that prisoners are experiencing.

To contact the Lucasville survivors:

Keith Lamar #317-117

Jason Robb #308-919

Siddique Abdullah Hasan # R 130-559

Greg Curry # 213-159

OSP

878 Coitvsille Hubbard Road

Youngstown, OH 44505

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.