This weekend, the women and children who'd spent 17 months living on the sidewalk outside Oaxaca's governor's palace set off for home. In the spring of 2010, these refugees fled their town, San Juan Copala, the ceremonial center of the Triqui people, abandoning homes where their families had lived for generations. Many houses were burned after they left.

Stringing tarps and ropes across the palacio's outdoor colonnade, they set up their planton, an impromptu community of sleeping and cooking areas across the sidewalk from the zocalo, the plaza at Oaxaca's heart.It looked hauntingly similar to the settlements of the Occupy protesters that spread across the United States last fall, but rather than fighting to remain in their tents, the Triqui families in the planton were fighting for the right not to live there, for the right to go home.

Last December, they announced an agreement with representatives of Gabino Cue, elected governor last July, in which the state promised to protect the families if they returned to San Juan Copala. The families waited a month, and then last week set out from Oaxaca's capital city to San Juan Copala, about eight hours away. When their caravan reached the Triqui region, however, just outside the tiny hamlet of Yosoyuxi, a police cordon blocked the road, preventing their further advance.

While the women and children stood on the blockaded highway, chanting and singing, their leaders met with state government representatives in the nearby city of Tlaxiaco. Government Secretary Jesus Martinez Alvarez prevailed on leaders of the caravan to halt their progress, and send ten delegates to a community meeting held Sunday in San Juan Copala. The displaced families vow they intend to return nevertheless, and accuse the state government of detaining a caravan member, David Venegas.

Martinez Alvarez proposes that the return be delayed another two weeks, while, he says, the needs of Copala residents are met, such as health, education and social development, which he held were the underlying cause of violence in the area. But the families have been left in the middle of the highway, in the same place where a notorious attack occurred on another similar caravan two years ago.

Violence is still a fact of life throughout the Triqui region. Many question whether the families really can go back safely. Even more important, they ask what can bring an end to that violence, after costing the lives of at least 500 people over the last two decades.

This question is not just debated at the blockade in the highway, on the sidewalk by the zocalo or in Oaxaca only. It is asked, albeit in whispers, by migrant farm workers in Baja California and Sinaloa, in northern Mexico, and in Hollister and Greenfield, in California's Salinas Valley.

Mixtecos have been leaving Oaxaca for decades, driven mostly by the endemic poverty of the Mexican countryside, says Gaspar Rivera Salgado, a Mixteco professor at University of California, Los Angeles, and past coordinator of the Binational Front of Indigenous Organizations. Yet, for many years, the Triquis, who were equally poor and live in the same region, stayed put. Their migration only began when the violence in their communities made life unbearable.

Once displaced, they began to migrate within the Mixteca region, then within Oaxaca and then within Mexico. They traveled north, following other Oaxacans to San Quintin in the 1980s, and then in the 1990s, to California.

Triqui migrants might have escaped the violence, but not the political presence of the groups they were fleeing. Wherever they went, the Movement for the Unification of the Triqui Struggle (MULT) and the Social Welfare Group of the Triqui Region (UBISORT) sent agents, requiring people to pay monetary quotas and participate in mobilizations.

In the 1980s, Triqui activists organized MULT. “It was a grassroots organization to fight the caciques (rural political bosses) over control of land, forests and other natural resources,” says Rivera Salgado. “The caciques were so violent that MULT members had to arm themselves. Eventually, those armed men became a paramilitary group. The caciques were overcome, but what began as a grassroots organization became something different. There was no transition to a civil society form of organization.”

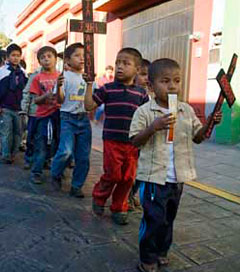

A Triqui boy carries a sign that says, “We want justice for the widows, the orphans and our injured. (Photo: David Bacon)

Eventually MULT itself fractured into factions. One faction became UBISORT, which began fighting MULT for political control of Triqui communities. Oaxaca's repressive state government used the conflict to enhance its own control.

UBISORT was organized with the support of then-Gov. Jose Murat, and became a political support base for Oaxaca's old governing party, the PRI (Party of the Institutionalized Revolution). MULT organized its own political party, the Popular Unity Party. But behind the parties were the guns.

“A civil war went on between them,” Rivera Salgado says. In 2006, Raul Marcial Perez, a leader of UBISORT, was assassinated. Then in October 2010, Heriberto Pazos, the founder of MULT, was gunned down in the streets of Oaxaca city.

In the only municipio that remained in Triqui hands, San Martin Itunyoso, Antonio Jacinto López Martínez, a MULT leader, was elected president in 2004, but then couldn't take office because of threats and fled to the nearby city of Tlaxiaco. Last October, as he was crossing the street there with two members of his family, a gunman shot him in the head. Many others were killed in years of violence and retribution.

The Triquis attempted to create an autonomous town in San Juan Copala, and were expelled by paramilitary gangs. They carried crosses with the names of people who were killed.(Photo: David Bacon)

The High Cost of Migration

For Triquis, migration has had a high cost – they've had to fight for survival wherever they went. “They faced tremendous racism and prejudice,” Rivera Salgado charges. “They're always the outsiders, treated like savages.”

Over the course of some 25 years, so many have fled the political murders plaguing their homeland that they've formed towns like Nueva Colonia Triqui, or New Triqui Town, in Baja's San Quintin Valley. In that colonia, or in California's Triqui neighborhoods, people ask whether peace is possible, and, if it were, would they go home, too?

“People left looking for a better future, but they worry about the safety of their families at home,” says activist Elvira Santos (whose name has been changed), pointing to the fear that many Triquis share of reprisals for speaking publicly not only against themselves, but also against their families in Oaxaca. “They'll think twice before going back because the conflicts and the same armed groups are still there.”

In north Mexico, migrants found farm labor camps with dirt floors and no electricity. When they wanted homes for children and families, Triquis and other indigenous migrants had to mount land invasions, building houses on federal land and then awaiting the police sent to evict them.

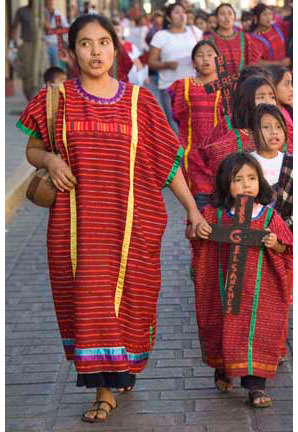

The march called on Gov. Gabino Cue to guarantee their safety when they try to return to the town and to arrest those responsible for the killings.(Photo: David Bacon)

In one of the most celebrated cases, Julio Sandoval, a Triqui leader from Yosoyuxi, was imprisoned for two years in the penitentiary in Ensenada for helping families settle in Cañon Buenavista.

When Triqui migrant farm workers arrived in Greenfield, the local police and legal system condemned them for cultural practices like home births or early marriages, or for drinking in public, a normal activity at home. Eventually, they reached agreement with the local police chief, who even set up a desk in the police station for a Triqui leader to provide translation.

Then town residents, who saw the migrants as unwelcome invaders, tried to fire the chief. The Triqui community by then numbered at least 3,000 people. Helped by the United Farm Workers, migrants marched through town to assert their right to live there.

Roots of the Violence

Adelfo Regino Montes, a Mixe indigenous leader and writer for Mexico's left-wing daily, La Jornada, traces the violence in the Triqui region to “political submission, territorial disintegration, economic exploitation, racial discrimination and exclusion in every aspect of daily life.”

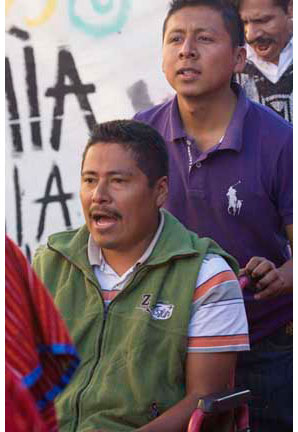

Triqui men joined the women and children in the march. (Photo: David Bacon)

After Mexico won its independence, Triquis controlled three municipios, or counties, where they were the majority. That gave them some degree of political power. After the Mexican Revolution, however, two of the municipios were dissolved, and much of the community's autonomy was lost.

“San Juan Copala itself was no longer a municipio,” Santos explains. “Many mestizos [people of mixed indigenous and Spanish ancestry] didn't want Triquis to have power. They introduced alcohol and arms in order to gain control of the land and resources.” Those caciques ruled Triqui towns using repression and violence.

“[Triqui municipios] were dispersed into districts where non-indigenous people are the majority,” Regino Montes said in a 2010 Jornada column. “The big majority of Triqui communities have been excluded from any decisions that affect their lives and destinies, undermining their autonomy and freedom to make their own choices. Those decisions remained in the hands of the caciques, the state and federal governments, and the party leaders of the PRI.”

The women carry a banner that says, “Neither forgive nor forget, punishment to the assassins. Autonomous town of San Juan Copala.” (Photo: David Bacon)

“The violence is created by a lack of the assertion of the rule of law. But the government has excused its failure to stop it with such racist ideas as 'Triquis are savages and uncivilized,'” Rivera Salgado charges.

Indigenous Self-Government

Looking for a way out themselves, in 2007, Triqui activists created the autonomous municipio of San Juan Copala, inspired by the experiences of the Zapatistas in nearby Chiapas. “They recreated the system of indigenous self-government,” Regino Montes wrote, “the only real possibility for peace in the region.”

“They were looking for a political alternative,” adds Rivera Salgado, “and they used the political process. They weren't armed. And they won in a clean election.”

Those activists had roots in another splinter from MULT, called MULT Independiente, or MULT-I. UBISORT and MULT united against them, and eventually laid siege to the town, which went on for months. A number of residents were killed.

A Triqui girl carries a sign that says, “Long live the autonomy of the native people of the planet earth.” (Photo: David Bacon)

On April 27, 2010, a caravan of Mexican and European human rights activists set out for San Juan Copala. They were stopped at a roadblock, and gunmen began shooting. Beatriz Alberta Cariño Trujillo, a Mexican human rights activist, and a Finnish supporter, Tyri Antero Jaakkola, were murdered. The others fled into the hills.

Human rights lawyer Gabriela Jimenez Rodriguez said she was captured by hooded men who told her they were from UBISORT and MULT. “They told us than no one could pass here, that it was their territory.” Finally she and others were released. Police recovered the two bodies, but never tried to enter the town.

On August 22, three more people were killed and two wounded as they drove to nearby Santa Cruz Tilapia, where residents were also trying to establish an autonomous municipio. One was the town leader, Antonio Ramirez Lopez, 78 years old.

Then in September, 500 paramilitaries surrounded San Juan Copala and told supporters of the autonomous municipio they had 24 hours to leave. “That wasn't just a threat,” Reyna Martinez, one of the town's leaders, told La Jornada. “They did the same thing in San Miguel Copala, where they killed twelve of our colleagues in the city hall. Neither state nor Federal authorities dare even to come into San Juan Copala.”

Women and children walked past the street vendors selling toys in the city's main plaza, with the star and masked figure on their banner showing their connection to the Zapatista movement. (Photo: David Bacon)

No Need for Protective Measures?

Oaxaca's governor at the time, Ulisses Ruiz, notorious for his violent suppression of the teachers' strike of 2006, said there were no gunmen, deaths or disappearances in the Triqui region, and no need for protective measures for residents. By that time, families who'd fled were already living in the planton outside his office, and some had gone to Mexico City to set up a similar planton there. “They got us to leave,” said another leader, Marcos Albino Ortiz, “but that doesn't mean we've given up.”

Last July, however, Gabino Cue, who Ruiz defeated in the election of 2004, beat the PRI candidate for governor. UBISORT campaigned for the PRI. MULT's PUP ran its own candidate, viewed largely as an attempt to draw votes from Cue. After the election, Cue put Region Montes in charge of the state Secretariat of Indigenous Affairs. Rufino Dominguez, former coordinator for the Frente Indigena de Organizaciones Binacionales, was appointed director of the Oaxacan Institute for Attention to Migrants.

The women in the planton didn't stop demonstrating against the government, however, and the violence continued. In August, three MULTI members were killed in Agua Fria. Their bodies were brought to the planton for a public funeral. In October, Reyna Martinez was arrested with two dozen others for occupying a piece of land near the airport, in an act of civil disobedience. They demanded that the new state government provide protection to allow their return to San Juan Copala, pay for the destruction of peoples' homes there and arrest those responsible for the killings. And in December, women and children in bright, red huipils marched through Oaxaca city, demanding the government accept the conditions.

In response to the pressure, Rufino Juarez, a UBISORT leader, was arrested in May for killing MULTI activist Celestino Hernandez Cruz a year earlier. Cue's administration then issued arrest orders for a number of others, but so far none have been detained, with one exception. Authorities did arrest a MULTI founder and retired teacher, Miguel Angel Velasco, accusing him of arranging the disappearance of two young women from MULT in 2007.

The planton in front of the governor's palace on the main square in Oaxaca. (Photo: David Bacon)

Nevertheless, Marcos Albino Ortiz, says that the state government “has fulfilled about half of what it agreed to. We're going back to San Juan Copala, and we're talking with the communities there to ensure they support our decision. Our objective is to pacify the region.” He predicts that the state and federal police will provide an escort, along with representatives of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which has issued orders of protection for many of the activists. Some 135 families have received some restitution for their burned homes, he says.

Can Triquis Go Home?

To ensure peace in San Juan Copala, however, some police presence there is unavoidable, at least in the short run, Rivera Salgado believes. “The litmus test is whether the government will create the conditions in which people can go home,” he says. “You can't change overnight a situation that's existed for 30 years. In the short term, they have to disarm the armed people. This can create political space. But military occupation is not a long-term solution. People need to become a force for change themselves.”

Following the ambush of the caravan, Regino Montes asserted, “The solution must be the recognition and respect, in law and in action, for the process of Triqui autonomy.” Now, he is a responsible official in a government that has the power to implement that recommendation.

Peace in Oaxaca may encourage Triqui migrants to return, but going home won't be easy. No one can afford to go back to Oaxaca just to take a look.

A child sleeps in a planton set up by the Triquis in Mexico City's zocalo, or main square. (Photo: David Bacon)

Triqui migration hit the US after the amnesty of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, so most people have no legal immigration status. They can cross the border into Mexico, but coming back to the US is a much bigger problem. It's expensive – $2,500 for a coyote for the crossing is two months wages for a farm worker. Plus, it's more dangerous every year, as people get pushed by increased enforcement into the most remote sections of the border to cross.

Going back home is a permanent decision, not a temporary visit. Nor has the fear of violence there diminished. In the last few years, five Triqui families even won political asylum, helped by San Francisco's Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights. Nevertheless, “most migrants get much harsher treatment now,” according to Rivera Salgado. “The current enforcement policy is based on excluding them, through violence and jail at the border, and isolation and fear in their community. The idea is to make life so hard for them in the US they'll have to leave. But where are they supposed to go?”

“I think a lot of people would go home if they could,” Santos believes. “Our land is very productive, and as farm workers here we've seen new crops that we could grow in Oaxaca. But we need jobs and schools there, and especially security. Right now, we don't know if we can even hope for that. Some of us have lost hope. Our governments have made these promises before. It would be good if it were true this time, but we have to see if their actions match their words.”

“And where is home?” asks Rivera Salgado. “Lots of Triquis have grown up in San Quintin or Greenfield by now. Yet the first generation still yearns for connection to San Juan Copala. It is part of their identity and sense of belonging. Everybody needs that.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $29,000 in the next 36 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.