The battle for the British-controlled Falkland Islands off the coast of Argentina continues to kill, even 30 years after Argentine troops landed there on April 2, 1982. The struggle for a group of windblown islands in the South Atlantic has claimed more lives since the fighting ended than when battle raged. SAMA – the South Atlantic Medal Association, which represents and helps Falklands veterans in Britain – says that at least 264 veterans of the Falklands have now taken their own lives. This contrasts with the 255 who died in active service.

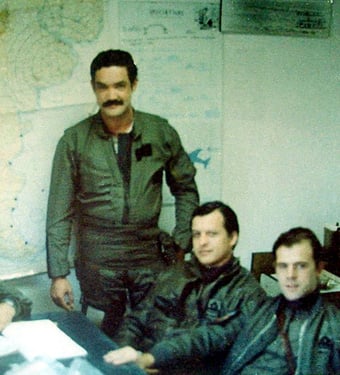

In Argentina, the battle for the Malvinas, as the Argentines call the Falklands, has taken an even higher toll. Much like their US counterparts home from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars – who, in 2010 and 2011, lost more of their lives to suicide than to combat – it is almost certain that more Argentine veterans have taken their own lives than were killed in the Falklands war, according to Peniel Villarreal, a member of the Federation of War Veterans of Argentina. I met with Villarreal and other veterans in a run-down Buenos Aires suburb in 2009.

It is difficult to confirm an exact number because of the shame involved in suicide, and many of the deaths have been disguised as accidents.

Argentina’s military regime mistakenly counted on the United States to support its 149-year-old claim to the British territory. The defeat marked the beginning of the end for the Argentine junta, and a democratic government was elected in 1983.

This small war had other major consequences. It ensured two election victories for Margaret Thatcher, discredited military rule not just in Argentina, but across South America and ushered in an age of democracy in Argentina.

In the 74-day war, 255 British and 649 Argentine soldiers, sailors and airmen, and three civilian Falklanders were killed.

But at least 400 Argentine Falkland veterans have taken their own lives since then, highlighting the tormented plight of those who came back defeated to a country that wanted to forget. This figure represents only confirmed suicides.

“When we returned, we were ignored,” said Villarreal. “We were nobodies. Nobody wanted to talk to us, give us health care or jobs. We came back from a campaign where our friends were killed to a country that viewed us as letting them down. That’s why more than 400 of our colleagues have taken their own lives.”

The veterans call it a forgotten war, not because of the lapse of time, but simply because no one wanted to remember.

“We were told to stay silent,” said Santiago Tettamanzi, an officer on the Caracarana, a merchant supply ship that was attacked off Port King. “Coming back as a defeated army is so different than coming back as a victorious one.”

The military junta ordered them not to speak about their experiences, and the veterans went quietly back to their homes and struggled to rebuild their lives.

“Make no mistake, at first we were proud and even happy to be called on to serve,” Enrique Lewton said.

“The Malvinas are Argentine land, and we believed we were fighting colonialism. But as soon as we landed, we knew we were unprepared. It was freezing, we did not have adequate clothing, some even wore sandals. The equipment was not up to standard. We shivered in the trenches. And originally, we believed that all we had to do was land and then the diplomats would sort it out. But we soon realized we had to fight.”

The Federation of War Veterans of Argentina has 12,000 members and is now fighting on another front, for social benefits.

“About 10,000 troops landed on the Malvinas but, in total, there were about 22,000 troops and civilians involved in the war effort. Of those involved, we represent about half. Many do not want to join because the memories are too painful,” Villarreal said.

“We managed to increase the pension from 550 pesos (about $125 US) to 3,000 (about $680 US) pesos monthly. But we also need adequate health care.”

Even though the spotlight is back on the islands, the plight of the veterans is not likely to improve dramatically. Argentina has slashed military spending across the board since the Malvinas campaign. Its air force, for example, has changed little since 1982. There have been rumblings from non-war veterans, those who entered the armed forces after the Malvinas campaign and are now approaching retirement, that their pensions do not even match the paltry ones given to those who fought in 1982.

Those who answered the call and were sent to fight with substandard equipment are struggling to have their voices heard.

“We are trying to get in touch and bring in more members as the suicide rate shows many veterans still have great difficulty coming to terms with the trauma. This is a huge country and it can be logistically difficult to get in touch with people, but they need our support,”

Many of the suicides have been recorded in the remote provinces of Chacos and Corrientes in the north of the country, where conscripts had never even laid eyes on the sea or snow before being sent to the Falklands. In 1982, Argentina could conscript citizens for military service – one year for the army and two for the navy.

The veterans interviewed for this story say they harbor no feeling of bitterness towards the British or Britain.

They realize they were used in a catastrophic gamble by a despised military junta, but they all passionately believe the islands are Argentinian. All agree on the professionalism of the British army, especially in their treatment of prisoners.

“We were treated well by the British,” Villarreal said as others nodded their heads in agreement.

“I was injured when a mortar landed on my foot in the battle for Goose Green. It blew away my companion’s legs, and I thought I was dead. I was taken to a hospital ship, the Uganda, where I begged them not to kill me.”

Smiling, Villareal remembers the doctor’s words exactly: “‘I am here to cure you, not to kill you.’ He did; he saved my foot.”

Years later, a friend of Villarreal met the doctor who treated him at a trauma medical course in the United States. The doctor came to Argentina to meet his former patient.

“It was an emotional moment. His name was Michael Jones, and he asked me how the leg was. I said, ‘Fine.’ I owe him my life.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $22,000 by the end of today. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.