I’ve been fond of quoting the late economist Charles Kindleberger, my old teacher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who used to say that anyone who spends too much time thinking about international money goes mad.

But I’m thinking that we need to expand the proposition: it seems that almost everyone who weighs in on monetary matters of any kind goes crazy.

Those who expected more traction on the United States’ economy from the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing program are disappointed, but the proper reaction is, “Meh.” Just not a big deal. Similarly for the depreciation of the dollar from its crisis peak to more or less where it was in early 2008 (which has some people hysterical).

The whole tone of this discussion is reminiscent of the way people talked about the gold standard back when it was widely thought that any meddling with the sacred role of a metal with precisely 79 protons would mean the demise of civilization. But it has been 80 years since Britain went off gold, and last I noticed, William and Kate weren’t getting married in a desolate wasteland. We’ve had freely floating exchange rates for almost 40 years, right through the reigns of Saint Reagan and Dear Leader (and no, Sept. 11 had nothing to do with the decline of the dollar under George W. Bush — like I said, something about this subject brings out the crazies).

Anyway, money and monetary policy are basically technical issues, albeit important ones. The fate of Western society is not at stake, nor is there a deep moral issue in allowing the purchasing power of the medium of exchange to depreciate modestly over time.

Calm down, everyone.

Speaking of International Money …

No sooner do I suggest that the craziness associated with discussions of international money has now shifted to money in general than I see Steve Pearlstein writing a column for The Washington Post about global economics that I agree with halfway through, but that veers off into a misplaced focus on the international role of the dollar as the key concern.

Mr. Pearlstein, in an article published April 22, says there are two ways the dollar story can play out. “In the optimistic scenario, a credible budget deal is reached in Washington, the Fed manages to sop up all the excess liquidity it has created, and the long-term slide in the dollar remains gradual enough for the world to muddle through until a new order and a new architecture can emerge,” he writes. “In the darker scenario, hinted at last week by the leading credit-rating agency, the failure to adopt a budget deal triggers a U.S. credit crisis that spawns a dollar crisis, which sets off another global financial crisis — one that makes the last one look like child’s play.”

Now, Mr. Pearlstein isn’t crazy the way the goldbugs are — but he does seem to share the common tendency to exaggerate the importance of owning a global currency.

What does the United States gain from the dollar’s special status? One clear gain is that foreigners are holding a lot of pieces of green paper with dead presidents on them — maybe $500 billion worth. That’s in effect a zero-interest loan; in normal times, when short-term interest rates are 4 or 5 percent, it’s worth something like $25 billion a year.

Nice, but not a big deal in a $15 trillion economy.

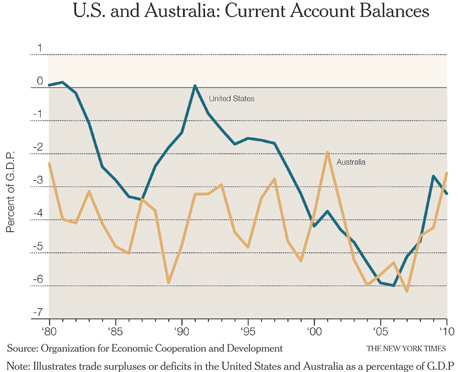

Then come the more dubious parts. It’s often asserted that it’s only because of the dollar’s special status that the United States can run persistent trade deficits. But that’s just not true: other countries whose currencies have no special role can do the same, and have (as the chart on this page shows).

Still, it could be that purchases of Treasury bonds by foreign central banks keep the dollar stronger and interest rates lower than they would otherwise be.

The way to think about this is that Chinese reserve accumulation, for example, is a sterilized intervention in the dollar (one that isn’t allowed to affect the money supply).

In general, we tend to think that sterilized intervention is only modestly effective, because it tends to be offset by private capital moving the other way. But maybe there’s something there.

It’s really hard, though, to see how the benefits of the dollar’s reserve status could be more than a fraction of a percent of gross domestic product.

It’s not a trivial issue, but it’s not among the things that should be key drivers of economic concern.

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Paul Krugman joined The New York Times in 1999 as a columnist on the Op-Ed page and continues as a professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 2008.

Mr Krugman is the author or editor of 20 books and more than 200 papers in professional journals and edited volumes, including “The Return of Depression Economics” (2008) and “The Conscience of a Liberal” (2007). Copyright 2011 The New York Times.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.