“Dirty Energy is a powerful wake-up call, showcasing the dangers of offshore drilling, the lackadaisical response of the industry to potential environmental and health crises and the inevitable result of government pandering to corporate donors.”

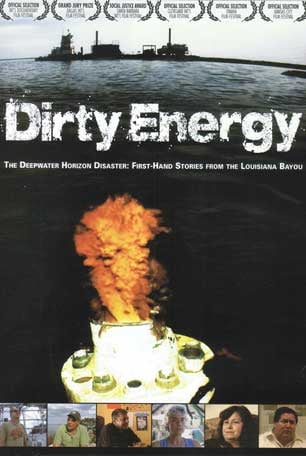

Dean Blanchard, owner of the largest shrimp business in Grand Isle, Louisiana, is hardly reticent when it comes to British Petroleum, the company whose Deepwater Horizon Oil rig exploded off the Gulf of Mexico on April 20, 2010. “BP stands for Bad People,” he tells the producers of Dirty Energy: The Deepwater Horizon Disaster, First-Hand Stories From the Louisiana Bayou.

Blanchard is one of the many outspoken Bayou residents who are interviewed in the film, all of them lamenting the losses they experienced in the aftermath of the largest environmental “accident” in US history. To a one, they are critical not only of BP – a company that had long sidestepped safety to enhance profit – but of government capitulation to the corporate giant.

While the movie addresses what government should have done – and still could do – the 94-minute documentary focuses on the personal impact of the explosion on shrimpers, people who fish, and local residents. Not surprisingly, it is heartbreaking.

Archival footage is also woven in so that we can once again see BP head Tony Hayward stoically promise “to make this right” and hear members of Congress question the corporate execs Congress ultimately let off the hook. Still, it is the regular folks who pack the biggest punch. Betty Doud, for one, moved to the Gulf decades back because she “fell in love with this little piece of paradise.” Today, she reports that she no longer sees the area’s beauty. “There is no life on the beach,” she begins. “The shells, hermit crabs, they’re all gone. You don’t see fish jumping anymore. They’re dead. They killed it.”

Margaret and Kevin Curole grew up shrimping and say that they wanted their kids to know how to live off the land. “You’d catch it, clean it and eat it. It was awesome,” Margaret reminisces. “We lived free, with fresh fish every day. We ate like kings and queens.” What’s more, she continues, she and her community were self-sufficient. “We always prided ourselves on never taking help, but we became dependent on someone else to clean up the mess.” Having to rely on others has taken a toll, she adds. “This is the first time in my life I’ve heard defeat in people’s voices.”

“Every year around July 4th, crabs would show up on the beaches, so big you could scoop them up,” Kevin says. After the spill, he worked on a clean-up crew and saw the impact not only of the oil, but of the dispersant, Corexit, on the local ecology. “The crabs did not show up. Dolphins and sperm whales died. Sea turtles breathe the oil and chemicals and it knocks them out, so they drown,” he says.

Dr. John Lopez, Director of Coastal Sustainability for the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation, is particularly critical of the dispersant and notes that it creates dead zones that kill marine life – including fish eggs and larvae. “Anything that swims into the toxic zone will likely die,” he says.

And it is not just marine life that suffers. Kevin Curole says that while working on a clean-up crew, he became so ill that he was unable to get out of bed for several days. “My respiratory system was overtaken from being in the mess,” he reports. “BP sent us out there. We had no protective gear,” so workers did not cover their eyes, hands, noses or mouths in the scramble to clear the debris as quickly as possible. It’s a shocking revelation and Dirty Energy is filled with other shocking moments and disturbing footage. In one particularly noteworthy scene, the film tells viewers that companies are supposed to inform the Environmental Protection Agency about any illnesses, save for colds and the flu, that occur during a clean-up effort. The problem? According to community organizer Kindra Arnesen, the symptoms of chemical poisoning mimic the symptoms of – you guessed it – cold and flu.

What’s more, the film informs us that people in the Gulf eat approximately 12 times the amount of seafood as people in the rest of the country. Will they become sick somewhere down the line? Probably, but it will be impossible to prove that their illnesses came from toxins in the water and not something else.

“I’d rather be dead than not eat seafood,” Dean Blanchard says. “I’m not gonna stop.”

Self-injurious? Maybe, but the likely loss of a way of life that has been passed down for generations – living off the land as the Curoles once did – is nonetheless something to mourn, especially since the explosion could have been prevented had more attention been paid to safety.

Few know that as well as marine toxicologist Riki Ott. Ott lived in Alaska in 1989 when the Exxon Valdez oil spill occurred, so she knows there are no quick fixes to repair contaminated oceans and beaches. At the same time, she says that companies like Exxon and BP did not see the Valdez spill as a call to action and hired top-of-the-line advertising firms to do damage control instead of making their operations safer for workers. “The industry learned to control what images are seen,” she says. “The carcasses [that turn up on the sand] are whisked away so it becomes difficult to prove what really happened. If people are made to believe that oil and tar are gone and the seafood is safe, BP is off the hook and unaccountable.” Could this be why, as the film suggests, BP spends just .0033 percent of its revenue on the development of safety protocols and protections?

Nearly three years after the BP explosion, the Gulf region is no longer on the nightly news. Indeed, it’s more likely that the evening newscast will be interrupted by self-promoting BP ads touting the company’s alleged commitment to community-building, clean energy and research. Residents of the Gulf know better than to trust what BP tells them, but they also know the problems run deeper than one company’s malfeasance. “Until we get rid of lobbying, big oil is gonna run things,” concludes Karen Mayer Hopkins, a commercial seafood buyer-turned-community activist. “They fund our politicians.” In fact, Hopkins says, “Big Oil has been running our government for years. We need to wake up.”

Dirty Energy is a powerful wake-up call, showcasing the dangers of offshore drilling, the lackadaisical response of the industry to potential environmental and health crises and the inevitable result of government pandering to corporate donors. Imagine if the powers-that-be took it to heart and finally refused the tainted cash that fills their coffers.

Dirty Energy: The Deepwater Horizon Disaster, First-Hand Stories from the Louisiana Bayou, Directed by Bryan D. Hopkins, Distributed by Cinema Libre Studios, 94 minutes, $19.95.