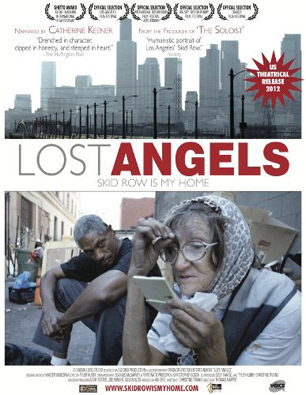

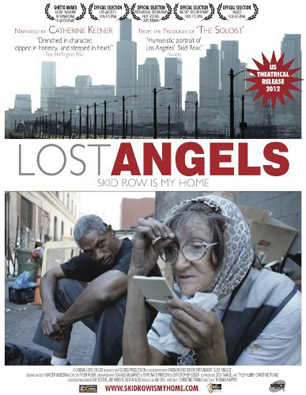

(Image: Cinema Libre)Thomas Q. Napper’s award-winning documentary, “Lost Angels”, writes Bader, “highlights the friendship, camaraderie and kindness that exist among the more than 11,000 undomiciled people – two-thirds of whom are struggling with psychiatric problems, drug addiction, or both” – living in LA’s Skid Row.

(Image: Cinema Libre)Thomas Q. Napper’s award-winning documentary, “Lost Angels”, writes Bader, “highlights the friendship, camaraderie and kindness that exist among the more than 11,000 undomiciled people – two-thirds of whom are struggling with psychiatric problems, drug addiction, or both” – living in LA’s Skid Row.

“Lost Angels: Skid Row is My Home,” a film by Thomas Q. Napper, narrated by Catherine Keener, 75 minutes. Released on DVD March 19, 2013, by Cinema Libre Studio.

Mollie Lowrey, founder and former executive director of Lamp Community, a program for homeless people in Los Angeles, describes that city’s Skid Row as “an open asylum for the mentally ill” in Thomas Q. Napper’s award-winning documentary, Lost Angels. But the film not only showcases people’s deficits, it also highlights the friendship, camaraderie and kindness that exist among the more than 11,000 undomiciled people -two-thirds of whom are struggling with psychiatric problems, drug addiction, or both -who call the area home.

It’s inspiring and awful, humbling and infuriating.

“Everyone on Skid Row has a story,” narrator Catherine Keener says early in the movie. And it is these stories – or at least the eight that Napper features in Lost Angels – that remind us that life is often precarious, and the collision between substance abuse, mental and physical illness, poverty and bad luck can cause a precipitous decline in just about anyone’s opportunities and choices. Add in the loss of thousands of units of low-cost housing, the closing of hospitals offering long-term psychiatric care and rampant gentrification, and it’s not surprising that there’s a crisis writ large.

“We don’t have closed asylums anymore,” Lowrey continues, “except for our jails and our prisons. LA County Twin Towers Jail is the largest mental institution in the United States. We no longer hospitalize the mentally ill; we criminalize them because of their behavior on the streets.”

This reality is obvious to most of the people in Lost Angels, many of whom languished for years before finding real help. Danny Harris is a case in point. Harris was born in Compton, California, and says that he began smoking weed in high school. Nonetheless, he excelled in track and field, was recruited to Iowa State University, and was given a full scholarship. At the end of his first year, 1984, the 18-year-old Harris secured a spot on the US Olympic Team and won a silver medal in the 400-meter hurdles. Three years later, he won another silver medal at the international championships in Rome. For a while he was on top of the world – lucrative endorsement deals flew fast and furious. But the high life began to shatter when, in 1996, Harris tested positive for cocaine and was promptly banished from the sport.

“I’d been freebasing cocaine since 1988,” he tells the filmmakers. “This was the beginning of a 20-year addiction.” Harris matter-of-factly describes his descent, including “lying down on the sidewalk,” but admits that his first foray onto Skid Row left him “pretty much horrified.” Still, he felt that he had no choice but to stay on the streets and keep using drugs. Then, in 2007, a chance encounter with a recovering addict employed by the Midnight Mission in downtown LA motivated him to begin the arduous process of getting clean.

A year hence, in a twist befitting a fairy tale, the newly sober Harris returned to Iowa State to complete the undergraduate degree he’d started 25 years earlier. He has since returned to LA, bachelor’s degree in hand, and presently works as assistant to the Midnight Mission’s president.

Harris’ recovery is not the only miracle noted in the film. Manuel “OG” Compito lived on the lam in Buffalo, New York, for eight years before being extradited back to Los Angeles. After serving a lengthy jail sentence, OG ended up on Skid Row, where the area’s filth enraged him. In short order he created OG’s N Service, a volunteer “brigade” that clears away garbage on San Julian and surrounding streets each and every day.

Others, including former gang member and ex-felon Steve “General Dogon” Richardson, also came to Skid Row after being imprisoned. The most political of the interviewees, Richardson now works for the Los Angeles Community Action Network, LACAN, to protect the human and civil rights of Skid Row’s denizens and protest ongoing police brutality.

It’s an enormous task. “For years, politicians turned a blind eye to Skid Row,” narrator Keener reports. That changed in 2006 when the city launched the Safer Communities Initiative, a $6 million a year effort that was touted as a comprehensive approach to helping people living on the streets. The theory, promulgated by Police Commissioner William Bratton, utilized the Broken Windows theory that previously had been implemented in New York City. The upshot was that minor infractions were targeted; in its first year alone, 9,000 people were arrested and 12,000 were given citations for jaywalking, sitting or sleeping on the sidewalk, or dozing in city parks.

The policy – still in place – continues to anger those on Skid Row. “If you have a beer in your hand it’s like you murdered someone,” one resident quips.

Meanwhile, the needs of most Skid Row residents remain unmet.

Lee Anne Leven, an elderly woman on the streets for 20-plus years, takes an enormous shopping cart filled with rubble everywhere she goes. “There is no clean, fresh water for the cats,” she grumbles. Her job, she continues, is to patrol the streets and leave food and water for the many strays she encounters.

“One day I saw some guy bothering her,” says Kevin “KK” Cohen, an articulate, soft-spoken man who appears as Leven’s constant companion in the film. Cohen says that he immediately intervened and, from that day forward, Lee Anne “adopted me as her fiancé.” Sure, he laughs, “she has storage units filled with trash that she pays for every month, but it’s what she likes. I would defend her with my life.”

His dream, to live on a horse farm with Lee Anne – he fantasizes about it as a place where she could collect as many containers and newspapers as she wanted and take in dozens of cats – was cut short in 2009 when he was murdered in a Skid Row lodging house. News of his passing – revealed at the end of the film – is shocking, and gives viewers a vivid glimpse into the dangers lurking on, or near, the neighborhood’s streets. At the same time, this is not a film steeped in random or intentional violence. In fact, Lost Angels celebrates men and women who live, work and create despite significant obstacles. Their spirit – in defying convention and challenging more mainstream notions of productivity and community – even as they battle psychological demons, is incredible.

Keener calls Skid Row a place of contradictions and presents it as a refuge filled with danger. She further reports that it is a place where healing and recovery are as possible as violence and death. Yes, schizophrenia, dementia, substance abuse, alcoholism and street fights are on display in Lost Angels. At the same time, generosity, love and true friendship are also visible. Indeed, unlikely as it sounds, there is great beauty to behold on the streets of Skid Row. It’s something to remember as we work to formulate respectful strategies to alleviate hunger, homelessness and want.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $31,000 in the next 48 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.