Here’s a look back at the work of this remarkable activist who is still engaged in the struggle for human emancipation.

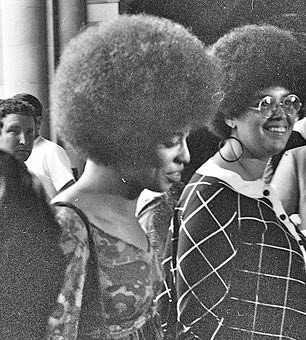

Her slender silhouette, her afro, her angelic face – they symbolise not just an era, but a struggle. The poet and playwright Jean Genet saw her as a woman with “tenaciousness so emotive it’s mystical.” Forty-one years after her release, Angela Davis is a revolutionary icon, a major figure in the struggle for emancipation, in feminism, a symbol of the black American struggle for equality.

Support Truthout’s mission. Angela Davis’s new book,”The Meaning of Freedom,” is yours with a minimum donation to Truthout of $25, or a monthly donation of $15.

The part of the world in which we grow up shapes us. In terms of racial segregation, Angela Davis was born in the first circle of hell. Birmingham, Alabama – the heart of the racist and secessionist south, where in 1955 Rosa Parks had the courage to carry out a fundamental act of rebellion. Davis’s earliest childhood memories were the blasting of bombs planted by the fascist Ku Klux Klan, so many that her neighbourhood became known as “Dynamite Hill”. She heard tales of a grandmother who remembered the days of slavery and “whites only” signs. Her parents were communists, actively campaigning against the Jim Crow laws establishing apartheid in the U.S. At fourteen, she left Alabama for New York thanks to a scholarship. In high school, she discovered the Communist Manifesto and made her first activist steps in a Marxist organization, Advance.

Angela Davis was a bright student. In 1962, she entered Brandeis University. In the first year, there were only three black students. She discovered Sartre, Camus, and was introduced to the philosophy of Herbert Marcuse, whose classes she took. She left in 1964, first for Frankfurt, then the crucible of heterodox Marxism. She studied Marx, Kant, and Hegel and followed the lectures of Theodor W. Adorno. In the US, a new wave of protests began against racist oppression and the Vietnam War. Upon her return in 1968, the young philosopher joined the Black Panthers and signed up to the Che Lumumba Club, a group affiliated to the Communist Party. A year later, in possession of a PhD supervised by Marcuse, she was appointed professor at the University of California Los Angeles to teach Marxist philosophy.

The profile of a twenty-five year old woman, her skin colour, beliefs, and convictions focused the hatred of an ultra-reactionary white American mind-set that then governor of California, Ronald Reagan, sought to harness. At the request of the latter, Angela Davis was fired from the university. This was the first act of a politico-judicial plot against the communist militant. Already active against the prison industry that crushed black youth, Davis took up the cause of three inmates at Soledad prison. With one of them, George Jackson, she had an epistolary love affair. The desperate attempt by Jackson’s younger brother to break him out of prison went awry. Jonathan Jackson, two other prisoners and a judge were killed in the shoot-out. Angela Davis was accused of supplying weapons to the attackers. Designated as public enemy number one, she was one of the ten most wanted people in the United States. For fear of being killed, she fled. A wanted poster describing her as “armed and dangerous” was plastered all over the country. Bearing a vague resemblance to Angela Davis – or just having an afro – was enough for hundreds of women to be arrested. The FBI deployed as part of its counter-intelligence program targeting communists and Black Panthers, disproportionate measures to hunt down what the white reactionary establishment called “the red panther ” or “the black terrorist”. But there was solidarity as “We would welcome Angela Davis” placards began to pop up on the doorsteps of friendly houses.

The fugitive was finally arrested on 13 October 1970, in New York. On television, President Nixon condemned her even before she appeared in court. “This arrest will serve as an example to all the terrorists,” he enthused. January 5, 1971, the State of California charged her with murder, kidnapping and conspiracy. Placed in isolation, she faced a threefold risk of getting the death penalty. An extraordinary international solidarity movement developed in India, Africa, the United States, Europe, with millions of voices demanding the release of Angela Davis. The Rolling Stones devoted a song to her: “Sweet Black Angel”.

Lennon and Yoko Ono wrote to Angela. In France, Sartre, Aragon, Prévert, Genet denounced the racism, and persistent McCarthyism of her arbitrary detention. At the initiative of Jeunesse communiste (Communist Youth), 100,000 people take to the streets of Paris on October 3rd 1971, in the company of Fania, Angela’s younger sister. L’Humanité was the voice of the solidarity movement.

She who always entered the courtroom with a raised fist was finally discharged on June 4, 1972 by an all white jury. While the verdict didn’t wipe out the racism of American society, it dealt it a serious blow. Released, Angela Davis did not give up the fight for emancipation, for another world, free from oppression and all forms of domination. In meeting her, Genet said he was “certain that the revolution would be impossible without the poetry of the individual revolts that would precede it.” Angela Davis still embodies this grace that gives meaning and nobility to political engagement.

Original French Article: Angela Davis: l’icône Sweet Black Angel à l’Humanité. Translated Saturday 13 April 2013, by David Lundy.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.