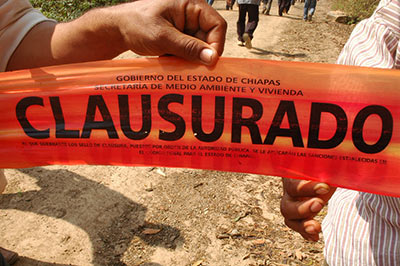

A fact finding mission looking into a case involving a Canadian exploration and mining company tapes off a mine site in Chiapas, Mexico. (Photo: Dawn Paley / Flickr)Canadian mining companies play a large role in the neoliberal exploitation of indigenous lands and workers in Mexico and South America. Not only do they often cause displacement of local residents as a result of NAFTA, many mines have unsafe work conditions, harsh labor practices and create a toxic environmental legacy.

A fact finding mission looking into a case involving a Canadian exploration and mining company tapes off a mine site in Chiapas, Mexico. (Photo: Dawn Paley / Flickr)Canadian mining companies play a large role in the neoliberal exploitation of indigenous lands and workers in Mexico and South America. Not only do they often cause displacement of local residents as a result of NAFTA, many mines have unsafe work conditions, harsh labor practices and create a toxic environmental legacy.

But, as David Bacon writes in his new book, against all odds, there are Mexican activists who are resisting inhumane and toxic mining practices:

When Fausto Limon, Veronica Hernandez, and the other Perote Valley residents began battling Smithfield Foods over environmental contamination and the political repression that followed, their problems weren’t unique. In many parts of Mexico, large corporations take advantage of NAFTA and economic reforms to develop a megaproject in a rural area. These projects often threaten or cause environmental disaster. Communities affected by the environmental and economic impacts are uprooted, and their residents begin to migrate. The projects themselves are defended against protests from poor farmers and townspeople by the federal government, whose economic development policy for decades has prioritized corporate investment.

This is particularly true for communities facing the vast expansion of huge industrial mining projects. One such project is the proposed Caballo Blanco gold mine near the Veracruz coast, which has faced stormy opposition. Even sharper conflicts have broken out over mines in Oaxaca. In one community, San Jose del Progreso, indigenous leaders have been assassinated and the town deeply divided since the mine began operation.

These conflicts shape the political terrain in which indigenous people are seeking alternatives to displacement and forced migration. The companies and their defenders promise jobs and economic development. But affected communities charge that far more people lose jobs and their livelihoods as a result of negative environmental and economic consequences. Meanwhile, the exodus of displaced migrants grows ever greater.

Oaxaca is also the state where the debate over how to end displacement and forced migration has become more intense than almost anywhere in Mexico. In part this is because poverty there, by many measures, is greater than in almost any other state except Chiapas. At the same time, the political movements that advocate for the right to not migrate, and for the human rights of migrants, are growing in political strength. They were part of the upsurge that defeated the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, and elected Gabino Cue governor in 2010. Now that administration is under pressure to make concrete progress in finding alternatives to displacement. One indigenous community, the Triquis, have precipitated a political crisis, as many demand a political solution that can make it possible for displaced people to return home.

In Veracruz, the Caballo Blanco mine was proposed during the six-year term of Governor Fidel Herrera, who left office in December 2010. A Canadian corporation, Goldcorp Resources, initiated exploration for two huge open pit excavations halfway between the state capital, Xalapa, and the Gulf Coast. The company, with headquarters in Vancouver, and its Mexican subsidiary, Minera Cardel, were virtually given a concession of more than seventy-seven square miles by the federal government.

The Herrera administration was notorious for allowing the Zeta drug cartel to operate freely. Even Mexico’s right-wing president Felipe Calderon at one point told reporters, “I believe Veracruz was left in the hands of the Zetas. I don’t know if it was involuntary, probably, I hope so.” Both Calderon, leader of the conservative National Action Party (PAN), and Miguel Angel Yunes, the party’s candidate for governor, were bitter over Angel Yunes’s defeat by Herrera in 2004. Yunes later told reporters that Herrera “handed over the police and police command to these criminal groups, and everyone in Veracruz knows it.” Even the Zeta’s rival Sinaloa cartel made a video in which they called Herrera “Zeta Numero Uno.”

Herrera’s laissez-faire attitude also applied to corporations like Goldcorp and Smithfield. Mexican environmentalist Tulio Moreno Alvarado compared the Caballo Blanco proposal to the Granjas Carroll pig farms. “The way the mine worked to overcome its opponents was very similar to that of the marginalized communities of Perote, although it’s important to understand that the damage the mine will leave behind is incomparably greater than what the pig farms will cause.” He estimated that Caballo Blanco’s impact would extend over seventy-five square miles.

Edgar Gonzalez Gaudiano published an analysis of the mine in the local newspaper, La Jornada Veracruz, in which he estimated that the mine would produce a hundred thousand ounces of gold a year, with a value of about $1,660 an ounce at May 2012 prices, or $166 million. Goldcorp would operate two huge open pits. The ore would be treated with cyanide, a strong poison, to leach out the metal. Cyanide bonds with the gold, essentially dissolving it. Later the gold is separated out, leaving a large amount of cyanide-laced wastewater. That runoff is held in huge open-air ponds.

Gold mining with cyanide is a very dangerous process, yet more than 90 percent of all gold extracted worldwide relies on its use. In Romania in January 2000, a dam on one such pond broke and about thirty-five million cubic feet of toxic wastewater and mud poured into the Danube River. The plume of cyanide traveled downstream, through Hungary and the former Yugoslavia, to the Black Sea, killing everything it touched. It was called the worst environmental catastrophe since the nuclear meltdown in Chernobyl.

At Caballo Blanco, each ton of ore would produce only half an ounce of gold, so mountains of cyanide-treated tailings would quickly rise around the pit and the wastewater ponds. According to the Diario de Xalapa, another local newspaper, leaching out the gold would require almost four hundred million cubic feet of water per year, depleting the aquifer on which rural farming communities depend. The wastewater itself would not only be unusable to residents but would poison plants and animals if it ever escaped the ponds.

An even greater danger might come from Mexico’s only nuclear power plant, Laguna Verde, less than ten miles away. The ore would be broken loose from the earth by virtually continuous explosions, using up to five tons of explosives a day. This section of Veracruz is geologically part of a volcanic region that includes some of Mexico’s most famous dormant volcanoes, including Orizaba, less than a hundred miles away, and the Cofre de Perote, which is even closer.

Even before people from the towns closest to the mine, Actopan and Alto Lucero, began to protest, they said they’d been threatened in order to get them to sell their land to Goldcorp. Beatriz Torrez Beristan, an activist with the Veracruz Assembly and Initiative in Defense of the Environment (LA VIDA, in its Spanish acronym), reported to La Jornada Veracruz that in a public hearing on the project, “they never said anything, but they came up to us at the end and told us they were afraid, that they’d been intimidated and felt forced to sell their land. There is definitely intimidation here, and they’re criminalizing social and environmental protest.”

As Granjas Carroll did in Perote, Goldcorp promised jobs and said the environment would be restored after the gold and metals had been extracted. “But we know that this can’t be,” Torres told reporter Fernando Carmona. “It’s impossible to restore an ecosystem that has been so damaged. You can cut down a tree and plant another, but you’ll never restore the complex ecological chain, with its many trees, birds and water.”

In February 2012, a Pact for a Veracruz Free of Toxic Mining was signed at a statewide assembly of environmental activists. “The 300 – 600 full-time jobs they promise for six years can’t compensate for the thousands of jobs that will be lost in pig raising and sustainable tourism in this region of Veracruz,” it declared. People signing the pact committed themselves to distributing accurate information about the exploitation of natural resources, alerting communities about potential threats, initiating legal actions, and organizing peaceful demonstrations. Signers pledged support to communities that resist and called for dialogue with authorities and companies based on respect for people and the environment. Other groups, including Red Mexicana de Afectados por la Mineria, or Mexican Network of Communities Affected by Mining, and Red Mexicana de Accion Frente al Libre Comercio, or Mexican Action Network on Free Trade, also organized opposition to Caballo Blanco.

Environmental damage from the mine is potentially so great that on February 28, 2012, during Veracruz’s environmental day, Herrera’s replacement, Governor Javier Duarte de Ocho, announced he was opposed to its operation. But one of the biggest problems faced by local municipalities, where people still have some power, and even states with leaders who respond to popular pressure, is that municipalities and states don’t make the basic economic decisions in Mexico. That power is in the hands of the federal government. On March 13, 2012, Goldcorp announced it had received its first environmental impact report from SEMARNAT, Mexico’s federal Secretariat of the Environment and Natural Resources, a major step toward operating the mine. Then, in May, SEMARNAT denied the company permission to start work. Nevertheless, LA VIDA warned that Goldcorp would undoubtedly appeal any denial, and that in any case, other Canadian-owned mines in Mexico simply operated without all the required permits.

Federal acquiescence to Goldcorp would not only be unsurprising – it is the corollary to its policy of virtually giving away Mexico’s mineral wealth. In 1992, Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari modified the country’s mining law. This was the same year he also changed Mexico’s land reform law to allow the sale of former communal (ejido) lands. Both changes were intended to allow foreign corporations to invest in huge projects in Mexico, and to protect those investments. A year later, just before NAFTA took effect, the ceiling on the amount of foreign investment that could be allowed in “strategic” industries (like mining) was eliminated.

Changes continued under Salinas de Gortari’s successors, with both the PRI’s Ernesto Zedillo and the PAN’s Vicente Fox increasing the number of mining concessions given to foreign corporations like Goldcorp and to huge Mexican mining cartels like Grupo Mexico. Taxes on mining operations were eliminated. Companies only had to make a symbolic payment for each hectare of land granted.

According to Carlos Fernandez-Vega, whose business column, Mexico SA (Mexico, Inc.), runs in the left-wing Mexico City daily La Jornada, the amount of land given in concessions reached 61 million acres at the end of Fox’s presidency in 2006 and then more than doubled, to 126 million acres, in just the first four years of his successor Felipe Calderon’s term. “In the two PAN administrations, about 26 percent of the national territory was given to mining consortiums for their sole benefit,” Fernandez-Vega charges. He based his column on a study by Mexican academics Francisco Lopez Barcenas and Mayra Montserrat Eslava Galicia of the Autonomous Metropolitan University in Xochimilco.

In 2010, Fernandez-Vega explains, Calderon granted almost 10 million acres in concessions, in exchange for which the Mexican government received $20 million. The foreign and domestic corporations given the concessions made $15 billion that year (a 50 percent increase from the previous year). Those earnings were 750 times what they paid for the concessions.

The Mexican Constitution, with its roots in the revolution of 1910–1920 and the nationalist government of Lazaro Cardenas of the late 1930s, puts forward goals for mining and other economic activity. They include, states Lopez Barcenas, “using natural resources for social benefit, creating an equitable distribution of public wealth, encouraging conservation, and achieving a balanced development for the country leading to improved conditions of life for the Mexican people.” The new mining law, however, says any potential resource must be utilized, which gives the exploitation of resources preference over all other considerations.

“Concession holders can demand that land occupied by a town be vacated, so that they can carry out their activities,” Lopez Barcenas writes. “If land is used for growing food, that has to end so that a mine can be developed there. Forests or wilderness are at the same risk. This legal requirement also applies to indigenous people. Their land used for rituals or sacred purposes, which contribute to maintaining their identity, can be leveled or destroyed. This provision violates ILO Convention 169, which protects indigenous rights.”

Language in the mining law now “prohibits states and municipalities from imposing fees on mining activity, and therefore deprives them of any income from those activities that might benefit them,” he says. It even prohibits them from charging fees for permits for the use of land or roads.

Copyright (2013) by David Bacon. Not to be reprinted without permission of the author or Beacon Press.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $17,000 by midnight tonight. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.