Part of the Series

Solutions

Whistleblowers are an integral part of the system for providing oversight of the federal government. Ensuring that these government missions are done in an effective and efficient manner is essential because of all the various internal agendas, problems of self-dealing and the constant revolving door by which private interests of small groups are injected into public policies. Whistleblowers play a significant role in protecting taxpayers from waste, fraud and abuse through disclosures to Congress, nonprofit organizations such as the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) and the media.

In order for whistleblowers to be an effective part of this oversight, they must have meaningful protection from agency reprisal for their actions. The Office of Special Counsel (OSC) is the official place they must look to for such protection, but this office is absolutely failing its stated role. Under Bush appointee Scott Bloch, the OSC began to act as the “Three Wise Monkeys” of Chinese legend. When a whistleblower requests help in fighting agency retaliation, the OCS hears no evil, sees no evil and does not speak about any evil. Unfortunately, this situation continues almost three years after Bloch was removed from the office.

OSC

The OSC has been charged by Congress to protect whistleblowers against retaliation. On their web site the OSC states, “The OSC's primary mission is to safeguard the merit system by protecting federal employees and applicants from prohibited personnel practices, especially reprisal for whistleblowing.” This mission is assigned to OSC by several federal statues, especially the Civil Service Reform Act (CSRA) and the Whistleblower Protection Act (WPA). The CSRA assigned this mission to the OSC. The WPA made some changes in CSRA, intending to extend those protections. In theory, this is how the act is supposed to work. I found out the hard way that the actual system is very different from its declared and legal mission.

My Experience With OSC

I experienced the lack of effectiveness of this office first hand. During my job as chief of the Field Support Contracting Division of the Army Field Support Command, I exposed internally and externally billions of dollars of excessive billing by KBR for their troop supply work in Iraq. Even with my 31 years of experience in military procurement, I could not fight the powers that be in the government. The Army moved me to another job, eventually pushed me into early retirement and paid KBR the billions of dollars in overruns that were charged to the government.

After the Army ignored my efforts to rein in KBR and following my early retirement in 2008, I began to publically criticize what I saw as favoritism toward KBR at the expense of the soldier and taxpayer. I testified before Congress on two occasions and initiated a Department of Defense (DOD) inspector general (IG) report on several actions taken by the Army at my command, the Army Sustainment Command, in 2004. All of these actions qualify as protected actions under the current WPA.

In 2010, I saw an opportunity to return to work with the Army and a chance to help to improve Army support contracting and save billions of dollars. I applied for a position and was not selected. I suspected that politics and my internal Army and public truth telling kept me from getting the job. After obtaining some documents under the Freedom of Information Act, I determined that it was obvious, on the face of those documents, that I had been held to a completely different evaluation standard than the selected candidate.

I filed a complaint with OSC and had my case settled well within their 240 day standard. They declined to investigate and closed my complaint. My complaint achieved nothing, except to help improve the OSC record of moving cases through without meaningful investigation, but very quickly. In the upside-down world in which the OSC is run, this actually made them look more efficient and improved their “performance metric.”

The reasons for turning down my case were fairly simple. The OSC told me I had not proved that a prohibited personnel practice had taken place and I had not proved that the action was done with intent to retaliate for my protected disclosures and actions. Both of the reasons given are not in compliance with the letter of the law and the intent of Congress when they passed the bill.

The OSC must report a violation if there are “reasonable grounds to believe” that the violation took place. By law, they decide this after they have conducted their investigation and reviewed any agency investigation or report. Throwing the reasonable grounds standard out the window, the OSC demanded that I prove that a violation took place prior to any investigation.

The WPA was designed to make it easier for a complainant to prove retaliation for whistleblowing in a corrective action before the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), a quasi-court system set up for federal workers to seek redress from retaliation. The special counsel need only prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the disclosure was a “contributing factor” in the personnel action. If they do so, then the agency must mount an affirmative defense of their actions.

Instead, the OSC placed an insurmountable burden of proof on me. They basically told me I could not prove the “intent” of the government actors, evidently because they had not supplied me with written confessions. The OSC twisted standard appears to be that reasonable conclusions regarding intent cannot be read from the actions of the participants, which is the common way we figure out someone's intent in any action. The WPA was expressly written to relieve the complainant from the burden of proving intent, but OSC has ignored this change in the law.

It is clear the OSC should have investigated my complaint, but chose not to. Every year this is the situation in which hundreds of legitimate whistleblowers find themselves in seeking a remedy for retaliation. This result becomes common knowledge and discourages future whistleblowers. I did some more digging into the OSC statistics and found I was not alone is my treatment by the OSC.

The WPA and the OSC

The WPA established the OSC as an agency independent from the MSPB. Its primary responsibilities, however, have remained essentially the same as set forth in its statutory predecessor, the CSRA. With the goal of protecting employees, former employees and applicants for employment from prohibited personnel practices, the OSC has the duty to receive allegations of prohibited personnel practices and to investigate such allegations.

The special counsel has several avenues available through which to pursue allegations, complaints and evidences of reprisals for whistleblowing activities, including:

-

requiring agency investigations and agency reports concerning actions the agency is planning to take to rectify those matters referred;

-

seeking an order for “corrective action” by the agency before the MSPB;

-

seeking “disciplinary action” against officers and employees who have committed prohibited personnel practices;

- intervening in any proceedings before the MSPB except in some rare cases.

Within 240 days of receipt of a complaint, the OSC is required make a determination as to whether there are reasonable grounds to believe that a prohibited personnel practice has occurred, exists, or is to be taken. This may be the result of the initial submission or of additional investigation by the OSC Investigation ND Prosecution Division. If a positive determination is made. there is a formal resolution process, involving an agency investigation and report. There is also the possibility of a criminal referral.

If in any investigation the special counsel determines that there are “reasonable grounds to believe” a prohibited personnel practice exists or has occurred, the special counsel must report findings and recommendations and may include recommendations for corrective action to the MSPB, the agency involved, the Office of Personnel Management and, optionally, to the president.

If the agency does not act to correct the prohibited personnel practice, the special counsel may petition the MSPB for corrective action. The MSPB, before rendering its decision, is required to provide an opportunity for oral or written comments by the special counsel, the agency involved and the Office of Personnel Management and for written comments by any individual who alleges to be the victim of the prohibited personnel practices.

The WPA made several changes in 1989, designed to ease the burden on whistleblowers to make a case of retaliation before the MSPB:

-

The special counsel need only prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the disclosure was a “contributing factor” in the personnel action, instead of a “significant factor.”

-

When the MSPB renders a final order or decision of corrective action, complainants have the right to judicial review in the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

- The standard by which an agency must prove its affirmative defense that it would have taken the personnel action even if the employee had not engaged in protected conduct was increased. This standard is “clear and convincing evidence” that it would have taken the same personnel action even in the absent of such disclosure.

Lack of Real Protection

So, what has gone wrong since the WPA strengthened the provisions of the CSRA? Unfortunately, many of us who have experienced retaliation for such acts have found out that the OSC is a relatively useless venue for seeking a remedy for retaliation.

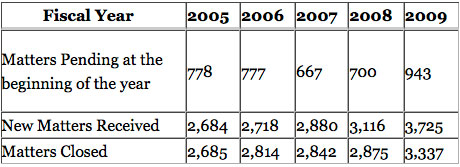

The statistics provided by the OSC Annual Report to Congress for Fiscal Year 2009 (the latest available report) tell a sad story. This report affirms the OSC mission described above. In the following table, the OSC presents data on their actions.

While the caseload of the OSC is increasing at a steady and significant rate, the number of cases closed is also increasing, as is the backlog, after a drop in 2007. Just looking at these figures, there is nothing particularly alarming. That comes the next chart.

Table 4 of this report is limited to complaints received that allege both violations of Merit System Protections and those violation complaints that allege retaliation for whistleblowing. Here, is the relevant part of that table:

Even with the steady increase in workload, the OSC has achieved an outstanding record on the metric where cases are closed in 240 days. As is painfully obvious, they achieve this metric by turning down most cases without even an investigation. In 2009, approximately 7 percent of complaints were referred for investigation by OSC. All other complaints were closed with no action taken. Certainly, it appears that the OSC is meeting its metrics the easy way – by simply not performing its mission.

Once a case is closed without investigation, the complainant may go before the MSPB, but with little chance of success. Without first an OSC investigation that should lead to an agency investigation of the matter, the complainant is left without access to documents, testimony and proof. In addition the MSPB has a natural bias to turn down any complaint that OSC declined to investigate. The OSC has become a place where whistleblower complaints go to die, even though this is the required route for redress by federal whistleblowers.

How Do We Change This?

The OSC has been a troubled agency for a long time. The special counsel under the Bush administration was Bloch. On April 27, 2010, Bloch pleaded guilty to criminal contempt of Congress for, according to the US attorney, “willfully and unlawfully withholding pertinent information from a House committee investigating his decision to have several government computers wiped.” The removed information included the documents rejecting the complaints of whistleblowers. During his tenure as the special counsel, Bloch was often criticized in the news for failure to investigate complaints, condoning discrimination against gays and purging the OSC of gays and other political opponents of administration policies. He was accused in the press of gross mismanagement and politicization of the office. He hired numerous graduates of third-rate conservative law schools, such as the Ave Maria School of Law which lists the OSC as employing its graduates. Many of these lawyers were hired on a non-competitive basis and then converted to career positions.

Under Bloch, the OSC routinely declined to investigate complaints of retaliation by whistleblowers. Bloch left in 2008, but the position of special counsel was not filled until the United States Senate confirmed Carolyn Lerner as the eighth special counsel on April 14, 2011. So, during the last two and one-half years the “career civil servants” have carried on the Bloch climate of ignoring whistleblower complaints.

How Do We Fix This Situation?

-

Lerner must take control of the agency and steer it to actually performing the statutory mission of the OSC. During her confirmation hearings, she promised to make things better for the whistleblower. She sounds like she has the right intent. However, she must institute new metrics of effectiveness to evaluate performance based on their original and stated mission, especially protecting whistleblowers. Her office has to set a new climate of not just getting cases processed through the system, but to win some cases and actually protect whistleblowers. She should also hold her workforce accountable for accomplishing the organization mission and sweep out any conservative agenda left over from the Bloch era.

-

Lerner must be provided the resources to actually investigate more than 7 percent of the complaints received. Since obtaining adequate funding from the House of Representatives will be a tough political fight, the administration should look at all ways to provide additional staffing for this organization, such as the reprogramming of current funds available for less important purposes.

-

The Senate must provide oversight of this office. OSC is considered as an inspector-general-type office and does not have its own internal IG. This makes the Senate as the only current option for this oversight. The Subcommittee on Oversight of Government Management, the Federal Workforce and the District of Columbia, of the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs is the appropriate venue. I am very familiar with revolving-door practices at federal agencies, so I believe that it is crucial that the Senate should ask the General Accounting Office to review whether OSC exhibits a bias against complaints that are not filed through one of the several law firms, which offer representation in filing such complaints. These are, of course, the firms where OSC lawyers will seek lucrative employment following their service at OSC. They may perceive an incentive to strengthen these firms as the only venue for getting a case investigated.

- The White House should establish a clear line of communication and public support for Lerner and she should have the administration publicly backing reforms at the OSC. The administration and the Congress should look at further strengthening the WPA to additionally encourage honest whistleblowing actions and protect the actors. Obama and other protectors of whistleblowers did a heroic effort to pass a comprehensive bill to fix the OSC and strengthen redress for whistleblower in the last session in Congress. They had the votes to pass the bill, but an anonymous hold on the bill in just the last few hours of the Congress killed it. The administration and the good government groups have reintroduced the bill and one of the main solutions would be to get it passed this time and expose all members that try to stop it. Perhaps Obama should look at a 2007 poll that shows that protection for whistleblowers is not only the right thing to do, but is politically popular, especially in an election year.

As always, solutions in the best interest of the country are obtainable. The question is the political will to implement them. We all must continue to advocate for this kind of change so that our government can work better and the undue influences on it are exposed. In these tight fiscal times, whistleblowers' information and protecting their rights should be growing, not just for them, but for the rest of us as well.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.