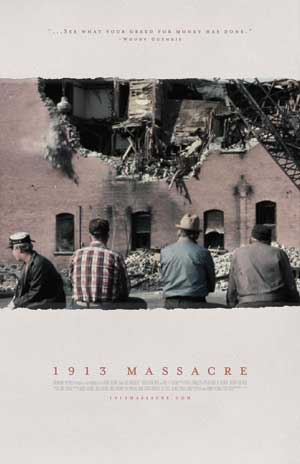

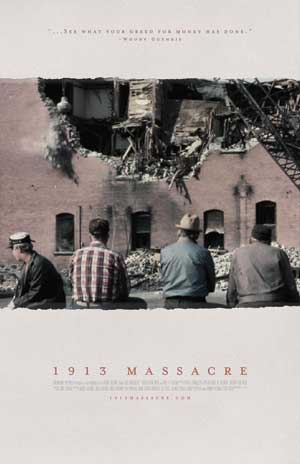

(Image: Dreamland Pictures LLC)Producers of the new documentary, “1913 Massacre,” Louis Galdieri and Ken Ross, talk about their movie and the tragic deaths of 74 at a union Christmas Eve party sponsored by the Western Federation of Miners.

(Image: Dreamland Pictures LLC)Producers of the new documentary, “1913 Massacre,” Louis Galdieri and Ken Ross, talk about their movie and the tragic deaths of 74 at a union Christmas Eve party sponsored by the Western Federation of Miners.

It’s been a century since the tragic Christmas Eve stampede at Italian Hall in Calumet, Michigan, but the pain of that history still runs as deep today as the town’s copper mines of old. As the story goes, a Christmas party was sponsored by the Western Federation of Miners. They had organized a strike, and worker families gathered for the festivities. Situated in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Calumet was a battleground in the blood-soaked pages of labor history in the United States. Someone that night yelled “Fire!” causing a panic. The doors of Italian Hall did not open, and in the rush in its staircase, 74 in total, 59 of them children, suffocated to death. There was no fire.

On Christmas Day, Calumet Theatre served as a temporary morgue before a funeral procession made its way through the somber town. A new documentary, 1913 Massacre, inspired by a Woody Guthrie song explores the history of those days in a heartfelt manner. The film begins at Calumet Theatre with folk singer Arlo Guthrie’s performance there when he offered a rendition of his dad’s tune that told the tale of the tragedy. Then Louis Galdieri and Ken Ross, producers and directors of the documentary, spoke with survivors, relatives and residents of Calumet to create a vivid portrait of a people coming to terms with their past.

“I’m Italian-American, and I’ve always been interested in stories about Italians coming to America,” Galdieri says. The historic hall suggested there was one to be found in Calumet. But first, the filmmaker was inspired by Woody Guthrie’s powerful song. “I must have been about 17 or 18 years old,” he says, when he first heard it. “It made an impression – a deep one. The song rolled around in my head for a long time. It wouldn’t leave me alone. And the first few lines played like a loop.”

Guthrie’s ballad eviscerating the copper bosses opened with the words, Take a trip with me in 1913 / To Calumet, Michigan in the Copper Country / I’ll take you to a place called Italian Hall / Where the miners are having their big Christmas ball.

Galdieri took a trip out there himself, with camera in hand, to see if the history still reverberated through the town. “Louis came back from that trip and asked if I’d like to travel with him to this remote place, a place that seemed frozen in time – that was the phrase he used,” says Ross. Galdieri had done a sidewalk interview with a resident asking if she knew anything about Italian Hall. “She just looked into the camera and started crying,” Ross says. “Something was still there 100 years later.”

The documentary captures the tragic episode in the epic struggle between labor and capital in a chilling, haunting fashion. Historical images of an open mass grave, dead children and their tiny coffins couldn’t underscore the emotional weight of what happened that day any more effectively. Much to the filmmakers’ surprise, they were able to tell the story through survivors of the stampede itself. “When we first started the film, we were told repeatedly that they were all dead,” Galdieri says.

Mixing it up with regulars at a bar in town led them to Mary Butina, Julia Pichiottino, Tony Sayotovich and others. “We met Irene Taylor, who stood up on her tiptoes to watch the funeral procession pass by,” he adds. “She was only 3 years old at the time. These were people whose memories stretched back almost an entire century!” The testimonials of survivors are definitive in giving the film a living pulse to the past. “My grandma didn’t have a Christmas tree for years,” says a relative, about the painful memories the holiday aroused.

Around the time of the tragedy, the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company was the king of copper. That translated into jobs for European immigrants, but working conditions were miserable. “They used to call Calumet ‘the smelting pot,’ says Galdieri. “I went there looking for an Italian story, and Ken and I found a story that was about Finns, Slavs, Croats, Cornishmen, Poles, Czechs, Frenchmen and so on.” The fight of the immigrant working class to improve their lot divided the town. The atmosphere was antagonistic. Labor legend Mother Jones visited to rally miners and hell raise. “Calumet was a battlefield,” says an interviewee from the film.

Disputes about the history of the Italian Hall Massacre remain. Residents are tightlipped about some of the more sensitive details of what happened. The identity of the person who yelled “Fire!” has never been known, although there are ideas surrounding that question that people in the film would not discuss in front of the camera. There’s also a lingering debate over whether or not the doors of the hall opened inward or out. The inward theory lends thought to the tragedy being a result of structural entrapment. But if the doors of the hall opened outward, anti-union thugs held them shut. As it stands today, only a memorial arch remains from Italian Hall, as it was demolished in 1984, without good reason save for fear of its ghosts.

Calumet Theatre still remains, and it was there that the filmmakers hosted their most important screenings last year, the centennial of Woody Guthrie’s birth. “Sitting there with the audience, we could hear people sobbing, sighing, groaning. They laughed too, at all the right places” Ross recalls. “At the end of the first screening, a man in the back of the crowd stood up and shouted, ‘You made this old man cry!’ ”

The mines shut down in 1968. Calumet took an economic hit like other de-industrialized areas of the United States. “Maybe that’s all we have left is history,” says a townswoman in the film. There was talk of opening them back up, but their environmental pollution is another legacy that lingers. Near the end of 1913 Massacre, Arlo Guthrie recounts being recognized in Calumet, as a man brought back a red brick from Italian Hall to give to him. After the demolition, residents saved them, holding onto a history that, after a century, still very much has a hold on them.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $31,000 in the next 48 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.