Someday, one way or another, Greece will exit from its current state of indentured servitude. But what will it do for a living? I often hear assertions that the answer is “nothing.”

“What can the Greeks export?” the critics ask.

In general, my response to such claims is that those commentators suffer from the fallacy of misplaced concreteness: An economy, even that of a small nation, is a very complex thing, with more possibilities than a casual top-down overview can reveal.

Still, it’s nice to see Kemal Dervis — who is the vice president for global economics at the Brookings Institution and someone who actually knows something about the Aegean economy — weighing in with some specific ideas. “As a member of the E.U. and as a high-income country, despite current difficulties, Greece’s growth cannot be based on being a manufacturing hub for simple products produced with low wages,” Mr. Dervis explained in The Financial Times on July 7.

Mr. Dervis continued: “A high-quality tourism sector will remain central in Greece’s future, strengthened and complemented by more cultural activities, retirement communities from northern Europe and high-quality medical services at advantageous costs … It should find niches in the high-technology sector and participate in its worldwide structure. Finally, with considerable potential for wind and solar energy, green technologies can, in the longer run, become a major source of growth.”

That sounds plausible. Basically, Mr. Dervis is saying location, location, location — and surely that’s right. A spectacular archipelago in a wonderful climate that’s part of Europe should offer many opportunities once Greece is no longer being crucified on a cross of euros.

Help Truthout build a future for commercial-free journalism: become a Member today by clicking here.

All Greek to Him

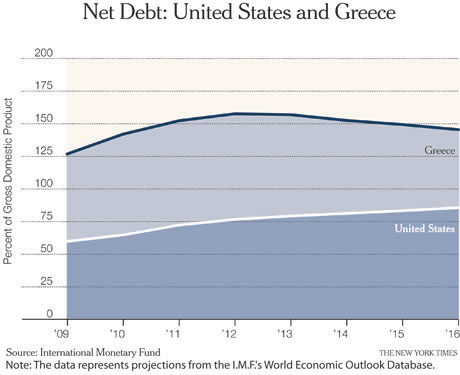

I’ve been complaining for a while about the Hellenization of economic discourse — the way everyone is being treated as being just like Greece, when in fact Greece (with a long history of fiscal irresponsibility, very high public debt, and without its own currency) doesn’t bear much resemblance even to the other peripheral European nations, let alone the United States.

Yet Mitch McConnell, the senator from Kentucky, declared recently at a press briefing that, “We look a lot like Greece already.”

Yep, aside from the fact that everything is different. The graphic on this page shows American and Greek debt levels, based on data compiled by the International Monetary Fund (if you ask me, the I.M.F. projections for Greece are too optimistic.)

Plus there’s the having-your-own-currency thing, and the fact that the interest rate on 10-year bonds in the United States is 3.11 percent, while on Greek bonds it is 16.82 percent.

Otherwise we’re exactly the same.

Also, didn’t Republicans used to accuse people talking down America of being unpatriotic?

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Paul Krugman joined The New York Times in 1999 as a columnist on the Op-Ed page and continues as a professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 2008.

Mr Krugman is the author or editor of 20 books and more than 200 papers in professional journals and edited volumes, including “The Return of Depression Economics” (2008) and “The Conscience of a Liberal” (2007). Copyright 2011 The New York Times.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.