(Image: Pulse Films)One of the most provocative movies to come out this year made its public debut in Washington, DC in April—not at the ritzy E-Street movie theater, but at “Rising Voices for a New Economy,” a joint summit of National People’s Action, a network of urban and rural grassroots organizations, and the National Domestic Workers Alliance, a leading voice for low-wage workers in the United States. Nothing could be more fitting, for a movie about the hazards of immigration to the United States, than to screen it before an audience of immigrant domestic workers and grassroots community leaders who themselves have suffered the risks and dangers the movie so vividly conveys.

(Image: Pulse Films)One of the most provocative movies to come out this year made its public debut in Washington, DC in April—not at the ritzy E-Street movie theater, but at “Rising Voices for a New Economy,” a joint summit of National People’s Action, a network of urban and rural grassroots organizations, and the National Domestic Workers Alliance, a leading voice for low-wage workers in the United States. Nothing could be more fitting, for a movie about the hazards of immigration to the United States, than to screen it before an audience of immigrant domestic workers and grassroots community leaders who themselves have suffered the risks and dangers the movie so vividly conveys.

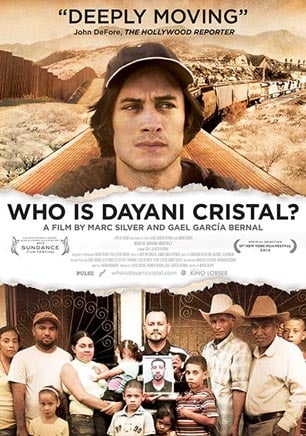

Who is Dayani Cristal?, a film by Gael García Bernal and Marc Silver, portrays death in the desert. In the current political debate over immigration reform, discussion has seesawed between legalization of 11 million undocumented immigrants in the United States on the one hand and increasing border security on the other. Lost in that conversation is the shocking number of migrants who have died crossing the border—in 2013 alone, for example, the U.S. Border Patrol found the remains of 445 likely migrants in the desert.

With massive spending on border control making it more difficult for migrants to cross in populated areas, people mainly from Central America and Mexico increasingly pass through south Texas or the Arizona desert, where many die of dehydration and exposure. As director Marc Silver pointed out in the discussion following the film screening, with militarization of the United States-Mexico border set to increase over the next several years, the number of deaths will only rise.

Piecing Together a Mystery

The movie proceeds like a detective story in three strands.

In one narrative, forensic specialists in Arizona painstakingly look for clues on the body of a dead migrant who has been found in the desert, 20 minutes south of Tucson. They repeat a ritual that they enact hundreds of times each year—they record the state of decomposition, check fingerprints against federal databases, reproduce body tattoos, take dental records, and analyze belongings in search of something that might help them identify the body. On the body featured in this film, the most notable clue they find are the words “Dayani Cristal” tattooed across the man’s chest.

In a second strand, a family in Honduras yearns to find out what happened to a father who set off to cross the border into the United States in order to afford health care for his ailing son. The man’s relatives talk about his dreams, the economic pressures he faced, and the choice he made to leave his family in order to help them.

The third quest takes place as famed Mexican actor Gael García Bernal sets out from Honduras to trace the steps that the man with the words “Dayani Cristal” on his chest might have taken on his way to the United States. García Bernal rides a bus from a small town in Honduras, makes his way across Guatemala, and boards a raft to cross the river into his native country, Mexico. Along the way, he plays soccer, shoots pool, shares food, and continually chats with migrants he meets, trading stories of where they are going and why, the dangers and the risks, the best and the worst tactics for getting there. In one particularly striking scene, García Bernal climbs aboard a train—not to enter one of its cars, but to sit atop them with the dozens of other men on a dangerous rail trip through Mexico.

Each strand of the movie humanizes migrants in a different way. The first brings human identity back to a body that had begun to decompose in the desert. The second shows the family and community context that migrants leave behind when they depart for the United States. The third helps us experience the journey north, in both its danger and its mundanity. At the film’s end we learn the surprising answer to the movie’s title, and the role it plays in connecting the three strands of the story together.

The Impact Goes On

Once the movie had ended—after García Bernal had at last crossed the border into the United States and walked across the Arizona desert, retracing the days and hours that led to the man’s death, and after the relatives in Honduras had received their loved one’s body back and buried it —the emotional impact of the film had only begun.

At the “Rising Voices for a New Economy” gathering, most of the audience was made up of immigrant workers. And for many, seeing the film had visibly touched off painful memories. Recognizing the intense feelings present in the room, the discussion’s moderator asked audience members to talk for a moment with the person beside them about their experience of watching the film. And she announced that trained counselors were waiting outside the auditorium to help people process their grief.

Woman after woman from the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) went to the microphone to tearfully and courageously tell their stories—of leaving family members behind in home countries, of having relatives nearly die while journeying to the United States, of facing intractable economic situations that forced relocation, of fleeing civil war. Yet most powerful was the fact that these were not individuals suffering in silence, but women organized into a strong association, fighting together for justice on immigration and fair labor practices. Through NDWA, immigrant domestic workers have been at the forefront of creating a broad women’s movement in support of humane immigration reform, and have led successful campaigns to pass Domestic Worker Bills of Rights in New York, California, and Hawaii.

Nor is this the only time the movie will have such a direct and palpable emotional and political impact. The directors have arranged to make the film available at any cinema where organizers can collect 50 people to watch it, so that migrant communities can discuss it together. They have also made a 20-minute version to show on Capitol Hill, to reach politicians with little time but much need for education. They have made sure the film will screen in Latin America. And they have made room on their website for migrants to tell their own stories, for people to take action in support of migrants, and for families to search for missing loved ones.

It is those moves toward accessibility, visibility, and action that give the film the potential to make an impact on the immigration debate—where the corpses have been invisible, and the migrants have been treated as less than human, in life as in death.