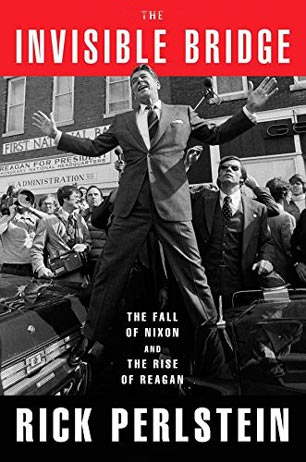

The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan. Simon & Schuster. 880pp, $37.50

If Rick Perlstein had done no more than put US history of the 1970s back near the top of the “controversy” pile of the daily news overflow, he would have accomplished something significant. For one thing, his Invisible Bridge has elbowed aside some of the bilge on the bestseller list like Bill O’Reilly’s seemingly endless series on murders-in-history. For another, it reassures us of the justice in our disgust at recent-history volumes turned out by faux public intellectuals like Thomas Friedman. And even if Perlstein is in too much of a hurry and too weighted down with details to turn out a classic like Eric Foner’s The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, The Invisible Bridge and its readership – as well as its critics – tell us a lot, and not all of it about recent history.

Perlstein is now working on part four of who knows how many volumes treating American liberalism’s crises and slow decline, which is to say, American conservatism’s rise and triumph. It’s a thankless job, but one to which Perlstein is equal. With a deft touch and real humor, he has made the demise of democracy seem almost fun – at least to learn about. Even his most agitated reviewers, not least Sam Tanenhaus in The Atlantic, are enjoying the chance to express some stale bile. His most expectable critic – The New Yorker’s hawkish George Packer who reveled in the latest Morning in America (aka the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq) – seems to be saying that the 1970s never left us at all.

The text is so intense that I imagine it will attract a very particular generational readership, one the author may not have intended. He is offering real wisdom to young and old, but the generational survivors of the activist 1960s and 1970s will have their own insight to bring to this volume. Nothing is quite so strong here as the author’s expert treatment of the calculated political response to what its perpetrators realized would soon be a US military defeat in Vietnam: This, more than anything else, is what set the national demons loose, just when we optimists thought that the defeat would summon a generation to transform American society in quite another way.

Famed Holocaust historian George Mosse devoted much of his later work to the political and cultural consequences of Germany’s defeat in World War I, the most important of which was of course the rise of the right wing. The left had no emotionally effective response except to deny they had ever supported the disaster of the war (which was not quite true: Mainstream socialists had loyally supported war budgets). The right, by contrast, appealed with great success to the wounded egos of the wounded, and the relatives and communities of the dead. The nation, infamously, had been stabbed in the back and robbed of victory, the right wing argued, by Marxists, liberals and especially by Jews.

Perlstein describes a similar process in the 1970s United States, one that required an aggressive manipulation of public opinion. The heroization of the Vietnam POWs reflected the sacralization of the German war dead and war wounded, granting them eternal honor for their sacrifice, while opponents of the war earned eternal contempt. Never mind that the POWs themselves, like so many other Vietnam veterans, along with their wives and families, expressed great bitterness at the US government and the political war makers for lying about the war through their collective teeth.

The up-raveling of the Ronald Reagan story brings Perlstein to another kind of mythos, namely his accepted but imaginary biography. Even the stories of how the boy got the nickname “Dutch” were faked, as was his role in the Hollywood union struggles of the 1940s, his actions during the McCarthy-era film blacklist and the reasons he chose just the right moment to change political parties. Readers of other Reagan biographies are not likely to learn many fresh facts here, but they will be reminded of crucial details, and of Reagan’s cunning in his climb to the top.

Still, it all comes back to Vietnam and the utter failure of any president to come to terms with the consequences of one of the great disasters of the 20th century. The Church Committee, in examining the misdeeds of US intelligence agencies, has been much written about, for instance, but Perlstein has added something new in his keen analysis of the press cover-up (with a few honorable exceptions). Helpfully, he references Jonas Savimbi, a great favorite of the CIA and also murderer of somewhere between a quarter and a half million Africans. And he names the sponsors of the Chilean coup, including the famed liberal New York Times commentator Anthony Lewis, whose cynicism, famous then, is here made famous again.

We move through the decade, and among the memorable portraits is one of Jesse Helms, a brilliant self-publicist and acute strategist who was fortunate enough to corral some of the richest right-wing funders in the United States (or the world). Before his shift from Democrat to Republican in 1970, he had enjoyed the support of the party of FDR and JFK, its leaders ever eager to bend in the direction of political convenience. This observation is a hinge of Perlstein’s book, although it appears in various chapters so subtly that the reader might miss its significance.

Some reviewers have insisted that Democrats drifted too far leftward on affirmative action and that Perlstein makes the case for them. Not so. Who can forget that affirmative action was bitterly opposed by labor leader George Meany and the fast-rising head of the teachers union in New York, Albert Shanker? To the contrary: Perlstein’s analysis of Jimmy Carter’s rise and fall shows how he moved the institution of the presidency to the right, even if Jimmy has had a great and sometimes admirable late career playing the ex-president as regretful moralist. Carter had never opposed the Vietnam War, certainly not in public, and Reagan worked that nerve in public to good effect. Rosalind Carter once remarked that Jimmy lost re-election thanks to three letters of the alphabet, “O-I-L,” in other words, the Iranian crisis. The United States, in the hands of centrist Democrats, was as disabled in dealing with foreign policy as German socialists were 50 years earlier, persistently managing to defeat themselves (and the rest of us).

And yet, perhaps Perlstein’s critics have unintentionally touched on one crucial point that’s missing from The Invisible Bridge. So much of the 1970s, in the memory of the Vietnam generation, actually promised a movement in the other direction. If the proto-revolutionary aspirations on campus and in the ghetto had failed, so much else happened that seemed to redeem the promise, and keeps on happening.

Consider, for instance, that the cultural expressions of the resistance had begun to take form only as the 1960s ended. Brilliant multicultural posters, wall murals, underground “comix” (I published one of them), all proliferated even as the underground press went into a steady fade. Women’s art, against the background of the women’s liberation movement, advanced dramatically and arguably returned the human being to the center of the public debate.

Or consider the rise of the electoral and educational coalitions in many scattered communities that took hold, rallying voters, merging what remained of the left with a liberalism broadened by the debate. In 1973, Madison, Wisconsin, elected a young antiwar activist mayor who surrounded himself with activists who fought rapacious landlords and transformed the local labor movement. In the wake of the failed McGovern candidacy, the hawkish wing of the Democrats set themselves to wipe out the left, but enthusiastic youngsters and many oldsters joined forces to resist.

On the subject of blue collar America, Perlstein suggests the battle was being lost to the right. By 1970-71, when strike waves reached a level not seen since 1945-46, things seemed very fluid. One of my best pals from those days, an Air Force veteran who recalled the moment during the Cuban crisis when he’d vowed to take a few Russians down with him as the world went up in flames, went on to become an SDS chapter leader, then a union activist. I ran into him a year ago, exiled to central Europe, retired after an assortment of fairly menial jobs, in poor health but full of distinctly radical memories. He spends a lot of time on the web, checking out the damage to the planet and its inhabitants. But his eyes light up when we talk about the old days that lasted, in one way or another, until the dawn of Reagan. He had been, in those days, not geographically far from where I found myself, in deeply blue collar Rhode Island, where threatened plant closings along with the heightened struggles of teachers and nurses sparked not only a militancy, but also a deep sense of community and continuity. “They” could not keep defeating us, smashing up the social contract that had been so long in the making.

Of course, “they” did. But paralleling the Reagan counter-revolution would be the Chicago victory of Harold Washington and the emergence of a multi-racial progressive movement. The nuclear freeze movement was waiting to happen, as was the rallying of black politics that led to the Jesse Jackson campaign of 1988. Not that any of these groups won, either.

None of this disproves Perlstein’s thesis, of course, or even argues strongly against a seeming inevitability of the rightward drift. “They” had the money, more of it politically than anyone could imagine, and they had in hand the millions of Americans who felt wounded by the Vietnam humiliation and eager to be redeemed by draping the nation in flags. Those of us who watched the public relations redemption of the newly “noble” war felt mostly paralyzed by the process, as if we were watching something awful happening in slow motion.

So Perlstein is right and has written an important book more radical in its implications than most readers will grasp. That’s good: Let them read, and learn.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.