It is always a bit of a surprise when Americans learn that a poet or any writer taught in basic literature classes was terribly radical, perhaps suspect in the day for dangerous ideas or behavior and, in some ways or at least among some audiences, barely acceptable even now. Walt Whitman’s homosexuality, pretty much undisclosed to the public for generations, has become since the 1960s the subversive side of Walt’s reputation, and for good reasons. His same-sex imagery is pretty clear as well as brilliantly poetic in his writings and assorted wonderful anecdotes (like his possible interlude with a visiting Oscar Wilde) seem to confirm suspicions. Never mind that the term “homosexual” was not used in his lifetime; gender relations were so differently configured that he could kiss, cuddle and such without the conclusions that later generations drew for themselves and others.

That Walt was still more radical has been known to insiders since the intimate young friend in Walt’s last years, later ardent Philadelphia socialist Horace Traubel, convened an annual Walt Whitman Fellowship event with notables that included socialist champion Eugene V. Debs. Traubel’s Conservator magazine, a literary weekly of politics and culture, brimmed full with the same message, including Traubel’s own Whitmanesque poetry. In the time between the last publication of Leaves of Grass during Walt’s days, and his sweeping recognition as a modern poet, Traubel and his circle had done much to keep the Whitman legend alive.

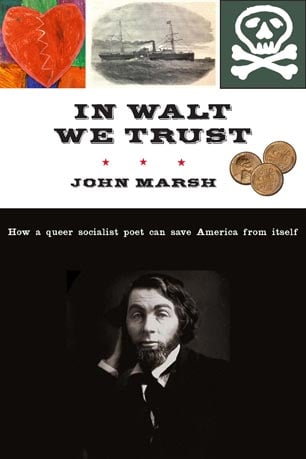

In Walt We Trust is a sprightly, extended essay or first-person peroration by a young lit prof who felt a ton of frustration and heartache, or at least headache (self-medicating with alcohol, he tells us), and in despair, threw himself at Whitmania. That is, the poetry, the life, the setting and the aura. The project was obviously successful and not only because of the resulting book. He feels, he insists, better about life, death and even sex – the trifecta that pretty much wraps up human earthly possibilities. But he had to take a gloomy field trip to Camden, New Jersey, to get his mind in place.

Camden, of course, is a boat ride from Philly, a ride that teenager Traubel took regularly to meet the aged poet, and in the 19th century, a lovely place. Now it is a mess, one more part of destroyed-urban Jersey, industry-abandoned, drug-infested, with its poor and nonwhite populations struggling just to get by. Especially depressing to Marsh is the cemetery monument to Walt, mostly because the whole idea of Whitman belonging in one spot rather than the world (like the scattered ashes of WWI martyr Joe Hill, for instance) is offensive, and for that matter, the monument is in a ruined site, unlikely to be visited by the masses who still read and love Whitman.

Marsh makes a happier trip to Brooklyn, where Walt spent decades, and rides a modern counterpart to the famed ferry that transported the poet to Manhattan. He goes onward to Washington, DC, visiting the very federal Patent Office building where Whitman tended the wounds of Civil War soldiers, including some Confederates, eased their suffering and often enough their dying. Scores of Whitman scholars have visited the same sites, preparing scholarly papers and volumes, while, others – and not only scholars – have engaged in sentimental journeys and still engage in them. It is hard to think of a radical American poet since Whitman to inspire quite so much outpouring of emotion, although in recent decades, Philip Levine or Toni Morrison devotees might perhaps compare in passionate fan outpouring.

The ultimate source of Marsh’s own passion for Walt can be found in what Horace Traubel and friends, within a memorial volume published a few years after the poet’s death, called “Cosmic Consciousness.” Whitman notoriously treated the body as holy rather than unclean, as the standard Christian version would have it, and argued in his poetry and prose that since nothing in the universe is ever lost, individual death is no big deal. This sounds straightforward today, in postmodern mentality, as credible in the wacky sense that anything, any philosophy no matter how apparently strange, is about as credible as any other. Why should the evangelical excesses of assorted politicians in Congress or the state houses be considered less weird? Whitman’s beliefs were shocking for most mid-19th century Americans, insufficiently comforting in the decade after the Civil War, when so many sought heavenly rewards for martyred husbands, fathers and sons. Perhaps more shocking yet: Sex is or should be not only divine, but also fun! As in,

Come closer to me,

Push close my lovers and take the best I possess,

Yield closer and closer and give me the best you possess

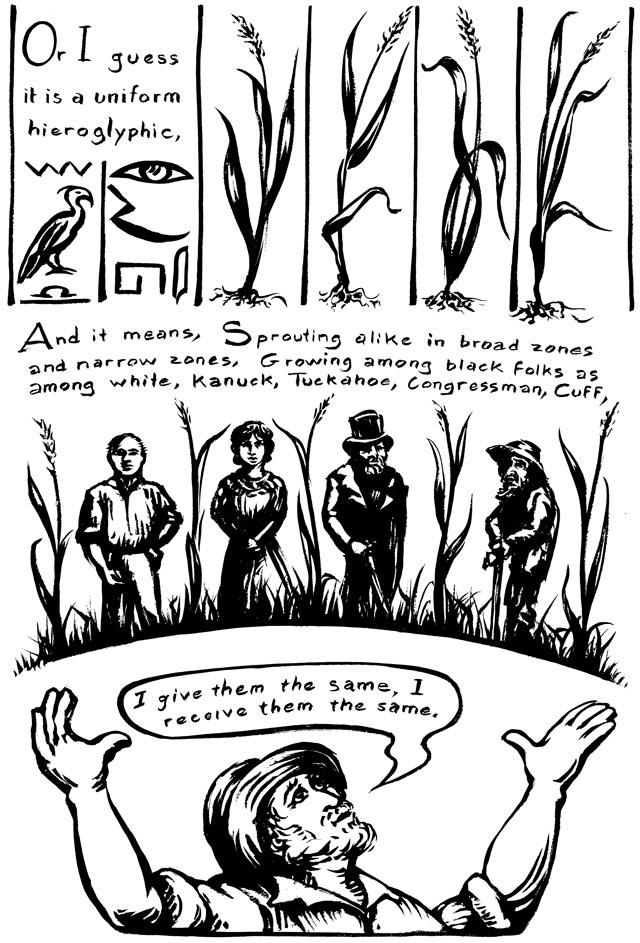

And this in a poem more about egalitarian economics, a fair chance for everyone, than about eros! The cheerful meeting of contraries was never far from his mind.

We can pause to wonder at Whitman’s own sources of inspiration. The mind-traveling Swedish royal scientist of the 18th century, Emanuel Swedenborg, had inspired poet William Blake, several of America’s founding fathers, and Emerson (himself a Whitman admirer). John Chapman aka Johnny Appleseed, the tree-planting pacifist of the frontier, himself a mystic of Whitmanian qualities, dreamed of founding a Swedenborgian college in Ohio.

American Spiritualism hit its peak during the 1850s, and Whitman, no avowed disciple, may have been its truest poet. Walt We Trust is dedicated to showing us what grandeur Walt intended for an expanded human spirit. If we look a little further to the political left, we find Victoria Woodhull, the notoriously avowed free lover and publisher, printing the first US edition of the Communist Manifesto in her newspaper. Woodhull was also president of the American Spiritualist Association.

Whitman was never quite so political. But in the optimism of his youth and early middle age, the expansion of the soul that he had in mind seemed to him within reach for all Americans, at least from the stance of his own social class, the artisans in an expanding economy. Leaves of Grass, in ever-new editions, would preach the egalitarian truth for all to hear, as he became (in his projections) the people’s poet.

And then, in the era after the war, came the downfall of the era’s sweeping idealism – woman’s rights to abolitionism – and with that downfall, the exposure of what he called “the great fraud of modern civilization.” The consolidation of the new order brought the “shameless stuffing [oneself] while others starve.” Taking a hard and pained look around, he saw “the depravity of the business classes of our country” growing ever greater.

Whitman could not go much further than this, even while blessing the commonest working person’s labor and life, the impoverished mother and child, as equal to any in dignity and rights. In the years shortly before his death, as Horace Traubel was copying down six volumes of conversations, Whitman admitted to his young admirer, “I’m a good deal more socialist than I thought I was. Maybe not technically, politically so, but intrinsically, in my meanings.” Later on, after a prominent English socialist intellectual had visited the two men, Traubel pressed the point, asking what about political platforms and such. “Of that I am not sure,” Whitman admitted, “I rather rebel. I am with them in the result – that’s about all I can say.”

Very likely Whitman was indulging the young devotee. He may also have been responding to the intellectual enthusiasm around the publication of two great utopian novels, William Morris’ News from Nowhere, a literary masterpiece, and Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, no literary masterpiece but a huge best seller. Socialism, or at least the idea of socialism, seemed to be coming into its own even as Whitman faded away.

Others, notably the gay British essayist Edward Carpenter, were busy preaching the glory of the body by the 1890s; Oscar Wilde was famously ridiculing sexual (and every other kind of) hypocrisy; and Henrik Ibsen was nailing the double-standard. These and others were making way for what seemed certain to be a better, because freer, century ahead. Whitman had laid down the shamefulness of sexual shame decades earlier,

Without shame the man I like knows and avows the deliciousness of his sex

Without shame the woman I like knows and avows hers

Behind and beyond the Sex Talk was the craving for a society so different from our own that it would become a republic of affections, something like the opposite of the dog-eat-dog morals that govern neoliberalism quite as much as neoconservatism. Of course it would mean the end of homophobia, along with so many other phobias. But the negatives that seem so powerful today and need so desperately to be overcome would, in the eyes of Whitman and his scholarly personal disciple, John Marsh, surely be overcome. That’s the dream, unrealized.

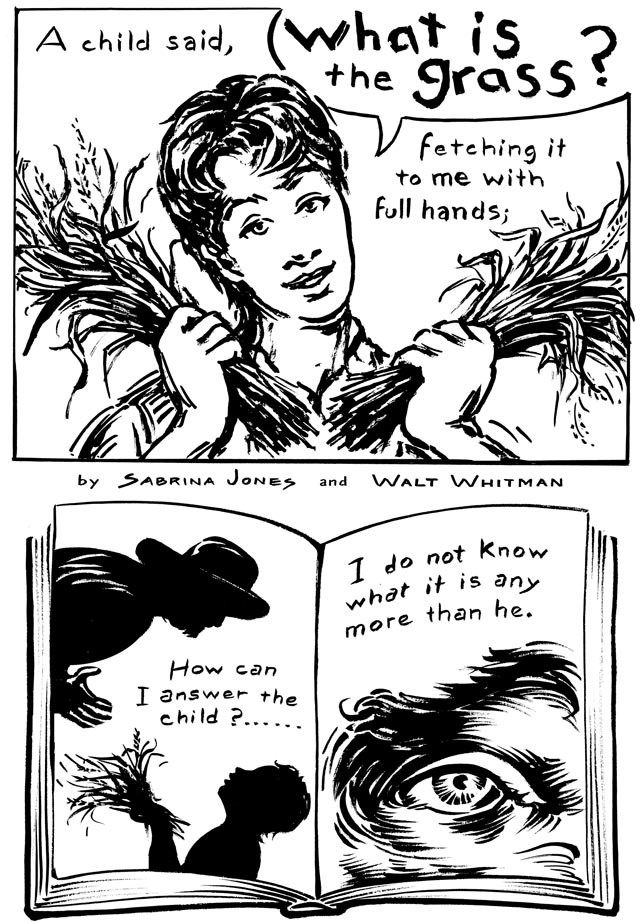

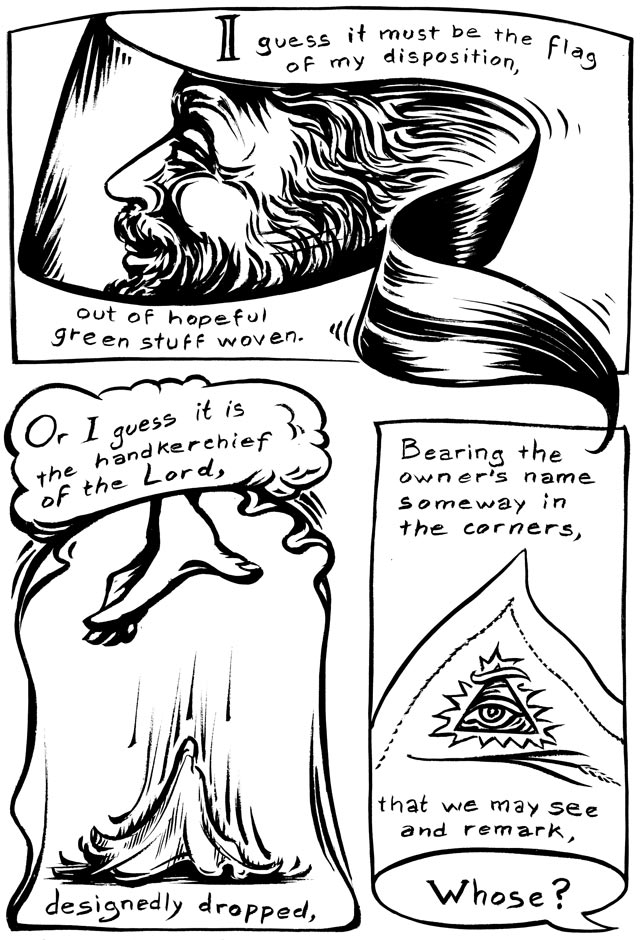

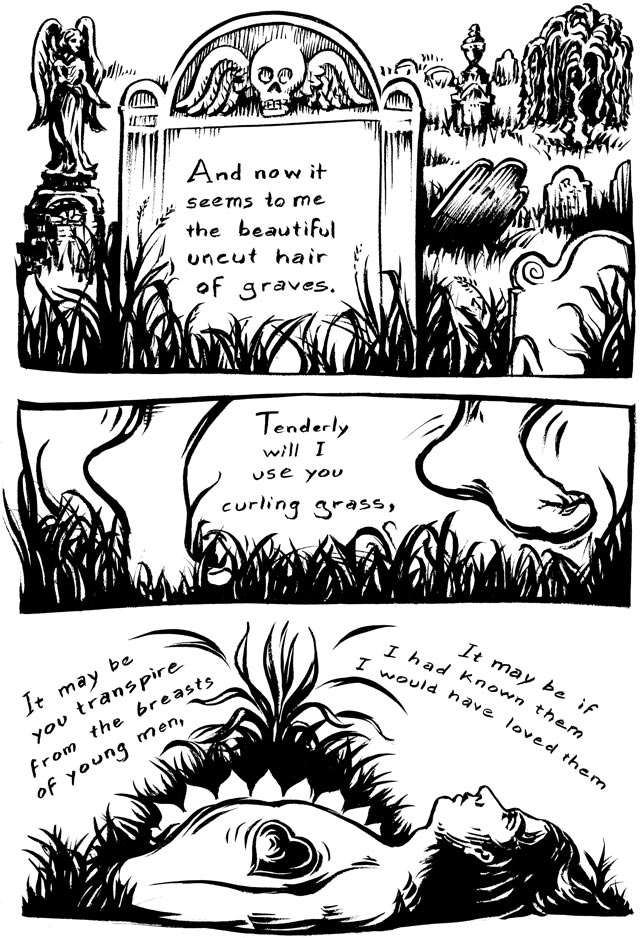

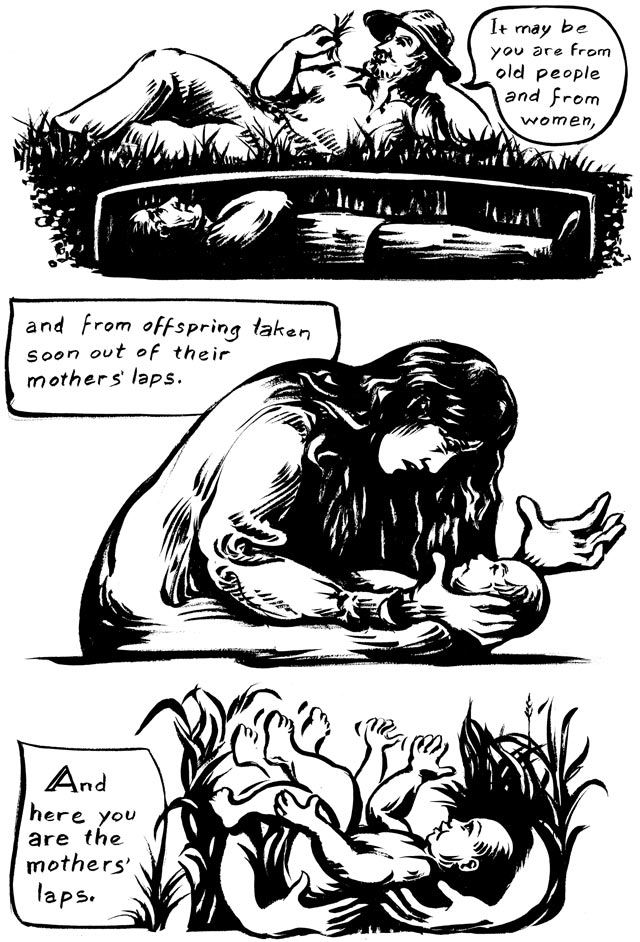

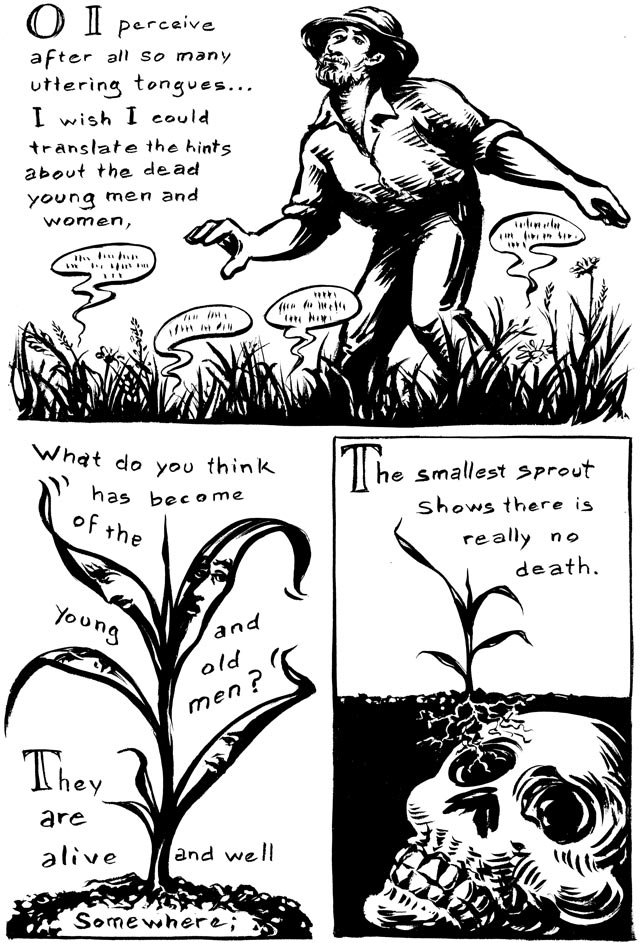

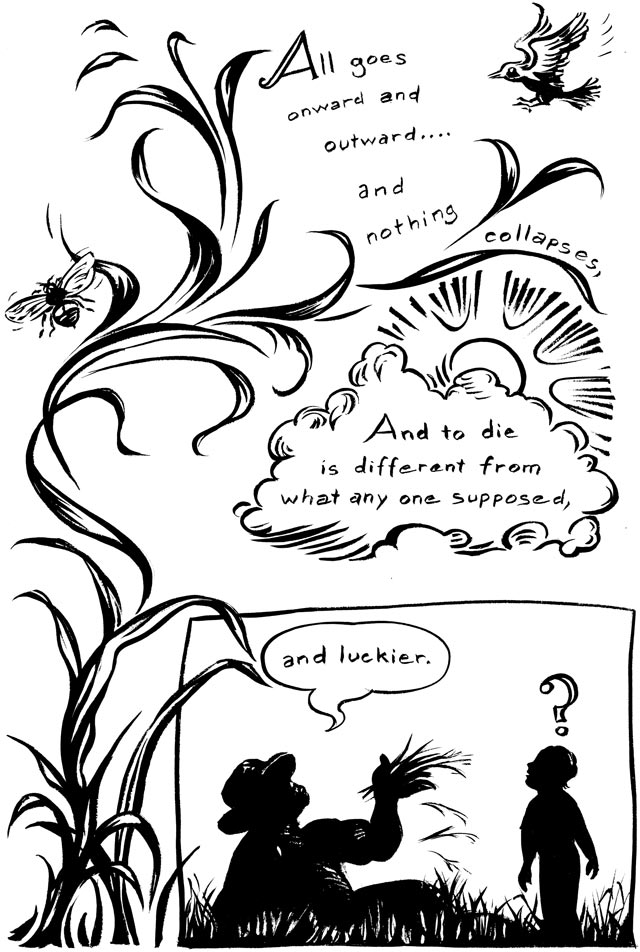

In the accompanying comic, artist Sabrina Jones gives us a glimpse of Whitman’s visionary sensibility. More of her interpretation is on display in the comic anthology Bohemians.#.

Paul Buhle co-edited Bohemians (2014) and has been a sentimental admirer of Horace Traubel as well as Walt Whitman most of his adult life.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.