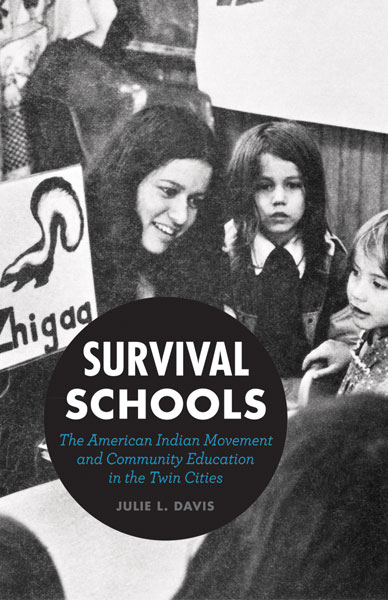

In her 2013 book, Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities, Julie L. Davis, offers the first history of two alternative schools for American Indian children, founded by AIM in the Twin Cities. Based on her 2004 doctoral dissertation, Davis describes how these schools revitalized Native culture and community from 1972 until anti-Indian forces directly or indirectly led to their demise.

Proving what the “Eight Year Study” demonstrated about the efficacy of alternative education, her interviews of graduates show how the survival schools created a slew of activists and innovative change agents who are still on the front lines today. Both schools were remarkably successful in helping the traditional cultural values of Indigenous people survive, but they also addressed such topics as peace studies, solar electricity, diversity, complementarity, gardening and fishing, which relate to the physical survival of our species.

Too few know about the survival schools – as too few know about how the eight-year study of 30 secondary schools proved status-quo approaches for teaching and assessment are unnecessary, or worse – or as too few know about the social change work of Helen Keller as a socialist, unionist, suffragist and antiwar activist. I submit that there is a similar hegemony at work that keeps universities from breaking away from an academic narcissism that supports specialized teaching of fragmented topics seldom guided by the recognition that we are facing a remarkable survival crises that calls for something else.

However, one university president, supported by her board of directors, is trying to change this problem. Katrina Rogers, Fielding Graduate University’s new president, wants to bring FGU’s vision for social and ecological justice, diversity and sustainability (SEJDS) to a more substantial level of implementation. Although FGU is a leader in doctoral education as it relates to its SEJDS achievements, like many other universities with similar vision statements and with programs or centers dedicated to such topics, it is also a victim of the status quo. It too suffers from shortfalls in its goals related to faculty and student collaboration, interdisciplinary curriculum, integrated and project-based coursework and dissertations that are about significant SEJDS issues. Rogers wants to start orienting all coursework to more specific SEJDS goals that would have everyone working toward creative and well-studied solutions to four of the most important challenges facing the world today:

1. The growing gap between the rich and poor and other related inequities

2. Climate change issues

3. Increasing scarcity of natural resources

4. Racial, religious and political conflict and violence

In other words, if passed by FGU’s various governing bodies, the entire university’s work in psychology, organizational development, infant and early childhood studies, social innovation, media and education will focus on stopping, preventing or otherwise mitigating problems relating to one or more of these interrelated global problems. In essence, it would become the first “survival university.”

Although this proposed vision focuses on global survival of life on the planet rather than survival of Indigenous ways of knowing and being in the world as the two Minnesota survival schools did, reliance on Indigenous world views may come to bear on the reorganized university’s curriculum. Referring to a book published in 1968, wherein two Belgian academics identified five different types of university models, Jean-Marie Boisson writes: “Their ideas can be reduced to the following extremely short synthesis: the Anglo-Saxon model provides the individual with a way to realise him- or herself through learning; in the German model learning serves the truth; the American model sees learning as being about human progress. In the two remaining models, the French and the Soviet, learning serves the needs of existing power structures.”

I do not know if this is still true or ever was, but as I write in my own book, Teaching Truly: A Curriculum to Indigenize Mainstream Education, Western education, whether at the kindergarten or the doctorate level, in most cases and regardless of vision statement rhetoric, serves more to sustain the four targeted problems in our world than it does to reverse them. Partnerships between Western and Indigenous worldview are something FGU’s Rogers understands as vital to her vision.

In referring to the “university of the future,” a Duke University article says, “For centuries, universities have made an unparalleled contribution to the expansion of knowledge and development of human potential. From health care to information technology to capital markets, university research has driven virtually every major innovation in the world, and universities have trained virtually every leader in every sector.” I agree with the importance of higher education emphasized here and believe that doctoral education has the ultimate influence in this regard. However, such university research has neither prevented nor solved the four targeted problems facing our world. More universities are now talking about their role in solving global problems, but they follow through on the fringes with add-on programs or underfunded centers. Robert Diamond, in his piece, “Why Colleges Are So Hard to Change,” offers reasons for this and writes:

Can institutions really change? Certainly. A number of colleges and universities have, under a unique combination of leadership and external pressures, undergone significant transformations. However, with few exceptions, where major innovation did occur, the institution faced the prospect either of taking direct action or of losing accreditation or of being forced to close. Innovation, in almost all of these instances, was a matter of survival.

Diamond refers not to survival of life on earth, but rather to the economic existence of an educational enterprise. The differences in motivation and policy between the two survival goals have overlaps, but remain huge. Such economic priorities call for a different kind of innovation that too often remains trapped in consumer-oriented trends or technological priorities. They tend to lead to specialization, and to avoid the authentic interdisciplinary work and relational dimensions that are necessary for individual and collective transformation. Furthermore, the paradigms of Western education’s “expert” model are hard to break. Academics, according to Alasdair C. MacIntyre, “are conditioned to become respectful guardians of the disciplinary status quo, sometimes disguising this from themselves by an enthusiasm for those interdisciplinary projects that present no threat to that status quo.”

Diamond continues articulating such concerns:

Unfortunately, at most institutions, any attempt to implement a major academic innovation has been perceived by a majority of faculty as a temporary discomfort that will simply vanish if they stay the course and do nothing. Reinforcing this behavior pattern is the fact that there are rarely any serious consequences for behaving in this manner.

FGU may well prove the exception to this. With support of faculty, staff, students, the president, the provost, the faculty senate and the board of directors, in light of its foundational goals in support of doing things differently and for the right reasons, the new vision has a chance. I believe it will require breaking the US paradigm of syllabus-driven course content that is separate from praxis. It will have to emphasize dissertation work from the beginning, as do many internationally based doctoral programs. It will require authentic, collaborative narrative assessment like that used by Alverno Women’s College.

In spite of competitive market challenges and reduced tuition dollars, success depends on a legitimate priority focus on the four targeted world problems. Finally, I believe it can only work with a collaborative, cross-discipline engagement among all stakeholders, colleges and curricula. Even with FGU’s history of boundary breaking, it will still be a challenge to come up with curriculum, assessments and teaching/learning strategies that will allow FGU to be the first university to entirely devote itself to doctoral studies across colleges that all focus on what most people agree are four of the world’s greatest challenges.

In his essay, “The End of Education: The Fragmentation of the American University” (2007), MacIntyre writes:

There are of course different ways in which such a curriculum might be implemented. And it would be important for it to focus on a limited number of problem areas or texts or historical episodes in the contributing disciplines, so that each problem, each text, each episode could be studied in some depth. Superficiality should be as unacceptable to the educated generalist as it is to the specialist. And a sense of complexity is perhaps even more important for generalists than for specialists, if generalists are to understand the difficulty of formulating and confronting the questions to which this curriculum will introduce them.

If Rogers’ new vision takes hold and faculty can implement a model of education that is in sync with it, she may be able to achieve the kind of depth and meaningfulness that MacIntyre intends – and FGU may become an international model for many more universities. How wonderful if the highest levels of education actually focused fully on bringing our world back into balance before it is too late.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $24,000 by the end of today. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.